David Mornout (MetaMeta), Joe Ray (RVO), Sandra van Soelen (Simavi), Tomi Haryadi (WRI Indonesia)

This blog is part of a dossier on locally-led adaptation, featuring insights and lessons from the Reversing the Flow (RtF) program. RtF empowers communities in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan to build climate resilience through direct funding and a community-driven, landscape approach.

There is a growing recognition that for climate adaptation and sustainable development to be effective, these initiatives must be largely “locally-led.” But what does “locally-led” mean? Where do local ownership and control come into play? What defines “local” and what does it mean to be “led”? How are solutions developed, and what triggers this process? Additionally, is being locally-led sufficient? Can it fully achieve the goal of resilience?

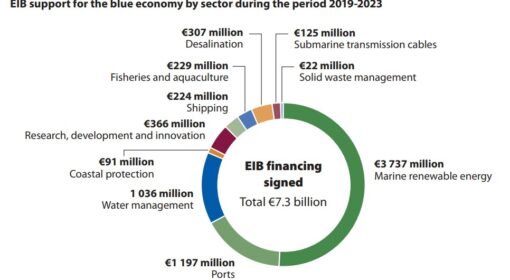

Figure 1 Transparency and accountability – one of the principles for LLA – in practice

In the last week of May 2024, MetaMeta together with the Netherlands Enterprise & Development Agency (RVO) hosted a session on locally-led adaptation (LLA) at the Netherlands Pavilion during the World Water Forum in Bali. The session focused on sharing experiences and best practices within and beyond water- and climate-focused programs. In this short report, the speakers of this session provide an overview of the presentations that took place and the subsequent discussions.

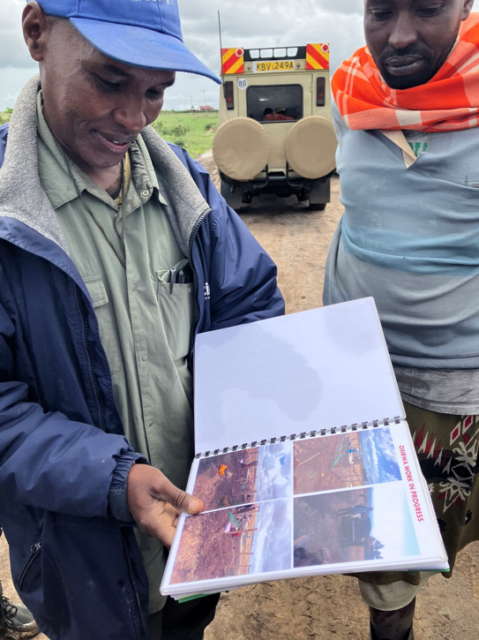

The session opened with an introduction to LLA from Joe Ray, Senior Advisor Climate & Water at the Netherlands Enterprise & Development Agency. The principles (Figure 1) were announced at the 2021 Climate Adaptation Summit in the Netherlands and have since been endorsed by more than 130 organizations, including the Dutch Government.

Figure 2 The Principles for Locally-Led Adaptation

Locally-led adaptation in the Reversing the Flow program

Subsequently, David Mornout (MetaMeta), shared insights and lessons from the Reversing the Flow program. In this program, where MetaMeta serves as the knowledge partner, locally-led adaptation is a key focus. Experiences from the Kenyan NGO IMPACT, one of the 10 hubs in the Reversing the Flow program, gave the participants a clear picture of how LLA can work in practice. David Mornout: “Knowledge development and learning is a crucial integrated part of the Reversing the Flow program. This takes place across communities within a watershed or landscape (in the 5 countries that Reversing the Flow operates in), but also between communities and local governments, and a range of other stakeholders and actors. Lastly, as a knowledge partner, MetaMeta ensures learning between landscapes and hubs at the programme level.”

Experiences in embracing LLA by the Kenyan NGO IMPACT – one of the hubs in the Reversing the Flow program – were shared. David Mornout: “Following internal discussions at the community level, consensus was reached on what they wanted: a water distribution system. They wrote a to-the-point request to IMPACT, and IMPACT regranted the subsidy and left the community fully in charge of the implementation. For accountability towards the other community members and IMPACT, the committee in charge documented the process through photos and bundled them together with the plan and the receipts in one book. The community also set up a scheme for the maintenance of the system.”

Water Justice Fund embracing Locally-Led Adaptation

Later, Sandra van Soelen (Programme Manager at Simavi) and Tomi Haryadi (Director for Food, Land & Water at WRI Indonesia) shared their experiences. Sandra discussed LLA within the Water Justice Fund, while Tomi highlighted the connections between LLA and social forestry in Indonesia.

