I am a 3rd year BSc International Land and Water Management student and have written this article as part of my assignments for the WUR Honours program. The idea of quantifying natural resources as capital assets has fascinated me because of both how potentially empowering or detrimental such a construct could be. I used this assignment as an opportunity to look at how such an approach was used in Belize to help policymakers create better development plans.

In 2016, UNESCO touted Belize’s new coastal zone plan as one of the most forward-thinking ocean management plans in the world (Source: UNESCO). The following article looks at how the use of natural capital accounting influenced the processes involved in the formulation of such a well-received natural resource management plan.

Assigning a financial value to nature is an example of the human need to quantify and operationalize abstract ideas into tangible facts; think of everything from happiness indices to social credit scores. Our habit of translating everything into a metric informs a lot of our actions and decisions as a society. While there are poignant arguments against doing the same with nature, we cannot discount the instances when such an approach has benefitted nature and, ultimately, humans.

A noteworthy example of ecosystem restoration in this context is the coastal conservation effort in Belize. Being home to the planet’s second longest reef system, close to 40% of the population depends on the coastal zone for livelihoods. Acknowledging the importance of these resources, the government first made an effort to protect the coastal zone through its Coastal Zone Management (CZM) Act in 1998. The act commissioned the Coastal Zone Management Authority and Institute (CZMAI) as the body responsible for planning conservation action to ensure long-term social, economic, and ecological sustainability.

Recognizing the need to work with multiple stakeholders at different levels, the CZMAI decided to outline a process to develop a national strategy to improve coastal management. From 1999 to 2004, the agency worked on a UNDP and GEF-funded project. The project had the purpose of providing decision-makers and relevant stakeholders with analytical, management, and technical capacities, decision-making and planning tools, and financial mechanisms and economic instruments for the long-term conservation of coastal and marine biodiversity. This project, however, ended with the realization that the lack of a sustainable financing strategy was the biggest limiting factor in what CZMAI could achieve. By the time the project concluded, financial bottlenecks led to considerable downsizing of the department’s activities. This operational hiccup also meant that newer development projects by different authorities were limited to the scope of their jurisdictions. Thus, depending on whether a zone is managed by the fisheries, forestry, or tourism department, the management approach would serve their respective priorities. Such incoherence in action creates inconsistency in regulations, leads to disjointed outcomes, and undermines the possibilities for any cumulative impact.

After a change of power in 2008, the new government reinstated the CZMAI. This time the authority was to partner with the Stanford-based Natural Capital project (NatCap) to develop a strong science-policy process to guide future coastal management. The NatCap project here was a technical collaborator who would assist in the creation of the science required to build a comprehensive plan. The team performed an assessment using their in-house InVEST(Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs) model to quantify and map natural capital stocks. This type of assessment seeks to value ecosystem resources and services in monetary terms depending on the value the direct or indirect value they bring to people. The results obtained are then corroborated with insights from stakeholder consultations. Doing so, helps contextualize the metrics with the vision local communities have for their environment and livelihood.

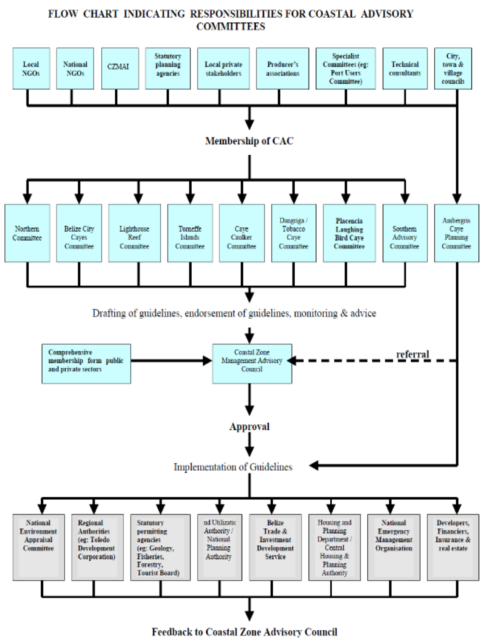

Stakeholder engagement in this context was done through the formation of regional Coastal Advisory Committees (CACs). Each region had a committee consisting of representatives from the municipality, NGOs, business owners, officials from different departments, and community members depending on the main economic activity of the area. There were also different levels of acceptance and participation across various places. Regions where people’s vocation was closely tied to coastal resources were much more eager to participate and contribute to making a plan beneficial to their livelihoods and environmental sustainability. In contrast, regions where people were less directly dependent on the coastal ecosystem—such as those where agriculture provided more jobs than tourism or fisheries—were more hesitant to partake with fears of possible regulations that would limit their activities. The strategy to deal with these doubts was for the CZMAI and other project promoters like the NatCap team to take an observational role in the CAC discussions (Fig. 1). Meaning the project developers would not actually lead the talk but rather let a rotation system allow different members to chair meetings, fostering a bottom-up approach. This would obviously take more time, but the CZMAI leadership believed that it would, first, allow most disagreements to be resolved through exhaustive dialogue. Second, it gives each stakeholder a sense of ownership over the plan, increasing their cooperation during execution.

