By Anna Smits

March 19, 2015

Image: WikiCommons

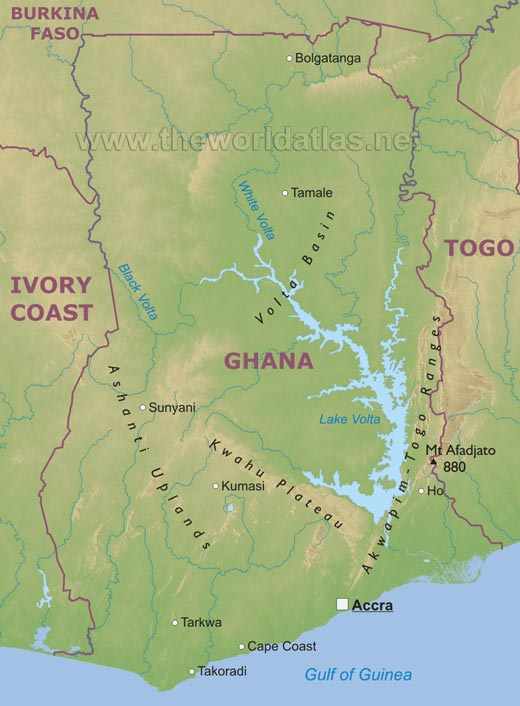

“Climate change is the time that the moon and the sun come together and there is darkness” a lady in a small village in Ghana told me a while ago. A farmer from that same village pointed out to me that the changes they have experienced in temperature and rainfalls represent climate change and that they should stop the excessive felling of trees in order to reverse it. Since this village in the Akwapim-Togo mountain ranges of Ghana covers only 300 metres of a kilometres long dust road, I was wondering about the locals’ subjects of daily conversations. It seemed almost impossible to me that the two had never exchanged a word. Had it never come up in all those years?: “Hey neighbour, gotta love the weather today, finally rain for our crops!” “Yeah it is not as in the olden days” “Indeed, people should really stop felling trees to get those times back” “What do you mean?” “Well you know, climate change…” “Climate change, isn’t that the moon and the sun coming together and creating darkness?” “No silly (oke, a Ghanaian would never call someone silly like that), it is the changes in weather over a long period!” And if they had not had my imaginary conversation, what of several trainings on environmental issues such as climate change and degradation a village representative had enthusiastically told me about? The one that the traditional leader picked him to go to and that he had shared in a community gathering?

The more villages I visited, the more the unequal distribution of knowledge amazed me. Explanations of climate change went from including “It’s all from God” to “I know very well, photosynthesis, when it takes place, it helps us to get more rains”. It did not stop at climate change, when discussing farming practices both “weedicide (weedkiller) drains into the ground and makes it fertile” and “I don’t use chemicals because it makes the soil wear down” passed in review. Where is this coming from? The goal here is not to filter out what definitions are right and wrong, it is simply to wonder how they can be so far apart. What causes the perception of the solar eclipse lady to be so different from that of the farming townsman? It is an area where several educational activities, tree planting exercises, radio programs and other projects to make locals aware off and let them participate in dealing with environmental threats have taken place. Thereby, stemming from ancient customs, each village has regular ‘community gatherings’ lead by the traditional authority with the chief at the head. At least there is no complete lack of knowledge sharing opportunities…

Does it have something to do with Francis Bacons’ ‘Knowledge itself is power’? When bringing a project to a community, all initial contact has to go through the traditional authority. Sometimes even with all the trimmings such as a bottle of schnapps and a ceremony. The chief then appoints the one who will be working with you, or who can go to your training. Does he indirectly also decides who gets the knowledge? On the other hand, one of the main goals of the community gatherings is to pass on information, as the chief forms the link between the villagers and the local government. Is it knowledge’s opposite , ignorance, then? One Queen Mother (head of the women in a village) stated that “ignorance leads people to destruction”. She said that her people have to be told over and over again about the environmental issues in their surroundings: “In the Weto Range (local name for Akwapim-Togo ranges) we are not really sure of what is good for us. All that we know is what will go into our mouth, what we live on daily, that is all. What will be sustainable, what can keep us day to day and leave some for future generations to come, that is not our idea”. But if we have to believe NGO’s, local government and several traditional leaders themselves, this ‘telling over and over again’ is being done in the gatherings. Of course there is also the possibility that people do not receive the knowledge because they simply don’t attend any gatherings. But how far can that really keep people in the unknown in a small environment where social control is strong and where safety nets merely exist of fellow community members?

Community gathering in a village in the Akwapim-Togo ranges, with left the traditional authority (own image)

Zooming out, findings about unequal knowledge distribution on environmental issues in little villages in Ghana are nothing new under the sun. In a book on information communication technologies it reads that in various African countries one of the biggest obstacles in developing ‘good governance’ and participatory democracy is the passing and distribution of information. This brings us back to ‘Knowledge is power’ as it goes on to elaborate on how knowledge can be used to get authority over those who know less and that this authority can either be used to dominate or to serve communities. Knowledge sharing for the purpose of development is promoted extensively in academic writing and development projects and reports. A lot can be found on that we should share, also at the local level, within rural communities for example, but less can be found on how that is working out. For the communities in the Akwapim-Togo ranges, it is not working out equally as good for everyone. Pointing the finger at the traditional authority would be too easy, especially because I have met several leaders who seemed very passionate about the development of their community. Unfortunately, I cannot end this narrative with satisfactory conclusions. Presumably, a combination of power, ignorance and disinterest guides you in the right direction when wondering about the distance between the perceptions of people who are in fact so close. Even if we do not exactly know the underlying processes, that does not mean it should not be taken into account when following the popular call for knowledge sharing, education and awareness raising on environmental issues. It is a good thing when a village representative gets invited for a training, but, despite his best intentions, is there a follow-up on how the rest of the village shares in that excitement? And more importantly, is it really the whole village that gets to know?

More information:

Craig van Slyke (2008): Information Communication Technologies: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; INFORMATION SCIENCE REFERENCE

The Akwapim-Togo Ranges in the Volta Region of Ghana (Image: WikiCommons)