Sandra van Soelen shared insights from Simavi’s Water Justice Fund, which is providing grassroot grants to the water crisis in Bangladesh, Nepal and Kenya. The Water Justice Fund is a response to the critical intersection of climate change and water, which has had severe consequences for the last mile communities, particularly women, girls and other marginalized groups. These challenges manifest in the form of water related challenges, particularly, flooding, extended droughts, water pollution, heat waves and serve water shortages. Simavi endorsed the eight LLA principles and they are being taken into account in the Water Justice Fund. Sandra shared that decision making over the distribution of the funds is devolved to the lowest appropiate level, as the funds makes funding accessible to women leaders in a local decision making process. The funding mechanism is also patient and predictable, and ensures that the funding reaches women to ensure they can be at the forefront of climate adaptation. The Water Justice Fund invests in local capacities to leave an institutional legacy. And the fund has a flexible design and has a learning component.

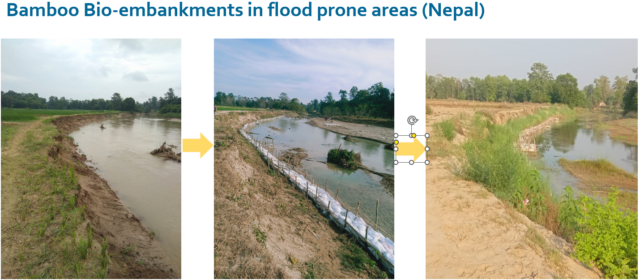

Sandra shared an example of a fund that was given to a women group in Nepal (Mehenatisheel community group). The Mehenatisheel community group has been fighting for the survival of their village after a major flood knocked out the existing embankments alongside the river. Mehenatisheel Women’s Group received a grant of 690 Euro from the Water Justice Fund. Through persistent lobbying and advocacy, the local government agreed to match this fund. The group mobilized the entire community, comprising 57 households, pooling their local knowledge to initiate the construction of bio-embankments. Over a span of 15 days, these dedicated households worked tirelessly to build a 145m-long bio-embankment. Using their indigenous knowledge, they planted vetiver grass along the embankment—a strategic choice given its robust root structure, high drought tolerance, and effectiveness as an erosion control plant in warmer climates.

Locally-Led Adaptation : Beyond water

That the LLA principles are not linked to a specific sector, became very clear in the presentation delivered by Tomi Haryadi, Director for Food, Land, Water Programme at WRI Indonesia. He highlighted how the LLA principles have broad applicability across sectors. Tomi illustrated how these principles were integrated into a social forestry project in various locations in Sumatra, Indonesia. He emphasized the significance of forest conservation for water storage, as trees and forests play a crucial role in the water cycle. Forests impact streamflow regulation, reduce soil erosion, support groundwater recharge, and aid in atmospheric water recycling. By preventing siltation and erosion, forests act as natural filters, retaining a significant portion of sediments and ensuring high-quality water resources that contribute to food security, water sustainability, and livelihoods.

Tomi stressed the alignment between LLA principles and the mainstreaming of social forestry. Social forestry, also known as community forestry, involves engaging local communities in forest resource management and conservation efforts. The government of Indonesia has been actively implementing social forestry programs to address issues such as deforestation, biodiversity conservation, and rural livelihood enhancement.

In terms of climate change adaptation, social forestry plays three key roles: biophysical roles (restoring and maintaining healthy forests, ecosystem services, and acting as a barrier), socio-economic roles (ensuring forests provide essential products, act as safety nets, and generate income), and institutional roles (enhancing local skills, empowering communities to innovate, encouraging knowledge sharing on forest management and climate change adaptation).

Linking LLA to the larger scale

An engaging discussion followed in the second half of the session, where participants exchanged their experiences with LLA in various contexts. Key insights included:

- The importance of reverse accountability. Reverse accountability involves both donors and recipients being accountable for their actions and efforts. In the Reversing the Flow program, this is reflected in communities mapping their progress and expenditures while the program secures multi-year involvement. Abrupt withdrawal of donors or supporting NGOs contradicts the principle of reverse accountability and should be avoided. Transparency in resource flow within LLA programs is also crucial.

- Balancing locally-led initiatives with larger-scale processes. Panelists emphasized that while LLA is essential for shared climate and water prosperity, a sole focus on local processes can overly burden communities with limited capacity. Larger-scale processes, including climate change mitigation, landscape-scale adaptation, and government-to-government efforts, need to complement and align with LLA efforts to share the burdens more equitably.

- The importance of considering diversity. Given the vast diversity in cultures, geographies, and livelihoods globally, there is no one-size-fits-all solution for successfully implementing LLA. The eight guiding principles of LLA reflect methodologies rather than prescriptive activities, acknowledging the need for tailored approaches based on local contexts.

By integrating these insights, the session highlighted the needed considerations for effectively linking LLA to larger-scale processes, ensuring sustainable and inclusive adaptation efforts to head towards – as is the theme of the forum – shared prosperity.