by Martin van Beusekom and Cecilia Borgia

December 20, 2013

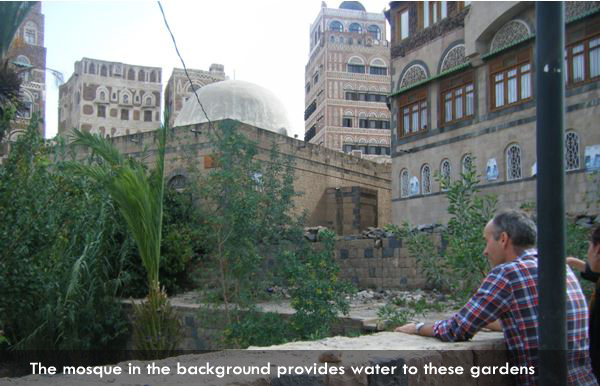

Meandering through the narrow streets of Sana’a Al Kadima in the old city of Sana’a, a UNESCO world heritage, is a true journey through millennia of history. Its labyrinth of mosques, houses and myriad of small shops are a pleasure for the eye, each corner turn unfolding a new mosaic of buildings and colours. When approaching mosques, the urban area tends to open up providing space for green gardens. Edward, our host for this afternoon, explains: “Since historic times, the water used for the five daily prayers leaves the mosque and enters a canal for the irrigation of these gardens”. That right there is a system that reuses greywater for productive and social functions.

These gardens have been a prominent source of food for Sana’a’s dwellers. They played an equally crucial role during the 2008 food crisis. Yet nowadays, parched groundwater wells and complex tenure claims have drifted more than 50% of them into abandonment.

Traditionally – and still now – mosque gardens or almaqashim are waqf property, meaning they belong to the religious community and are ruled by the imam of the mosque. Ancestral arrangements accord poor people special rights to cultivate and irrigate the garden and to sell part of the products, a sort of social security mechanism. These rights are inherited and cannot be transferred, although unofficially there exists a covert market for these lands. Communities living in houses facing the gardens can benefit from a share of the produce, enough for a daily meal. However, they cannot cultivate the plots themselves or harvest and market the produce.

Nowadays, dwindling water resources and a changing institutional context, which is no longer supportive of the original functions of these gardens, are threatening their very survival. As Edward suggests: “Overlapping mandates and claims made by different authorities cause a state of quiescence where nothing is done at all, as involving all institutions would provoke clashes between conflicting interests. To make something happen fast, it is more effective to engage with individual leaders. The revolution also withdrew social and political attention from some of the gardens – making the ‘lost lands’.”

The difference in maintenance and performance of the 5 private gardens in the old city has largely to do with thepresence of water and leadership by local elders and resourceful youth. The 30-odd public gardens also have to deal with institutional complexity. Before the revolution in 1962, local imams could easily re-distribute user right of the plots in the almaqashim, for instance in cases of owners who were travelling or not maintaining the land properly. However, with the setting up of the Ministry of Al-waqf, property rights became firmly attached to individuals, leaving dozens of plots in public gardens unattended.

This afternoon we meet Emad and Abdullah, two young leaders who are trying to regreen old Sana’a by promoting rooftop rainwater harvesting systems (circumventing vested land or water rights) as a sustainable and viable solution to limited water access for both domestic uses and for the gardens in old Sana’a. Supported by Edward and Sabrina– an American couple that has made Yemen their home since 1970– they were winners of the Phillips Liveable Cities Award 2011. Abdullah invites us to the top-floor guestroom of a traditional multi-storey house in old Sana’a. While comfortably sitting on a mafraj, tasting some delicious sweet grapes and throwing occasional glances out of the stained-glass window over the roofs of Sana’a al kadima, Abdullah explains that the house carries the signs of being a 500 year-old family property. It has witnessed the rapidly changing hydrological conditions of the city over the last 50 years. Till the 1960’s groundwater levels were high enough to meet domestic water demands of its citizens. However, introduction of modern pumping technology – heavily subsidized by the international donor community and diesel subsidies, Edward explains – pushed groundwater levels down. Other contributing factors were tremendous population growth and urban expansion, and water and agricultural developments upstream in the catchment. Edward continues: “the increase in motorized traffic in the 1970’s contributed indirectly to the drop in water levels. The city was paved to ease the circulation of vehicles and to prevent pollution by large dust clouds created at the vehicles’ passage through the earthen streets. This happened however to the detriment of runoff water infiltration and the recharge of the aquifers underlying Sana’a”. Sabrina explains that the hydrological function of road systems was not integrated in the modern urban design:

(i) the sandy roads had the function to allow the recharge of shallow groundwater,

(ii) all the roads around a garden had a very slight slope towards the water basins in the garden, where water run-off was collected.

However, the improvement of the road systems neglected this connection, reducing water storage in the gardens and causing downstream flooding. Nowadays water shortage in the old city is very tangible, Abdullah explains. Besides the drying up of wells, also the government often fails to distribute water in a timely manner, pushing women to fetch water from distant locations. For all these reasons, Abdullah was interested to learn more about the potential of rainwater harvesting on the roof of his house. “Because the house is my property I do not need to consult authorities for approval, and it provides water for our domestic needs (washing clothes, drinking water treated through a silver filter, and watering the garden) in times of failing public water supply. This reduces costs and time to obtain water through other ways”. Not only does the rainwater provide for direct uses, but when it is allowed to infiltrate into the soil – at appropriate spots at the base of the house – it also helps recharge the groundwater. This innovative idea spread first to eight neighbours, and last year the example was followed by a further 20 rooftop-owners.The system, as Edward explains, is very simple and cost-effective, provided that regular and preventative maintenance is carried out.

The picture below shows a typical roof – having a minor slope to the left side, where all water is collected through a pipe that leads to the water storage tank at ground level. Individual houses often have roofs with various parts at different heights. The rainwater is then guided from the highest to the lowest parts of the roof through interconnected pipes. The water of the first rains is not used – due to the large amount of debris that settles on the roof during the dry period – and discharged through purge pipes to the garden. The water from subsequent precipitations is collected in Poly-ethylene storage tanks of either 2 or 5 m3. Edward explains: “the rains in Sana’a can be so intensive that a 2 m3 tank can be easily filled within 24 hours. However, the rainy season is relatively short, so it is best for roof owners to have a large water storage tank to overcome the long dry season. The ground space around the houses is generally limited to a 5 m3 tank. However, Abdullah’ss 5 m3 storage tank has reduced the need to look for other water sources by 70%. He can really really see the benefits and so spreads the idea among others in his neighbourhood. At the moment Abdullah, Emad, Edward and Sabrina are planning for the second phase of the pilot, inspiring people of Old Sana’a to re-integrate traditional practices of rainwater harvesting into their lives. Local, youth-led initiatives of this type are an inspiring proof of citizen’s ownership and power to act upon the threat of urban water insecurity by re-establishing local water cycles. These are ideas worth spreading…supporting! And this is just the start…

Emad Al Sakkaf is an incubator of green ideas. His next one: aquaponics on the rooftops of Sana’a! Check this out. https://skydrive.live.com/redir?resid=EB2E0315374565EF!197&authkey=!ACmkzAqbqdPJr2Q

Related Links:

- Liveable Cities website: http://liveablecities.org.uk/

- Phillips Award website: http://thecityfix.com/blog/phillips-livable-cities-award-winner-rainwater-aggregation-in-yemen/

- RAIN Foundation: http://www.rainfoundation.org/