By Tidiane Zalle (Tiipaalga) with support from Aida Zare and Femke van Woesik

This blog is part of a dossier on locally-led adaptation, featuring insights and lessons from the Reversing the Flow (RtF) program. RtF empowers communities in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan to build climate resilience through direct funding and a community-driven, landscape approach.

The Ziga Dam, located in Burkina Faso’s Central Plateau region, is a vital source of drinking water for the capital Ouagadougou, about fifty kilometers away. While essential for the capital’s water supply, its construction and operation have created lasting socioeconomic and environmental challenges for nearby communities. The reservoir’s filling submerged large tracts of fertile farmland, displacing residents and destroying their main sources of income. This has increased pressure on the remaining land, sparking conflicts and driving deforestation and encroachment into protected forests as people seek new areas to farm.

To safeguard water quality, strict restrictions were introduced on activities upstream and around the dam. These measures, though necessary, have further constrained local livelihoods based on agriculture, livestock, and artisanal fishing.

It is within this context that tiipaalga launched the Project to Support the Development of Community Water Management and Adaptation Initiatives in the Ziga Dam Basin under the RtF program. For the first time, Tiipaalga used a fully participatory baseline approach, shifting from collecting data about communities to co-creating knowledge with them. Conducted in six villages, the baseline was led by the communities themselves, with Tiipaalga facilitating the process. This ensured the assessment reflected local realities, strengthened community capacity, and provided a solid foundation for the project’s next steps.

Community-Led Baseline Methodology

For the community baseline assessment, tiipaalga used the Participatory Active Research Method (PARM), known in French as MARP. This method differs from traditional research approaches because it places communities at the center of identifying problems and finding solutions, while facilitators take an “optimal ignorance” stance: guiding without imposing. Local knowledge and community experience are the main sources of information.

Five participatory tools were used:

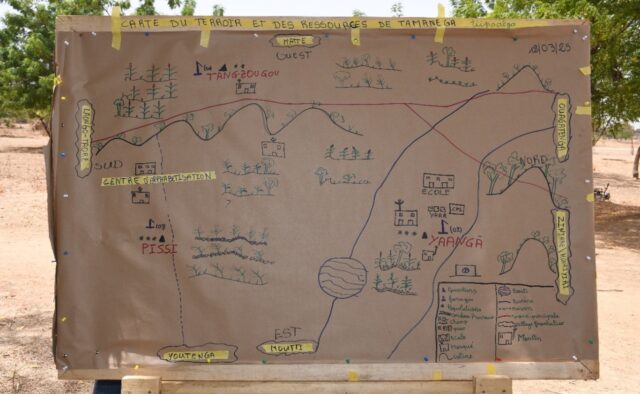

- Territory and resources mapping – a visual map created with the community to show natural resources, infrastructure, land use, and practices. Villages, roads, and key features were drawn on a large sheet during a plenary session.

- Historical profile – recorded major past climatic events, their impacts, and local adaptation strategies.

- Venn diagram – identified key actors (organizations, services, projects), their roles, influence, and relationships to improve coordination and avoid duplication.

- Vulnerability analysis – listed main constraints in each area and identified the groups most affected.

- Solutions analysis – involved a group brainstorming session to prioritize practical, relevant, and sustainable actions to address the identified challenges.

Before applying the PARM approach, Tiipaalga organized information sessions in each community to present the project, explain the process, and prepare participants for the assessments. The use of the five tools then took place over three days per village, with schedules adapted to local needs. For example, since the activities coincided with Lent (Christian period of fasting, prayer, and penance leading up to Easter), communities themselves decided the most suitable dates and session times.

This approach encouraged strong and inclusive participation. In total, 1,226 people took part, including 959 women. Prior to the baseline work, community members held awareness sessions in their villages to ensure everyone could participate. They stressed the importance of involving all groups (women, men, youth, traditional leaders, and internally displaced persons) so that every voice was represented. No specific gender targets were set at the start, but participation turned out to be highly inclusive.

Main Results

- Resources identified: The territory mapping identified the main natural and social resources in the area. Communities reported the presence of waterways, farmland, forests (village, sacred, and classified), and hills. Most villages also have a market, sometimes a vaccination park, a micro-dam, a mosque, a church, boreholes, connecting roads, and mobile network coverage.

- Significant climatic events identified: The most common climatic events are droughts, floods, and extreme temperatures. Other issues mentioned include strong winds, pest attacks, limited access to drinking water, and the impact of the Ziga Dam itself.

Communities attributed these events to deforestation, land degradation, climate change (irregular rainfall and heavy storms), and dam silting, which causes flooding. Their explanations show a clear, systemic understanding of environmental and climate challenges. - Vulnerabilities identified: The analysis revealed interlinked vulnerabilities affecting communities around the Ziga Dam:

- Water-related: 1) Limited access to safe drinking water despite proximity to the dam, due to insufficient infrastructure. 2) Shortage of water for agriculture and livestock, reducing production, income, and food security.

- Environmental: 1) Land degradation from erosion, overuse, and poor practices, leading to reduced soil fertility and yields. 2) Deforestation caused by fuelwood collection, farm expansion, and informal logging, leading to biodiversity loss, erosion, and reduced access to non-timber forest products.

- Infrastructure and economic: 1) Poor road conditions limiting market access, mobility, education, and health services. 2) Lack of support for income-generating activities (training, finance, market access), keeping communities in economic insecurity. 3) Few employment opportunities for youth and women, causing rural exodus and limited economic empowerment.

