by Marijn van der Meer (MetaMeta)

Predicting future climate so that farmers know exactly how to adapt and transform their agricultural practices to maximise livelihoods. This sounds like an ideal scenario, but in reality, this is of course not easy as the climate is unpredictable and changes annually. Where one year, there can be excessive amounts of rain, and the other year can be characterised by large periods of drought. Although precise predictions are not feasible (yet), using a set of climate scenarios can function as an expectation and decision-making tool, both on a large and small scale. This blog shows the use of climate scenarios in the context of communities within the Green Transformation Project (GTP)[1] in Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh in India.

What are climate scenarios?

Scenario development already has a long existence and widespread applications, for example in economic, policy, and environmental models. Scenarios aim to inform policy so that grounded choices can be made. In general, there are two forms of scenario development, the ones that explore futures with different alternative circumstances (including business as usual and extreme scenarios), or the ones that focus on a desired future and the path that needs to be taken to reach this future[2]. According to the IPCC[3]: ‘‘a scenario is a coherent, internally consistent and plausible description of a possible future state of the world. Scenarios are not predictions or forecasts but are alternative images without ascribed likelihoods of how the future might unfold”. In climate research, these scenarios (models) are often large-scale (global/ national) and long-term scenarios, as the global scale fits best with the interactions within the models (large-scale atmospheric and hydrological cycles). However, a key issue is how to fit these global scenarios in local community contexts.

Climate trends and projections in Madhya Pradesh (MP)

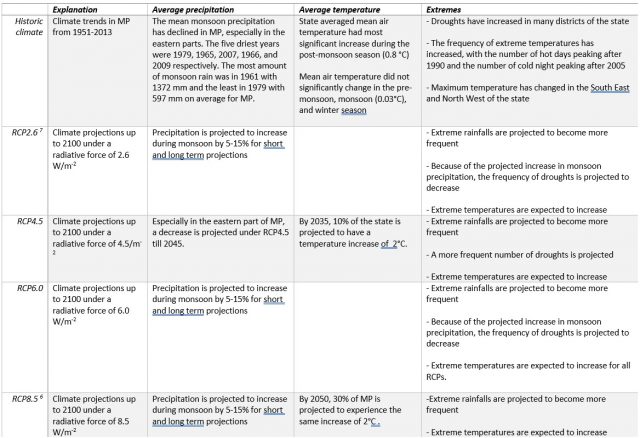

For MP, a large study has been conducted to show spatial climate (mostly temperature and precipitation) trends from 1951-2013[4]. Additionally, climate projections are done under four Representative Concentrations Pathways (RCP 2.6, 4.5, 6.0, 8.5) with five General Circulation Models (GCM) that show the least bias within the monsoon season[5][6].

In this study, Table 1 shows the main conclusion for climate trends (1951-2013) and climate projections (up to 2100). Detailed information about all the spatial maps in MP can be found in the study.

Although some conclusions were drawn, the study also shows the uncertainty of climate projections. Nevertheless, there is a high chance that the threat of climate change will become more severe and irregular. Generally, the research corresponds well with the farmer’s perspective of climate (change). During Focus Group Discussions (Dindori District, MP), farmers’ perspective was mostly a lack of rainfall, delayed start of the Kharif season, more frequent and longer dry spells, and extreme rainfall. Besides, on average higher temperatures are also perceived by the farmers.

Translate large-scale climate projections to local scenario development

Armed with the basic knowledge of state-level climate data, a link should be made to the local scenario development of the communities.

A good example of local scenario development is the co-creation of scenarios with indigenous people in Canada[1]. The main drivers of change were climate change and resource development. Together with the community, four different scenarios were created for 2030 in the form of oral narratives, illustrations, and key discussion points. The researchers often noted that the people saw climate change as beyond their reach. However, there are many ways that people can create improved climates in their field (see blog about Microclimate Management). Through the scenario development process, the researchers recognized social learnings, as people started identifying what is needed to adapt to climate change threats in order to avoid the worst-case scenarios. This resulted in recognizing a few technical adaptation options, but simultaneously some cultural, cognitive, and behavioural barriers. All in all, due to the prioritisation of people’s scenario understanding, some reflection was possible on people’s current needs and capacities to change or transform.