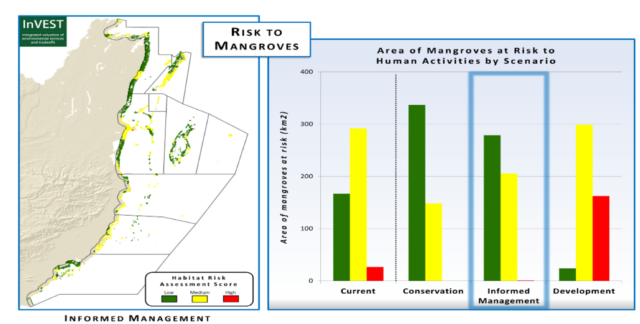

Following the completion of the NatCap assessment, the project modeled temporal scenarios to envision the long-term impact of different management strategies. In addition, the project developed a spatial zoning scheme at both national and local levels to designate areas where certain human activities may or may not take place in accordance with the selected scenario (Fig. 2). The three management scenarios were as follows:

- CONSERVATION: presents a vision of long-term ecosystem health through sustainable use and investment in conservation.

- INFORMED MANAGEMENT: blends strong conservation goals with current and future needs for coastal development and marine uses.

- DEVELOPMENT: prioritizes immediate development needs over long-term sustainable use and future benefits from nature.

These scenario-based projections would give decision-makers insight into how each approach would increase each zone’s economic and ecological value in the long term. Looking to strike a balance between economic benefit and long-term ecological sustainability, the informed management scenario was chosen to devise the plans and policies for coastal management.

The final Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) plan delivered by CZMAI in 2016 included directives for policies and operations across all government ministries to collectively impact the country’s natural resources. Provisions were put in place to ensure the plan kept evolving periodically with a review process based on the status of the natural capital stocks.

As a result of this extensive planning, Belize has seen more cohesive policies from different departments. A good example of this is the Blue Bond for Ocean Conservation initiative, a program that embedded blue carbon benefits from conservation efforts into fulfilling the country’s NDC commitments. In another success, UNESCO removed the Belize Barrier Reef System from its list of World Heritage Sites in danger in 2018, thanks to regulatory changes and protections from the plan. Looking at the complete picture, the benefits of taking a natural capital approach towards conservation can be summarised as follows:

- The valuation of ecosystem resources and services provides a unified data framework for cross-sector collaboration. Allowing decision makers to depend on a common data source to plan their actions, ultimately reducing the risk of policy fragmentation.

- Innovative funding mechanisms can be based on natural capital stocks to secure sustainable finance for conservation and management efforts.

- Standardized and replicable metrics allow for consistent tracking of ecosystem health. Facilitating continuous improvement of policies and management practices.

- It helps align economic growth with conservation goals to ensure regulations do not cannibalize the livelihoods of people dependent on the natural resources in question.

The use of natural capital accounting in developing the ICZM has undoubtedly helped Belize create an impactful process for decisions regarding the management of the country’s coastal resources. Being an evolving plan, there have been iterative updates to it since it was first accepted. The scientific process involved in the plan is replicable to a large extent in most other geographical zones, with some modifications to the methodology. Examples of this have been seen in other regions, such as Chile, Sri Lanka, and China, among others. The political will for such changes, however, is a very tricky issue. In Belize, where a major portion of the population and economy have a high dependence on coastal resources. The process of drafting and implementing a plan for integrated management has more public interest and political will compared to a nation with lower dependence on such resources. While Belize’s case offers great lessons in creating a science-backed policy framework, replicating its successes in other contexts will require adaptations to local socio-political realities.

REFERENCES:

UNESCO’s acknowledgement of Belize’s plan- https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1455

Belize ICZM plan- https://www.coastalzonebelize.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/BELIZE-Integrated-Coastal-Zone-Management-Plan.pdf

UNDP/GEF Belize project evaluation- https://www.gefieo.org/sites/default/files/documents/projects/tes/592-terminal-evaluation.pdf

Coastal planning in Belize: systems thinking and stakeholder engagement on a national scale- https://sustainabilityleadership.stanford.edu/sites/changeleadership/files/media/file/sust_case_study_-_natcap_belize_coastal_planning.pdf