By Nancy Kadenyi, Molu Tepo, Ibrahim Kabelo, Sahara Ahmed, Hosea Kandagor, Diramu Galgalo, Theophilus Kioko, and Femke van Woesik

This blog is part of a dossier on locally-led adaptation, featuring insights and lessons from the Reversing the Flow (RtF) program. RtF empowers communities in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan to build climate resilience through direct funding and a community-driven, landscape approach.

In Isiolo County, Kenya, one of the most powerful tools for locally led adaptation is also one of the oldest: the community baraza. A baraza is an open public meeting where everyone in the community, elders, women, men, youth, people with disabilities, can raise concerns, propose solutions, and make decisions together. Long used by chiefs and administrators, the format has in recent years been overshadowed by modern consultation methods. Yet for communities like Merti, barazas are proving to be a simple, inclusive, and cost-effective way of putting decision-making back in local hands.

When the RtF hub MID-P launched the “Community-Led Actions on Resilience and Climate Change Adaptation (CLEAR)” project, community members themselves asked for barazas to be at the heart of the process. They wanted a space where everyone could speak, not just selected committees. In their words, climate adaptation cannot be left to a few: it must be carried by all.

A journey to Merti

It was a wet April morning in Isiolo, the kind that turns red dust into sticky clay. The rain had pounded all night, yet our mission to reach Merti for a week-long community engagement under the RtF could not wait. We knew the rain could make travel somehow tricky, but we hadn’t expected just how challenging it would get. The mighty brown river Ewaso Ng’iro roaring its loudest at Gotu Bridge, the volumes are quite high, signalling a muddy, tough road ahead, with some villages like Basa automatically not reachable.

As we crossed a small bridge just after Bulesa town before Goda, our Land Cruiser sank deep into a muddy pothole. For three hours, tyres spun uselessly.

“In the mud, we found the true spirit of locally led adaptation: people closest to the challenge, leading the response.”

Ganna Raha the daily bus plying Isiolo Merti Route stopped to help us. Men and women jumped out, wading into the mud collecting twigs, branches and stones to remove our vehicle in the mud, helping the best way they knew. No speeches, no introductions, just a community instinctively solving a problem together. This reminded us that in the development work in such landscapes, it is not only strategy meetings and barazas but also being there with the people.

What is a Community Baraza and why was it preferred?

A community baraza is a traditional open public meeting, held at a greed community point bring people of the community (village or sub-location) together for open discussions, deliberations and decision-making. It originates from the government in colonial times where national and county administration -Chiefs and community leaders used to gather people for discussing government issues as well as community strategic decisions.

From the very first discussions, the communities preferred this approach as it is open to everyone, young, old, women, men, elderly, people with disabilities, name them and requested to be mainstreamed in the RtF Programme. As MIDP Hub, this approach presents an interesting opportunity to deliver the locally led principles.

It’s open to everyone, pastoralists, farmers, women, elders, youth, not just those on committees. This inclusivity is what makes it such a potent tool for locally led adaptation.

Barazas in Action: The Merti Case Study

From April 22–26, 2025, we engaged with the Merti community to better understand their priorities and challenges. Residents spoke of the Ewaso Ng’iro River shifting its course more frequently, causing floods that destroy homes, farmland, and livestock. They also raised concern about Prosopis, an invasive plant spreading quickly across rangelands and croplands, reducing productivity and even blocking waterways. Access to water remains another pressing issue, with limited infrastructure forcing people to walk long distances for both domestic and livestock needs. Finally, many women highlighted the growing problem of drug and substance abuse among young people, calling for stronger activism, education, and advocacy to prevent further harm to the community.

Breakthroughs of the Baraza Approach

In the current modern world, modern communication tools tend to dominate conversations and discussions, leading to an overlook on colonial time deeply rooted community engagement and participation method- the baraza. During colonial times, barazas (public meetings) served as a key open platform where the leaders and the community could meet to discuss issues, share ideas and make collective decisions face-to-face. Today in Merti with MID-P under the RtF program, this forgotten or rarely used methodology is gaining its way back to community engagement and participation for project planning and implementation.