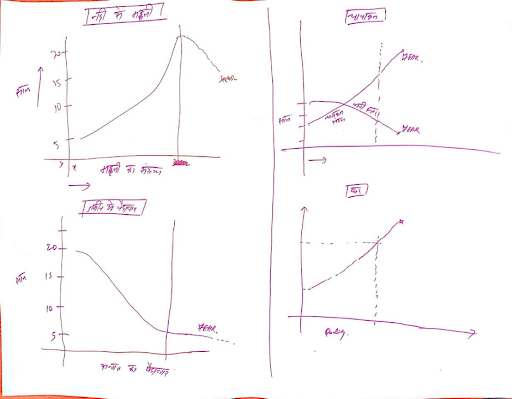

To some extent, the Community-Based-System-Dynamics tool (CBSD), applied by the Foundation of Ecological Security (FES), a partner in the GTP project, connects with the scenario development of resources in villages. With CBSD, the past trends of different resources (forest, water, animals, etc.,) are discussed with farmers and future projections (either fear or hope, so decrease or increase in quality/ quantity) (Figure 1).

Of course, some external factors should not be underestimated when developing the village’s future scenario. Next to climate, policy decisions and market prices determine the (future) outcome partially. In interviews with PRADAN (Indian partner within the GTP project) it is mentioned that if all stakeholders make arrangements that are in the favour of the villages, significant changes can be done in approximately 2 years. However, with the current movement (in which stakeholders are not aligned), fundamental changes should be expected only after 6-8 years. Besides, the functionality of the MGNREGA scheme, a financial scheme under which most NRM interventions are performed, has a big factor in the future outlook of the villages.

Nevertheless, with the use of co-creation of scenarios (e.g., business as usual scenario, flourish village scenario, catastrophic scenario) people’s understanding of the different future paths is triggered. Scenario development can help in expectation building, but also could give a feeling of grip over the current situation. Additionally, it gives a better understanding of the capacity and needs of a community to reach a certain scenario. All in all, co-scenario development helps in stimulating the transformative capacity of a community.

Produced by:

References

[1] Cradock-Henry, N. A., Diprose, G., & Frame, B. (2021). Towards local-parallel scenarios for climate change impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Climate Risk Management, 34, 100372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2021.100372

[1] The Green Transformation Pathways (GTP) project in the Indian states of Madhya Pradesh and Jharkhand aims to create a vibrant circular rural economy based on an extensive exchange of valuable products and services, supported by strong institutions and value chains. This is done through fostering sustainable management of natural resources and regenerative agriculture practices that add to the quality of life.

[2] Bradfield, R., Wright, G., Burt, G., Cairns, G., & Heijden, K. (2005). The origins and evolution of scenario techniques in long range business planning. Futures, 37, 795–812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2005.01.003

[3] IPCC. (2007). Climate Change 2007: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Working Group II contribution to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Fourth Assessment Report. Geneva: International Panel on Climate Change. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008044910-4.00250-9

[4] Mishra, Vimal & Shah, Reepal & Garg, Amit. (2016). Climate Change in Madhya Pradesh: Indicators, Impacts and Adaptation. IIM Ahmedabad Working paper. WP2016-05.

[5] Pielke Jr, R., Burgess, M. G., & Ritchie, J. (2022). Plausible 2005–2050 emissions scenarios project between 2 °C and 3 °C of warming by 2100. Environmental Research Letters, 17(2), 024027. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac4ebf

[6] van Vuuren, D. P., Riahi, K., Moss, R., Edmonds, J., Thomson, A., Nakicenovic, N., Kram, T., Berkhout, F., Swart, R., Janetos, A., Rose, S. K., & Arnell, N. (2012). A proposal for a new scenario framework to support research and assessment in different climate research communities. Global Environmental Change, 22(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.08.002

[7] The RCP scenarios are coupled with a temperature increase worldwide. For RCP 2.6 the increase is around 2˚C worldwide, whereas RCP8.5 reflects an increase of around 4.5˚C worldwide . The increase in temperature pushes other climate conditions, like wind speed, and relative humidity to change as well.

[8] Cradock-Henry, N. A., Diprose, G., & Frame, B. (2021). Towards local-parallel scenarios for climate change impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Climate Risk Management, 34, 100372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2021.100372