- Community-identified solutions: The communities proposed practical, multi-sectoral solutions to strengthen resilience: 1) Capacity building through training on sustainable land use, forest management, and agricultural production. 2) Material and infrastructure support, such as seeds, tools, boreholes, fencing for gardens and forests, bridges, and road repairs. 3) Improved access to services, including microfinance institutions.

From Baseline to Action

The baseline was not an end in itself but a starting point for collective action, feeding directly into community-led planning and decision-making structures. The information gathered during the baseline was documented directly on the participatory tools: territory maps, vulnerability tables, and solution matrices drawn on large sheets of craft paper. All materials remained with the communities to ensure transparency and ownership. The results now serve as a common reference for decision-making: any change to the agreed priorities must be validated collectively in village assemblies, with the documentation acting as proof of consensus. For reporting under the RtF program, Tiipaalga compiled a detailed baseline report and video on the approach.

The baseline went beyond identifying visible problems by helping communities analyze their root causes and the groups most affected. Based on this, they proposed practical adaptation strategies, all captured in a solutions table. Although external actors were not directly involved in the baseline, communities mapped those operating in the wider Ziga Basin to plan future coordination.

The next step is to establish village and municipal steering committees. Village committees of 11–21 members (representing neighborhoods, women (at least 40%), youth, and traditional authorities) will refine the proposed measures by assessing technical and financial feasibility. They will form subcommittees focusing on climate resilience, water management, and sustainable natural resource use. At the municipal level, a steering committee chaired by the prefect and including representatives from each village, local services, Tiipaalga, and the Local Water Committee (CLE) will oversee decisions and coordinate implementation.

The communities’ vulnerability and solution tables will guide these committees in developing detailed action plans. The village committees will define sub-actions, identify resources, and specify implementation details: for instance, whether a borehole should include a solar pump or irrigation system. Steering committees will consolidate village plans, promote synergies, and optimize budgets before approving funding. Each village will open an account with a microfinance institution, where approved funds will be transferred once regranting begins.

Why a Participatory Baseline Matters

Although tiipaalga has always prioritized community involvement, the program has, in the past, mainly used more traditional methodologies for its baseline studies, including more “classic” socioeconomic studies: sampling, individual interviews (survey through a questionnaire) with potential beneficiaries, semi-structured interviews, focus groups, direct observations, forest inventories (if relevant), and surveys of decentralized government services for aggregated data (e.g., agricultural yields).This is the first time tiipaalga has used the active method of participatory to conduct a baseline. This approach was placed at the heart of the baseline study. This methodology allows for a shift from a model where information is collected from communities to a process where data is generated with them:

“Before, it was the president of the Village Development Committee (CVD in French) and the women’s leader who were invited to workshops in town to voice the communities’ grievances. But tiipaalga’s approach allows everyone (young people, women, and the elderly) to have a voice. We ourselves prioritized our needs. Before, projects would come and say “we’re going to do this for you” without even taking their opinions. They accepted because they are in a situation of need. tiipaalga’s approach is different because it involved the community.” (Moanega, President of the Women)

This approach strengthens community ownership of the results while capitalizing on tiipaalga’s experience in dialogue and involvement with local communities. It reflects an ongoing commitment to deeper collaboration.

For tiipaalga, adopting a community baseline assessment offers several advantages:

- Better understanding of vulnerabilities: by placing communities at the center, the assessment captures vulnerabilities from the perspective of those who experience them, leading to a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the challenges. The data is enriched by experiential knowledge.

“We are feeling moved because this is the first time that opportunity and freedom are given to us to express ourselves at length about the situations we are experiencing and to propose solutions to our problems ourselves” (Youth from Nouhoutenga)

- Holistic approach and consensus: the community baseline assessment casts a wide net, covering a broader range of information and perceptions. This promotes greater consensus on intervention priorities, as they are identified collectively and not imposed from outside. This naturally strengthens community support for proposed solutions.

“The difference with other approaches is that when there was a project, we called two people to the town hall to represent the community. This could cause problems because it didn’t please some people and created problems of ownership of the projects because some people might not identify themselves with the interventions or say that they were not aware.” (Moanega, President of the Women)

- Transparency and relevance: Active participation ensures that the information collected is perceived as more legitimate and relevant by the communities themselves, which is crucial for the success and sustainability of projects.

Lessons learned from baseline study by tiipaalga

One of the major learnings is the shift in perceptions about tiipaalga’s approach to the program. Initially, based on previous conclusive experience, tiipaalga’s approach was peasant family-centered, with the idea that each family would submit a microproject for funding in the framework of the RTF program. This is the case, for example, of protection projects (protected plots) which have shown that the family approach can often give better results compared to the community approach. However, the baseline assessment revealed that beneficiary communities work better with a community approach for this type of intervention (climate problems, including drought, flooding, land degradation, etc., are rarely individual challenges). As an example, the community of an intervention village organized itself to advocate with an entrepreneur to rehabilitate their main access road. This is a perfect illustration of collective dynamics. It demonstrates a capacity for self-organization, mobilization, and collective action that goes beyond the family framework.

Tiipaalga’s lesson is that an approach that is too focused on the family can be a source of tension within these communities benefiting from the project and can foster the establishment of selfishness. It is a recognition that a family approach in a context where resilience often relies on solidarity and collective action can be counterproductive and harm the social tissue.

Furthermore, the shift from a family-centered to a community-based approach within the RTF program is evidence of the flexibility of the approach adopted. This is a powerful reminder that the best development methodologies are not fixed models, but rather adaptable approaches that draw their strength from listening to local realities. It is the art of accepting that the most relevant solution may be one that was not initially considered. This flexibility is necessary when doing things locally led.