By Shubham Jain, Arpan Mondal, Pratik Ranjan and Frank van Steenbergen

They are there or they are not there: hedges, marking the field boundaries, separating fields but moreover being a huge harbor of biodiversity, an important enabler of better water retention and local climates and a productive asset in their own right.

Recent field visits in Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh States in India revealed that farmers traditionally planted various plants along bunds. However, these plants were not specifically chosen to create a structured hedge system. Instead, they were selected based on practical, everyday needs or with more economic perspectives, such as providing wood, fruits, or fodder, rather than for ecological or environmental benefits like soil conservation, water retention, or biodiversity support. Most farmers were unaware of the broader advantages that a dedicated hedge system could bring. Plant choices were often guided by familiarity and immediate utility rather than a deliberate strategy for creating hedges. This creates a great potential for hedges in both states.

Farmers selected plants along bunds primarily for their economic value and suitability for local conditions. And some of the following plants were observed during visit.

Pigeon pea (Arhar), a popular crop around the bunds, is an annual crop that serves a dual purpose: it provides a source of food that is rich in nutrients and also acts as a nitrogen-fixing plant, which benefits the soil by enriching it naturally, creating a more fertile environment for other crops. Some farmers have chosen Eucalyptus for its commercial value, as it can be harvested and sold for timber. However, it has a high-water uptake, which can negatively impact neighboring crops and the surrounding vegetation. Farmers observed that rice planted near Eucalyptus grows weak due to the water drawn by its roots. Additionally, Eucalyptus trees do not support undergrowth.

Acacia (Babool) is a commonly observed tree on edges as it requires minimum maintenance and resources and it serves as a source of fodder for livestock, especially for small ruminants. Due to the less dense canopy, other crops can thrive under it. Farmers appreciate this tree for its dual role in protecting soil and providing fodder, making it a practical and sustainable choice for hedges. Jatropha is another popular choice among farmers for hedging. It also grows rapidly and requires minimal water throughout the year, making it a low-maintenance option well-suited for hedges. Farmers use these plants as a natural fencing material, as its dense structure effectively delineates boundaries. Jatropha oil and cake also have multiple uses.

Palm and Date palm trees are commonly found along bunds in Jharkhand. These trees were not planted with hedging in mind but rather as natural boundary markers. Farmers value them for their resilience, low maintenance needs, and the additional benefits they provide, such as wood and seasonal fruit. Gliricidia is valued for its multiple uses, including as a source of manure fodder and its straight growth, making it suitable for hedging. While it provides benefits like enriching soil with nitrogen and being easy to maintain, it is not native to the region. This non-native status requires monitoring to prevent any unintentional spread that could impact local ecosystems. Recently, several NGOs have started promoting Gliricidia as a hedge plant along bunds in demo plots.

Although Lantana is often considered invasive, some farmers use it along bunds for its dense foliage, which serves as an effective natural fence. Its hardiness and resilience make it a low-maintenance choice that thrives in various conditions, creating a physical barrier against livestock. However, it is competitive with native vegetation and invasive nature. Farmers should be mindful while planting. Ipomea species in lowland areas to protect fields from cattle due to its dense, robust growth. This plant serves as a natural barrier, creating an effective, low-maintenance hedge that deters livestock. However, farmers should be cautious about invasive nature; without careful management, it can rapidly spread, competing with crops and native vegetation. While beneficial for field protection, regular monitoring and trimming is necessary to prevent both Lantana and Ipomea from overpowering other plants and becoming problematic in agricultural settings.

Farmers in both state did not deliberately plant hedges with structured hedging benefits in mind, the plants chosen along bunds were selected based on practical considerations that addressed immediate needs. Factors like economic value, low maintenance, compatibility with local conditions, and additional household benefits guided the selection criteria. Below are the primary criteria influencing the choice of plants observed in each region:

Income Generation

In both states, farmers prioritized plants that could provide an additional income source, either through direct sale or through products that could be monetized. i.e., Eucalyptus in Madhya Pradesh was chosen for its high commercial timber value. Farmers valued it for its profitability, as Eucalyptus wood is in demand and provides a direct source of income.

Support for Livestock

For farmers who rely on livestock, plants that could provide fodder or were compatible with grazing were often preferred. Trees like Acacia and Giliricida were selected to provide fodder for small ruminants. Its compatibility with other vegetation makes it a valuable source of animal feed in both Madhya Pradesh and Jharkhand. Also, some of the grasses that are grown on bunds are used as cattle feed.

Minimal Water Requirements

Given the dependence on rainfed agriculture, farmers preferred plants that could survive with limited water, reducing the need for upkeep, i.e., Jatropha was selected because it requires minimal water year-round, making it well-suited to bunds that aren’t irrigated regularly. Its low maintenance needs also make it a convenient fencing plant that delineates boundaries without additional care.

Compatibility with Local Soil Conditions

Farmers chose plants that could easily adapt to the local soil types, often preferring species that could thrive in either loose, newly cultivated soil or more compacted, older soils i.e., Pigeon Pea was preferred in newly formed bunds in Madhya Pradesh due to the loose soil structure, which allows roots to grow freely and supports a healthier plant and its nitrogen-fixing properties also make it beneficial for soil enrichment, contributing to improved crop productivity.

Minimized Impact on Neighbouring Crops

Some farmers considered the impact of certain plants on neighboring crops, particularly in terms of water consumption and shading, i.e., Eucalyptus was planted for timber. Still, farmers noted its drawbacks, as its high water uptake could weaken nearby crops like rice and suppress grass growth due to a lack of under-canopy vegetation. Also, crops with dense canopy like makes shade for the crops, which affects the yields.

Natural Fencing and Boundary Marking

Since structured hedge systems are not widely known, bunds often serve as natural property markers and fences. Farmers selected plants that could provide this function effectively, such as Jatropha, for its dense growth, which effectively marks boundaries. Its physical structure serves as a natural fence, deterring stray animals while requiring minimal maintenance. Palm trees in Jharkhand are valued for their resilience and usefulness as boundary markers; they provide clear differentiation for fields and add to the landscape without extensive care.

Farmers are using bunds for hedges but lack awareness of how these can enhance agricultural sustainability and resilience. The absence of structured hedging systems presents a valuable opportunity to introduce practices that integrate ecological benefits with economic gains, fostering environmental health and boosting agricultural productivity.

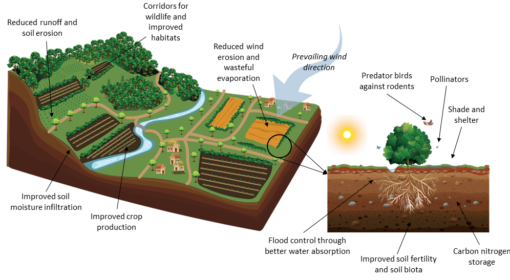

In many parts of the world hedges have disappeared over the last decades, leaving the landscape open and exposed to wind erosion and unprotected against heat. The many functions of this nature-based solutions have been lost in the process, unwittingly. It sometimes appears that they appeared by default and disappeared by default. It is important to make up the balance of positives and negatives – and make hedges again parts of the considerations in improving landscapes. Their many functions as nature-based solutions merit this. This should be supported by careful local planning – appreciating their potential and how to select the mix of species, the locations, where they should be preserved and/or rejuvenated, the area they enclose and connect and the openings and fences. There is a strong case to re-appreciate.

Supported by the RVO project: Agricultural Transition through Productive Biodiversity and Nature Based Solutions