By Iqra Khan, Arpan Mondal

Despite innumerable interventions by the state and civil society, the shadow of paradox lingers on the state of Jharkhand in India. The paradox of owning abundant natural resources and yet being deprived of basic amenities required for living a dignified life. The recent Multidimensional Poverty Index Report 2021 released by Niti Ayog reaffirms this paradox as 42.16% of the Jharkhand population is multi-dimensionally poor, India’s second most impoverished state. Jharkhand is associated with spatial poverty, where Adivasi communities live in the forest fringe areas far away from the city. Others restrict it to mining areas displacing 6.5 million people in Jharkhand, constituting 40% of India’s mineral wealth (Indian People’s Tribunal on Environment and Human Rights). The state is battling various challenges of underdevelopment, malnutrition, low literacy levels, unemployment, distress migration, and high incidence of poverty due to weak institutional mechanisms and lack of good governance. As a result of the Indian Developmnet Action organicastion: PRADAN’s engagements, collective efforts are underway to engage systematically to bring the poor and vulnerable out of the cycle of poverty and vulnerability. This blog shares the community, the processes adopted to sustain the efforts, and insights drawn.

Steps were undertaken to support ultra-poor families of Torpa block through the system’s approach. The process involved the orientation of community members on understanding contextual poverty and collectively defining the indicators of ultra-poor at various forums such as women collectives, tola, and Gram Sabha. A wealth ranking tool was adopted to identify these ultra-poor families. The identification process was done through checks and verification by community-led institutions, including women collectives and self-governance forums like Tola Sabha.

The indicators listed by the community to identify ultra-poor included:

(a) Families/individuals struggling to sustain themselves for only 4-5 months of the year on available rations.

(b) Landless families

(c) Families ostracized by the community

(d) Woman-headed family with dependents and single woman

(e) Distress migrant family

(f) Mentally or physically disabled and

(g) Orphans

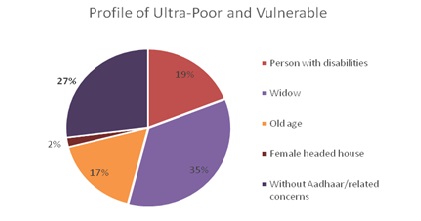

As a consequence, a total of 540 ultra-poor families/individuals were identified across ten panchayats in the Torpa block. A sample profile of 55 ultra-poor families is as follows:

Once the identification of such families at the Tola and Village Organization (VO) level, the ultra-poor list was shared and discussed in Gram Sabha. A copy of it was also provided to the panchayat so that they could be linked with various social welfare schemes by prioritizing them among others.

The approach adopted by PRADAN and Gram Sabha included a participatory and community-centered approach. A needs assessment and resource mapping was conducted to understand ultra-poor households’ specific needs and challenges.

The ultra-poor were identified and bracketed into four categories based on the severity of their conditions: A, B, C, and D:

- Requires immediate attention

- High level of need

- Moderate level of need

- Relatively better off but still requires support

Consequently, Gram Sabha and women collectives immediately supported category ‘A & B’ ultra-poor families by providing ration, clothes, and vulnerability reduction fund (VRF). A few panchayats supported the ultra-poor, distributing quilts and rations to such families. Based on needs assessment, many ultra-poor families/individuals were deprived of welfare scheme benefits. About 270 such families were supported to apply for welfare schemes, of which 40% have been realized. Most welfare schemes include widow pension, old age pension, National Family Benefit Scheme (NFBS,) and other prerequisites to avail of these schemes such as Aadhaar, birth and death certificate, and affidavit.

Apart from this, PRADAN is demonstrating two livelihood models to supplement the incomes of the ultra-poor based on resource mapping. One is backyard poultry (BYP), and another is the cultivation of elephant foot yam. Reasons to opt for backyard poultry:

- It only requires a little land.

- It is a less resource-intensive activity. This activity was adopted by families with few members, single women, and intellectually or physically disabled families.

- BYP can feed itself.

- Their maintenance is comparatively easy.

- Pashu Sakhi and Paravet are available in these panchayats and monitor this activity with regular guidance along with the women’s collective.

- Vaccinating and deworming chickens costs about Rs 21 per year, which most ultra-poor families can afford.

- Good profit can be earned with less expenditure and less care.

- Consumption of eggs and meat by these families is a significant source of nutrition.

- Due to the high demand for BYP in the local market, it is easy to sell native-breed chickens.

A total of 33 ultra-poor families were supported in March 2023 by providing them with BYP shed materials, feeders, drinkers, and three adult hens. The cost of one unit came out to be Rs1800 per family. The chickens of these indigenous breeds were procured locally from the nearby villages to ensure they did not die due to adaptation, environmental change, and stress. About 10% of the distributed chickens have died due to extreme heat and other reasons, and 60% are laying eggs. Since these hens are laying eggs for the first time, they give fewer eggs. On average, 7-8 eggs have been laid by a hen in the first cycle, which will eventually increase to 12-15 eggs in subsequent cycles. The families have yet to consume eggs and chickens to increase their herd size, barring a few exceptions. Until now, staff members have observed 20% of mortality. Depending on the current situation, there is a strong possibility of making an average profit of 12000 to 14000 by selling the chicken and eggs in a year. Reasons to opt for elephant foot yam cultivation are the following:

- Less resource and labor-intensive.

- Contextually aligned livelihood activity.

- It requires less water; hence, rainwater is sufficient for elephant foot yam cultivation.

