By Molu Tepo, Ibrahim Kabelo, Sahara Ahmed, Hosea Kandagor, Diramu Galgalo, Nancy Kadenyi, Theophilus Kioko, Femke van Woesik

This blog is part of a dossier on locally-led adaptation, featuring insights and lessons from the Reversing the Flow (RtF) program. RtF empowers communities in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan to build climate resilience through direct funding and a community-driven, landscape approach.

This story of Merti in Isiolo County is a clear demonstration of what LLA looks like in practice. When devastating floods hit, the community did not wait for outside help. Instead, they drew on indigenous knowledge, mobilized their own resources, and organized themselves into a taskforce to plan and carry out flood mitigation measures. This locally led action shows how adaptation becomes stronger and more sustainable when communities themselves take the lead, with external partners stepping in only to support and amplify local priorities.

The Ewaso Nyiro River, flowing from the central highlands of Kenya from Mount Kenya, and the Aberdare Ranges, breathes life across 210,000 square kilometre (km²) of arid and semi-arid lands. For the Waso Boran communities of Merti Sub-County in Isiolo, the river is sacred: a nurturing mother, provider of water for people, livestock, smallholder farming, and biodiversity.

But she has become volatile. In recent years, severe land degradation, invasive species like Prosopis juliflora, and climate change have turned the once-gentle river into a raging flood threat. As deforestation and erosion worsen, so does the river’s fury.

From April 2024, the Ewaso Nyiro River overflowed its banks at Godh Rupa and Malka Funan, leaving 763 households displaced in Merti Sub-County, with Merti town particularly hard hit, seeing 570 families rendered homeless. Sericho and parts of Garbatula in Malka Daka-Gafarsa area were also cut off as the river changed its course, and several boreholes and schools were severely affected. The entire village of Iresaboru had to be relocated to a new area, while Badana village remains inaccessible and marooned.

These repeated natural disasters, characterized by submerged bridges, cut-off communities, destroyed homes, and loss of livelihoods, have instilled a profound sense of fear and urgency among the people of Merti.

Rather than wait for external aid, the people of Merti “took the bull by the horns.” They mobilized themselves through an approach that is grounded in local culture and led by community members.

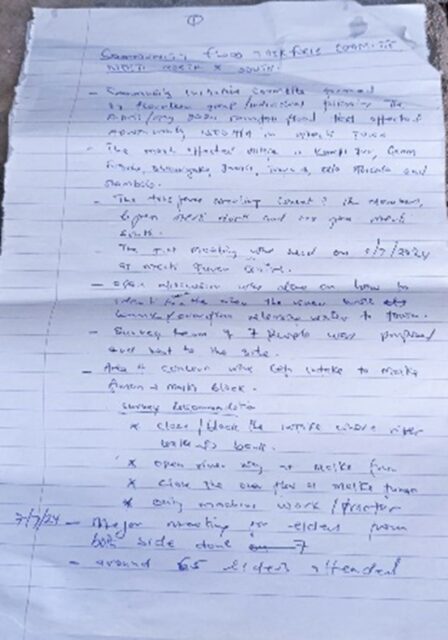

A flood response task force of 12 elders selected from their prior knowledge of the river course to conduct a surveillance exercise along the river, in which they have assessed and identified three urgent interventions: blockage of intake points at Godh Rupa, construction of a diversion channel at Malka Funan area, and rehabilitation of key canal at Malka Funan to safely guide floodwaters.

Mobilizing the community was the next big step where the task force brought together 65 (45 male; 20 female) elders from both Merti North and South to spearhead get buy-in and initiate fundraising efforts. Through this effort, KES 290,000 was raised from households (KES 500–1,000 each), KES 110,000 added by well-wishers totaling to KES 400,000 (about 2,800 Euro) and used for mitigation work.

In April 2025, when the Ewaso Nyiro River flooded again, the community of Merti did not stand by. Guided by their elders, they mobilized resources and worked with their own hands to strengthen the riverbanks and repair canals. It was a massive effort, reflecting their determination to protect their homes and livelihoods.

