by APIL NGO, supported by Zare Aida

This blog is part of a dossier on locally-led adaptation, featuring insights and lessons from the Reversing the Flow (RtF) program. RtF empowers communities in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan to build climate resilience through direct funding and a community-driven, landscape approach.

To select actions to be funded under the RtF program, the Local NGO APIL in Burkina Faso chose not to start from scratch. Instead, they built on Participatory Community Planning (PCP) processes already in place in each intervention area. These PCPs had been developed with the communities themselves, long before RtF started, and reflect their own priorities.

By organizing local workshops within this existing framework, APIL made sure that decisions stayed grounded in real needs and ambitions. This approach also strengthened local ownership and improved the chances that the interventions would be sustainable in the long run.

How where the PCPs developed?

PCP were carried out within the framework of the World Food Programme (WFP), which is the technical partner and custodian of the method. WFP experts trained APIL and the Technical Services on the approach. The PCPs were developed to improve understanding of livelihoods, sources of household vulnerability, and village land; to identify integrated solutions and develop an action plan for local development:

- Step 1 – Locality selection: Villages were selected based on vulnerability criteria identified by the UN and the Ministry of Agriculture, such as displacement rates, food insecurity, and climate-related hazards (e.g., droughts, floods). In total, 72 villages were selected across the municipalities of Ziniaré, Zitenga, and Korsimoro.

- Step 2 – Community and Leadership engagement: Awareness sessions were held in each village. APIL and government technical services trained Village Development Councils (VDCs), who then facilitated village assemblies to explain the PCP process. Once communities gave their approval, APIL and partners began fieldwork.

- Step 3 – Action Plan Development: Village-based focus groups were formed with participation from technical staff. These groups:

- Mapped local livelihoods and challenges through discussions and community observations

- Conducted vulnerability profiling (by age, gender, displacement status)

- Identified problems and solutions through separate focus groups for men, women, youth, and IDPs

- Validated the final plans in community assemblies

- This process helped ensure that each action plan reflected local realities and community consensus.

The PCP approach can lead to questioning if it’s not a top-down approach. However, it’s important to note that this approach is entirely participatory, with the involvement of communities considered as a source of solutions, not an entity to which a solution is provided. The process allows the community to identify its own needs and define appropriate solutions. The planning tool is based on a co-construction approach that allows communities to express and prioritize their own needs (valuing endogenous knowledge).

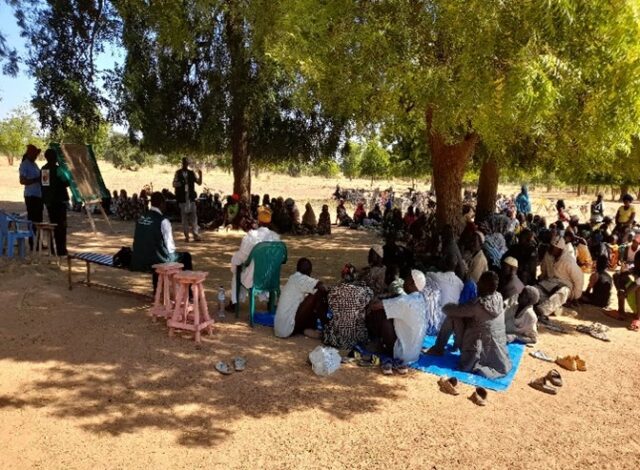

The involvement of communities throughout the process aimed to contribute to greater community empowerment (strengthens social capital by encouraging collaboration, communication and collective decision-making within the community). APIL followed the same dynamic for its local action prioritization workshops, which aimed to arrive at a consensual list of intervention priorities by community. A forum bringing together leaders, women, youth and men, was held in each locality and led by APIL facilitators. The sessions began with a presentation of the RTF philosophy and a summary of the actions mentioned in the PCPs by group (men, women and youth). These actions, written on flipcharts and posted, are read and reminded to the communities. At the end of this, discussions began to produce a list of 10 actions.

What Communities Prioritized

By grouping the proposed actions, the major or recurring themes that emerge are:

- Food Security and Sustainable Agriculture: several actions are directly linked to improving food production and agricultural sustainability. The demand for agricultural inputs and the development of market gardening areas reflects the need to improve agricultural production and resilience in the face of food insecurity,

- Access to Water: access to water for various uses is a priority for communities. The priority given to dams, boulis, BCER and boreholes highlights the crucial challenge of access to water for agriculture, livestock and potentially domestic uses in a context of climate variability for a Sahelian country like Burkina Faso,

- Management of Natural Resources and Environment: some actions enter within the framework of environmental sustainability (creation of runoff water collection basins, land restauration, reforestation, promotion of improved stoves). Land restauration and reforestation actions highlight awareness of land degradation problems and the need to restore natural capital,

- And income-generating activities and training: support for IGAs implementation is mentioned with training. Requests for IGAs demonstrate a desire to diversify sources of income and create local economic opportunities.

Key Learnings

APIL made a deliberate choice to build on pre-existing local planning frameworks to strengthen the effectiveness of its interventions and ensure alignment with community-identified needs. This bottom-up approach helped define priorities for resilience through a process that was already familiar and trusted by communities. Leveraging the existing PCP processes provided several important lessons for effective, locally led development and long-term sustainability:

- Reinforced Local Ownership: By working within established PCPs, APIL avoided introducing external agendas and instead validated tools that communities had already used. This ensured that the priorities reflected local realities and aspirations, reinforcing community ownership.

- Improved Sustainability: Ground-up decision-making within a known and community-owned framework increases the likelihood of long-term maintenance and impact. Interventions are more sustainable when they match local priorities and capacities.

- Efficiency and Trust: Relying on existing tools streamlined the engagement process and built on established relationships. Communities already familiar with the PCP methodology viewed the RtF-supported interventions as a continuation of earlier efforts rather than something entirely new.

- Broad Buy-In Through Multi-Stakeholder Engagement: Involving Village Development Councils (VDCs), decentralized technical services, and community assemblies ensured wide participation and endorsement. This inclusive approach promoted shared responsibility and strengthened the foundation for collaborative implementation.