- It doesn’t require additional fertilizers and pesticides. Good yield can also be harvested by using cow dung alone.

- Technical support can be extended to these families by progressive farmers of their community.

- Good profit can be earned with less expenditure and less care.

- It is also a good source of nutrition.

To diversify their income sources, 100 ultra-poor families were supported with 5 kg of yam corms. The cost incurred per family was Rs 200. The process involved the agriculture staff training of ultra-poor families in each panchayat, along with Krishi samiti members. This event was followed by the distribution of 5kg of yam corms by the elected representatives at the panchayat Bhavan on May 26, 2023. Nearly 95% of elephant foot yam corms have sprouted, and one is hopeful they will be ready to harvest in the next five months. This activity will support the family with an additional income of Rs 5500-6000, which can be multiplied by storing its seeds.

Insights:

- There are different faces of vulnerability layered with multiple disadvantages. Prominent among these are social and economic disadvantages, geographical limitations, political scenarios, and limited coping capacity coupled with insecurities. For instance, Rudan Devi (69), a widow, stays with her son, who is physically disabled, her daughter-in-law, and three grandsons. They belong to the service caste named Turi, known for basket weaving, and have no land. Importantly, neither Rudan Devi gets her entitled support of old age pension nor her physically challenged son gets his entitlement support for his disability.

- Some indicators in isolation have contributed to understanding the condition of the ultra-poor, while in other cases, a couple of factors together account for extreme poverty. Nirali Topno (68) lives with her husband (72) and a granddaughter (12) in a hamlet of Marcha village. Their daughter had to send the granddaughter as a helping hand to the aging couple. It led to the discontinuation of her studies. They own 1.5 acres of land, but due to physical inability, they have given their 1 acre of fertile land to neighbors from whom they get a portion of the produce. Only Nirali has access to an old-age pension, but not the husband.

- Social capital plays a crucial role in the lives of people experiencing poverty as they fare better than those lacking contacts or are neither part of women’s collectives nor take part in Tola and Gram Sabha. For instance, Renu Devi (33), a resident of Dao Toli, lives with her family of 4 members. The family molds iron on an occasional basis and works on the host community’s land as agricultural laborers. The couple sustains their family by rearing livestock and has access to welfare schemes like ration, livestock schemes, and credit facilities. She says that her family has benefited from being a part of a Self Help Group, and her neighbors ask them first if they must hire laborers.

- While the ultra-poor are primarily women, a significant vulnerability can result from the intersectionality of caste dynamics, social standing, and occupation. For instance, Kandan Lohra (80), a resident of Jagu village, is a single person who has coexisted with the Oraon community for ages. He doesn’t own any house and lives in a dilapidated one-room. He has no documents, hence neither a ration card nor a pension to sustain himself. He must be physically capable enough to do any work but molds iron as part of his traditional occupation. He has a daughter who went with someone to work in the tea gardens in another state and never came back.

- Adopting a lengthy process is sensitizing every local forum towards its most vulnerable and poor section of society. The community’s direct and indirect actions often impact those living on the periphery. Therefore, to help them access their rights & entitlements, one needs to sensitize the community towards their vulnerable and ultra-poor, build capacity of the ultra-poor, customize context suitable livelihood options, and create awareness around their rights.

- Amidst the engagement period, there is a realization that dedicated time and human resources are required to immerse oneself in this program of sensitizing and engaging with the ultra-poor.

- Identifying and assisting people experiencing poverty is a time-consuming and strenuous process, which requires ample patience and sound mental health of development practitioners. There were moments when those closely involved with the ultra-poor remained disturbed for some time, affecting their health.

- Particular Focus on the ultra-poor rather than the community as a whole will not effectively contribute to addressing extreme poverty, as push and pull factors of a market economy will expose a section of society to shocks and uncertainty at one point or another.

Challenges:

- Systematic barriers in the effort to realize the social security schemes

- As an Aadhaar is a prerequisite to avail any scheme benefit, 15% of the ultra-poor still need one owing to misinformation, inadequate enrolment facilities, update and retrieval, and technical biometric glitches.

- Initial resistance from ultra-poor families regarding the success of new livelihood activities.

- Elite capture of welfare schemes in Gram Sabha, Tola Sabha and Panchayats

Opportunities:

- Different institutions want to focus on people experiencing poverty and are interested in working in collaboration.

- The combination of BYP and Elephant foot yam farming has provided a diversified income source for the family, thereby reducing their dependence on a single income source.

- Increased access to nutritious food due to the cultivation of poultry products and elephant foot yams contributes to better health outcomes.

- The program’s initial results gave the family a sense of self-confidence and self-reliance.

- Gram Sabha has realized its responsibility to prioritize such ultra-poor families, further playing a role in strengthening local governance platforms.

PRADAN’s engagement with the ultra-poor and vulnerable is premised on the spirit of collectivism and driven by a rights-based approach. The existing deprivation due to the historical burden of marginalization has further exacerbated their inability to access their rights and entitlements, leaving them bereft of dignity and self-respect. While engaging with these disadvantaged groups to move out of the cycle of poverty is significant, it is equally necessary to sensitize the community. The community’s direct and indirect actions often impact those living on the periphery. Therefore, to help them access their rights & and entitlements, one needs to sensitize the community towards their vulnerable and ultra-poor, build capacity of the ultra-poor, customize context suitable livelihood options, and create awareness around their rights. These would be some of the ways to sustain the efforts of an organization like PRADAN to support the ultra-poor.