Each shovel of sand moved and each channel dug marked a milestone. Yet, as Taskforce member Mr. Osman Abdi explained: “The work was done, and it did help to an extent. But because the community still experienced flooding in April 2025, it feels like nothing changed.”

This was not a failure, but a lesson. The Ewaso Nyiro is not a river that can be controlled by force alone. She is complex, shaped by shifting soils, upstream changes, and climate pressures. Real restoration requires more than emergency repairs. It needs a combined approach: using bioengineering techniques such as planting vegetation and creating natural barriers to slow the water, together with carefully designed grey infrastructure like embankments and canals to provide strength where nature alone is not enough.

Despite challenges, including 5KM distances to sites, lack of transportation, and limited funds, the task force persevered. They reached out for support from partners like Northern Rangelands Trust (NRT) for motorbikes, fuel, and vehicles to ease their movement. The experience also revealed important lessons with the need to involve women and youth more actively and the importance of using tractors rather than manual labor in heavy work. As Boru Kampicha reflected while showing the improvements at Malka Funan, “It reminded us of the similar efforts of flood mitigation we made back in 1987.”

To maintain trust and community ownership in managing the Ewaso Nyiro, the Merti Flood Committee organized a feedback baraza. During this meeting, they shared progress updates and explained in detail how every shilling had been spent. This openness strengthened the community’s confidence and reinforced their role as stewards of the river’s restoration. Such transparency is central to the RtF program’s locally led approach, ensuring that decisions and actions remain in the hands of the community, guided by their own knowledge and priorities.

During community feedback sessions, residents stressed the importance of greater participation in future efforts, especially involving women and youth, and called for a more comprehensive, long-term approach that combines physical infrastructure with ecosystem restoration. In response, the Flood Committee was given a full mandate to develop possible plans, reach out to stakeholders for resource mobilization, and broaden representation by including two women, two young men, and two men with disabilities, bringing the total membership to 18.

Based on advice from MID-P and the MetaMeta team during the April 2025 monitoring visit, the committee is now exploring further measures under RtF. These will aim to better direct or redirect floodwaters so they cause less damage. Among the options being considered are clearing invasive prosopis bush and removing debris that clogs the riverbed. In the flat terrain around Merti, such obstructions often force the river to spill out of its main course and flood surrounding areas. The new plans seek to reduce this risk while continuing to strengthen the community’s capacity for long-term river management.

Looking ahead, the taskforce is preparing a fundraising proposal to bring in new allies and partners. Their vision is ambitious: to guide the Ewaso Nyiro back into its rightful streambed and reduce the risks of future floods. This is not only about controlling water but about restoring balance, allowing the river to flow with dignity while securing the livelihoods of the people who depend on her. A stable river means safer homes, reliable water for daily use, and healthier fields for farming.

As community leader Ali Boru explained: “If we succeed, not only will the lower stream communities of Bassa and Sericho drink deep from her bounty, but even our neighbors in Habaswein, Wajir County, will have better access to water.”

The people of Merti show what locally led adaptation and resilience truly mean. When disaster struck, they mobilize their own funds, held themselves accountable through public barazas, and combined indigenous knowledge with practical action. They recognized the need for inclusion, ensuring women, youth, and persons with disabilities take part in shaping solutions. Their efforts prove that real adaptation comes from collective action and a deep relationship with nature. For Merti, working with the Ewaso Nyiro is reconciliation with a river that has shaped their lives for generations.

The story of Merti is a powerful example of locally led adaptation: communities mobilizing knowledge, resources, and leadership to respond to urgent threats. Yet it also raises a pressing question: why are communities left to face such severe challenges on their own? Flood management along a river as large and complex as the Ewaso Nyiro cannot rest on local shoulders alone. While community action is vital, county and national governments remain responsible for allocating budgets and resources for long-term river management, investing in larger infrastructure, addressing upstream drivers such as deforestation and land degradation, and providing the technical and institutional support needed to reinforce community efforts. True locally led adaptation does not mean shifting the burden downward; it means communities define priorities and lead, while governments and partners step up to support, scale, and sustain those efforts. The resilience of Merti should therefore be seen as a wake-up call: if local people can do so much with so little, how much more could be achieved if government and communities worked hand in hand?