posted by Frank van Steenbergen

October 22, 2012

It is fair to say that basin management has been the celebrity cause for integrated water management. In principle, basin management brings all hydrological process together. As such it is instrumental in finding a balance between different but highly inter-related interests in water use. Basin management is, for instance, the centrepiece of the much heralded (but less implemented) European Water Framework Directive.

But what are basins? And does it make sense to manage water resources at basin level?

Whereas there is much merit in managing water in an integrated way and look at the larger area, there are also a number of arguments not to ‘overdo’ basin management.

The first argument concerns the existential question: what constitutes a basin? Obviously a basin is defined by the drainage pattern in a landscape: water first converges in smaller streams and from small streams into larger streams till it all ends up in the estuary or delta of the larger river. This seems straightforward but there are a number of questions.

First, where does one begin and where does one end? A basin is like the Russian matryoshka doll. One opens one doll and there is a smaller doll inside. Same with the basin concept – every basin consists of smaller units that consists of smaller units: call them subbasins, catchments, subcatchments. So where would basin management focus on? Does one take the basin as a whole or does one zoom in at one of the smaller units?

First, where does one begin and where does one end? A basin is like the Russian matryoshka doll. One opens one doll and there is a smaller doll inside. Same with the basin concept – every basin consists of smaller units that consists of smaller units: call them subbasins, catchments, subcatchments. So where would basin management focus on? Does one take the basin as a whole or does one zoom in at one of the smaller units?

Some also suggest a movement in the other direction. This is the concept of ‘mega-watersheds’. The argument is that below a basin there is a larger picture of deep groundwater layers that often cross basin boundaries. In mega-watersheds one looks at this larger picture as well – at least to identify the main sources of (deep ground) water.

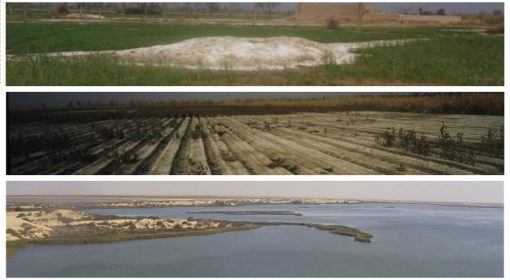

The second argument not to overdo basin management is that not everything in a basin relates to one another. In many cases basins may be just too big. Particularly when there are large desert parts of a basin, the linkage with other hydrological processes may be small. The same applies to areas ‘where there is no river’ and that depend mainly on groundwater.

Finally, in some areas basin boundaries hardly matter. This concerns the flat lands, often also home to the most productive farmland. In such plains water is easily diverted from one ‘basin’ to another. A small obstruction may already do. In many coastal plains, rivers are braiding and interconnect with one another and the basin idea becomes arbitrary.

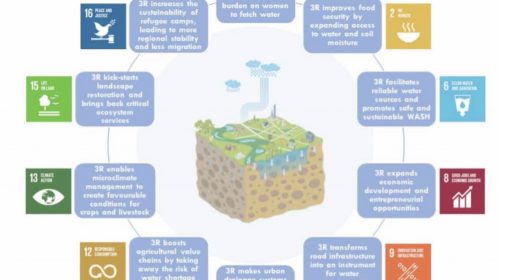

What seems a better– or at least complementary concept– to basin management is a focus on areas where there is intense hydrological interaction: where rivers feed adjacent aquifers and are being fed by them; or where there is intense pollution that can be reduced by river and wetland processes; or in a small catchment where good buffering of local water resources can cause a turn-around, with less sedimentation, more recharge and a changed micro-climate. Hence, rather than trying to manage the whole and partly elusive ‘basin’, it makes more sense to better understand these areas of intense interaction and how they can be best managed.

{jcomments on}