The community engagement was conducted through the baraza approach (public meetings). With the barazas, there is extensive community engagement and involvement in collaborative decision-making when well-coordinated. It enhances inclusive community engagement and ownership of the selected initiatives. It is open to everyone in the community to join the discussion, rather than focusing on specific groups that might limit those not in the groups from joining the discussion. There is a big guarantee the interventions align with the community issues instead of addressing key groups’ interests and ideas. For example, the baraza was opened by the area chief there after the project concept was introduced for a joint understanding. After the introduction and setting the scene, due to cultural factors, men and women break into separate sessions to discuss their issues and possible solutions. The team came back to a joint session where each group presented their discussion and priorities for a merged voice discussion leading to a consensus-driven prioritization of needs and actions.

As engaging and inclusive the baraza approach is, it is not without downfalls. For example, the predominance of vocal individuals may lead to the marginalization of minority voices. What can be done to ensure that everyone in the baraza has an equal opportunity to share their perspectives? E.g. men have louder voices than women. Local politics, power dynamics and gender dynamics may influence decision-making processes as well as logistical challenges, such as timing and accessibility, may restrict participation. Despite the shortcomings, the baraza approach remains a strong tool for inclusive governance and engagement, especially when coupled with intentional facilitation that gives space to all voices.

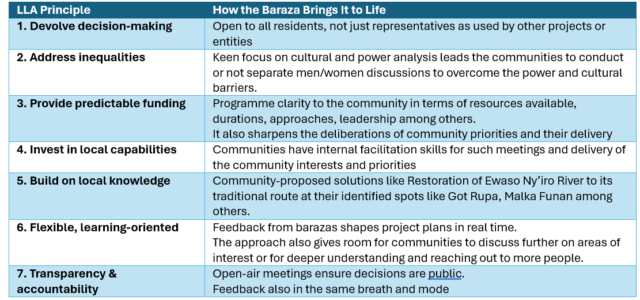

Why the baraza approach works- The 8 Locally Led Adaptation Principles Brought to Life

The baraza approach is more about transparency, accessibility and a platform of bringing everyone from the community to participate, not just giving a chance to those in specific committees or common interest groups. This makes the discussion reflect real, lived community issues rather than driving an agenda for selected groups. If well facilitated and coordinated, the baraza approach gives life to the Locally Led Principles and deepening:

- Extensive community engagement and participation

- Community collaborative decision-making and planning

- A strong community adoption and ownership of selected initiatives.

But it’s not without challenges

Like any participatory process, barazas are not perfect. Some of the drawbacks include:

- Dominance of vocal individuals, where Minority voices may be drowned out. This calls upon the facilitator and the coordinators to have intentional facilitation, for example, to invite the quiet voices to speak out, breaking into smaller groups, the way the discussion in Merti went, to give room for diverse opinions.

- Gender dynamics depending on the culture hindering others from speaking out, e.g men speaking more and women are hesitant to speak out to contribute to the joint sessions and decision-making.

- If not carefully coordinated, local politics and power can influence the decision-making process.

- Logistics and location must be carefully thought of, otherwise there will be limited participation e.g. due to time and distance.

From the baraza discussion in Mert with MID-P, several takeaways emerged.

- Community mobilization and participatory governance are game changers in community participation and engagement.

- Having the community at the center of decision-making and planning drives the ownership of initiatives and their long-term sustainability.

- The cost-saving baraza approach during the inception phase of a project provides a smart choice for early community engagement and buy-in.

The Baraza approach remains a powerful and people-centered tool and approach for inclusive governance and community active engagement and interaction. When well facilitated with care and inclusiveness, it is more than just a chief’s meeting but a space where voices converge, share ideas, merging priorities and foster growth of ownership. In this era of emails, webinars, online surveys, WhatsApp, etc. it is also a time to remember that sometimes the most effective and interactive tool for engagement is when in the past we used to seat down in circles, under the sun or under a tree, having talks and discussions together.

This leaves us with this food for thought when everyone is talking about climate resilience and locally led adaptation: How can community-based governance models strengthen climate resilience and locally led adaptation? And what is the effectiveness of approaches like Baraza in locally led adaptation?

Call to Action: Could this be the missing link between global climate/ finance and real change on the ground?

Billions are pledged for climate action, yet little trickles down to the people most affected. The baraza could be the connective tissue, turning distant financial commitments into tangible community-owned action plans. By linking grassroots priorities directly to funding streams, we close the gap between promise and practice. Imagine climate and biodiversity finance flowing not to consultant-heavy reports, but to initiatives born under the shade of a tree in Merti. That is where resilience takes root.