By NGOs APDA & ORDA, supported by Nardos Masresha and Femke van Woesik

This blog is part of a dossier on locally-led adaptation, featuring insights and lessons from the Reversing the Flow (RtF) program. RtF empowers communities in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan to build climate resilience through direct funding and a community-driven, landscape approach.

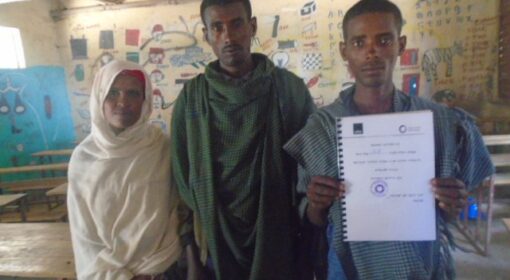

Across RtF landscapes in Ethiopia, community groups supported by local hubs such as APDA in Afar and ORDA in Amhara are using livelihood opportunities as entry points for collective landscape restoration. Small, well-timed incentives help mobilise communities, reduce immediate vulnerability, and enable restoration activities that continue beyond external support.

This approach reflects core principles of locally led adaptation, with decisions taken close to the ground, communities shaping both priorities and design, and external resources acting as triggers rather than substitutes for local action. At the same time, it raises critical questions about motivation, sustainability, and scaling. This blog explores how the model works in practice and identifies what needs to be monitored to understand its long-term resilience.

Incentives as catalysts, not payments

The hubs apply an incentive model that links access to livelihood improvements with active participation in land restoration. Incentives such as revolving funds, farming inputs, animal fattening support, and improved water access provide tangible benefits, but they are not unconditional. Community Based Organisations (CBOs) and watershed user members access them only when they contribute to restoration efforts, with exemptions for differently abled people. Contributions include labour for soil and water conservation works, participation in communal activities, and meeting group responsibilities.

From external triggers to community investment

Within this model, two dynamics stand out. First, external funds trigger initial action. RtF resources are used to start or strengthen income-generating activities that communities themselves identify, prioritise, and manage, including small farms, livestock fattening, improved water access, and other CBO-led enterprises. These benefits reduce immediate vulnerability and create clear incentives to join and remain part of restoration groups.

Second, community contributions multiply the impact. Once incentives are in place, groups do not only receive support; they invest themselves. In APDA sites, members contribute small amounts of money to strengthen ownership, while ORDA sites use revolving fund arrangements. Across both, communities mobilise labour, build group savings, organise rotational work, and expand restoration areas, extending impacts beyond the initial support.

Moving beyond project-based restoration

RtF funding does not pay for restoration activities directly. Instead, it removes key constraints and unlocks local motivation, enabling communities to organise, manage, and expand restoration themselves. Modest incentives act as temporary triggers that set longer-term processes in motion, turning a one-off investment into a continuing cycle of collective action.

This approach contrasts with conventional “project mode” restoration, where funds are used to rehabilitate specific sites and activities often slow or stop once budgets end. The RtF incentive model challenges this pattern by linking ecological work to livelihood improvement, embedding incentives within community structures, promoting village economic and social associations (VESAs), and prioritising group and community ownership over external implementation.

Why motivation and governance matter

This aligns closely with principles of local ownership, resilience building, and long-term adaptive capacity. At the same time, its success is not automatic. Incentive-based models require careful monitoring, as their effectiveness depends on how motivation develops and is sustained over time.

Participation is strongest when incentives respond to immediate needs such as income, water, and food security. By reducing day-to-day vulnerability, communities are more willing and able to invest time and effort in collective restoration. Crucially, restoration is not treated as a separate or unpaid activity. It is embedded within people’s livelihood strategies, making landscape management part of how households secure their futures rather than an additional burden.

Accountability is reinforced through group structures. Bylaws, membership requirements, and peer monitoring create shared responsibility and help maintain engagement more effectively than external enforcement. Over time, as ownership and trust grow within these groups, motivation increasingly becomes intrinsic, reducing reliance on external incentives and strengthening the foundations for sustained collective action.

What needs to be monitored

To assess whether this model fosters long-term resilience, it is important to monitor several key areas: the sustainability of community motivation and whether CBOs can maintain or expand restoration without ongoing external support; equity and access, ensuring women, youth, and marginalized households participate and that incentives do not create exclusion; the quality and durability of restored landscapes, including vegetation recovery and lasting soil and water structures; the economic performance of incentive-linked enterprises and their contribution to collective restoration funds; community contributions and ownership, reflected in ongoing labor mobilization and restoration beyond supported areas; and differences across hubs, which reveal how local adaptations, cultural context, landscape, and governance influence which incentive types are most effective and scalable.