By Humayra (Community members) Md. Shirazul Islam, Md. Mehedi Hasan (Shuvo) , Kona (Uttaran) and Mst Jannatul Naim

This blog is part of a dossier on locally-led adaptation, featuring insights and lessons from the Reversing the Flow (RtF) program. RtF empowers communities in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan to build climate resilience through direct funding and a community-driven, landscape approach.

Background: When Disaster Reshaped a Landscape

The Hajrakhali community, situated along the Kholpetua River in Asasuni, Satkhira, the southeast of Bangldesh experienced a dramatic transformation after Cyclone Amphan in 2020. The storm surge broke through the embankment and flooded surrounding villages; the sudden cyclonic surge and flush flood carved a narrow channel beside Hajrakhali into a large canal over time. Which is now overflowing onto nearly 120 bighas (7,500 decimals) of low-lying land. Many houses were swept away or eroded, leaving Hajrakhali isolated as an island, cut off from the mainland.

At first, the canal was used as a shared fishing ground by everyone. But soon, outsiders with political influence leased it from absentee landowners who lived outside of the community, illegally excluding small landholders who lived in the community. Their plan: shrimp monoculture with saline water, a practice that would have devastated the freshwater system, destroyed fertile soils, and endangered drinking water and agriculture.

Worse, temporary fishing houses were set up, and with them came more outside-spoiled people with drug activities and local insecurities, further threatening community wellbeing.

Community Reflexive Action: Raising Their Voice Against Power

The people of Hajrakhali stood together and took collective action. They repeatedly submitted written and verbal complaints with the Union Parishad, UNO office (Subdistrict Chief Executive Officer), police, and even the local Army base to protest the outsiders’ activities. While the Union Parishad and police remained silent, the UNO office and army eventually responded. They visited the community, engaged directly with the outsiders, and made it clear that the community’s concerns could not be ignored. Faced with this pressure, the politically powerful outsiders finally decided to withdraw.

As a consequence, when negotiations finally opened, the terms were steep: the outsiders demanded repayment of their initial investment, and the landowners required financial security for a new lease deed and invest in fish farming. For a poor and vulnerable community (without access to bank loans on behalf of community credit, or other financing) this created an almost impossible barrier.

A Turning Point: RtF Re-grants Empower the Community

The breakthrough came with the money from the RtF program. Unlike conventional aid, RtF provided direct re-grants to the community without lengthy bureaucratic processes or rigid donor conditions. For the first time, funds were placed in the hands of the people to implement their own landscape plan.

The community prioritized reclaiming the 120 bigha (7,500 decimal) canal and negotiated a 10-year lease agreement with landowners. The contract included transparent terms: First 5 years: Tk 5,000(EUR 36.00) per decimal and next 5 years: Tk 6,000 (EUR 42.00 ) per decimal (adjusting for inflation). Importantly, all small local landowners were also included this time, ensuring fairness and preventing future exclusion and challenges arise.

By securing a ten-year agreement, the community protected their investment from future elite capture, and in the process, learned how to survive and move forward together.

Accountability and Local Governance

Hajrakhali landscape management committee is responsible for the majority overseeing the lease contract and fish farming. They established strong accountability mechanisms:

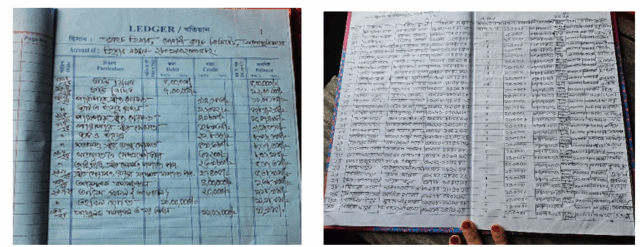

- A notebook and laser book documented every financial expenditure.

- Monthly meetings were held to declare expenditures openly; even illiterate elderly persons could hear,verify accounts and share their opinion.

- Decisions were made collectively, ensuring transparency and community trust.

- An assigned Community volunteer by LMC responsible for continuous monitoring support along with the other community members, and evidence collection through picture taking, live reporting in regular meetings.

This model showcased how regranting support, reflexive mechanisms, can keep power in the community’s hands.

Challenges on the Journey

- Elite capture and exclusion: Outsiders, backed by absentee elite landowners and political influence, attempted to dominate the resources and illegally marginalize small local landowners(who refused to lease land)

- Policy advocacy struggles: Multiple complaints had to be filed at different government offices before action was taken.

- Financial barriers: No formal financial institution trusted the community enough to provide loans without collateral.

The community admitted that, without RtF’s unique re-granting approach, their struggle to reclaim the canal would have remained impossible.

Voices of the Community

“We saw donors or government always giving aid, support and work contracts to community according to their plans or during emergencies. But this is the first time, under RtF, that funds came directly to us for our own plan. It made us confident and empowered.”— Mr. Dablew, community member.

“We fought hard, but had nothing to invest. The RtF grant was a blessing, without it, we would have been hopeless. Now, we can finally shape our dream within our landscape.” —Humayra, A lady community volunteer.

Conclusion

The people of Hajrakhali turned a canal that once symbolized isolation and exploitation into a shared source of dignity, livelihood, and ecological balance. Their journey, from elite capture to empowered community-led fish farming, illustrates how Locally Led Adaptation (LLA), supported by direct community funding, can transform vulnerability into resilience.