Frank van Steenbergen (GOPA MetaMeta), David Mornout (GOPA MetaMeta), Alamgir Chowdury (Socioconsult), John Marandy (Socioconsult)

Do local water management organizations (WMO) make a difference? And do they not just succeed, but last? How do they last?

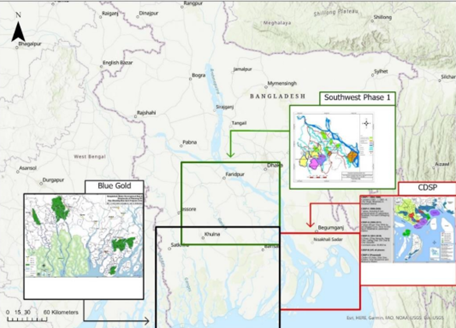

In the past decades, WMOs (water management organizations) have been developed and supported under several development programs in coastal Bangladesh, including the Blue Gold Program, the Southwest Area Integrated Water Resources Planning and Management Project, and the Char Development and Settlement Project (Figure 1). Apart from initiating WMOs, these and other projects have – at the same time – also invested in (water management) infrastructure, as well as in agriculture, fisheries, and marketing – amongst other by promoting new crops, varieties, and techniques.

These three programs had spectacular impacts on increased food security – in terms of higher crop intensity, the yields of main crops and additional crops, the diversity of food production, the quality of diets, income, and access to food

This brings up questions on 1) how do WMOs function, 2) what is their contribution, and 3) how do they last? A recent study on “Food Security and Sustainability of Institutional Interventions in Coastal Zone in Bangladesh”, conducted by GOPA MetaMeta and Socioconsult, answered these questions.

This study was executed against the backdrop of the National Water Policy and the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100. In total, in Bangladesh approximately 3500 WMOs have been established under ten different programs over the years. Yet, despite this large number, many more areas do not have the existence of WMOs. The study in fact found a strong, unmet demand for WMOs in such “control areas.”

This blog presents key findings from the exploration. The full study can be accessed here.

A multi-angle approach to uncover the findings

In the study, the two main research questions were approached from different angles to get more depth and triangulate the findings. Results have been quantified to the extent possible. Four different methods were used:

- Interviews with key stakeholders, in particular from the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB), Local Government Institutions (LGIs), the Department of Agriculture Extension (DAE), and the Local Government Engineering Department (LGED).

- Field survey among 45 WMOs, randomly selected from the data basis and distributed equally over the three programs, including 20% informal organizations in non-project areas.

- Literature and data analysis of WMO monitoring programs as in place in the different coastal programs. These monitoring programs provided valuable insights, although they were in general not standardized and covered only relatively short periods of the entire programs.

- Interviews with project staff of the three programs.

How do WMOs function?

Developing Water Management Organisations (WMOs)

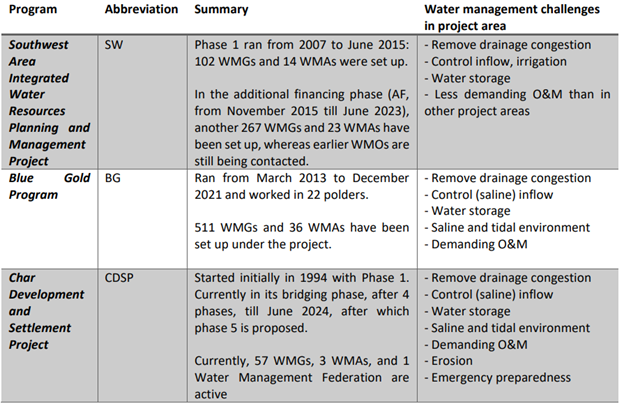

Local water management is an essential but often neglected element in water resource management. Same in coastal Bangladesh. The water management challenges in the areas of the different programs are serious but also vary. Drainage congestion is a major issue in the Southwest area, causing water logging and pushing farm yield and creating healt hazards. In contract, the Blue Gold Program area is located closer to the coast: here river sedimentation and saline inflows are additional critical challenges. In the Char Development and Settlement Project – apart from those other challenges – a main factor is land erosion. To address these varied issues, the different programs promoted the development of formal Water Management Organisations (WMOs) organizing local farmers around water management and operation and maintenance of local water infrastructure. Table 1 is a short overview.

The formation of the WMOs made a difference in the systematic construction of relations between otherwise loosely connected water users, allowing them to take up joint activities. One basic set of tasks is around the operation and maintenance of local water infrastructure. The WMOs were supposed to execute include sluice operation, the cleaning of drains (khals), and embankment maintenance.

The WMOs were also to be in charge of local water resource management – such as the balancing of competing demands between different land and water users within the service area. The classical compromise in coastal polders is between agriculture and fishery – each having different requirements for water levels and water quality, in particular salinity.

These two mandates differ. Maintenance has an intermittent and a rather passive character: it is only needed occasionally, and members of the organization only need to become active when an urgent maintenance problem arises, such as the complete sedimentation of a canal. When a local water management organization solely focuses on maintenance, and is active only occasionally, there is a large chance of it withering away.

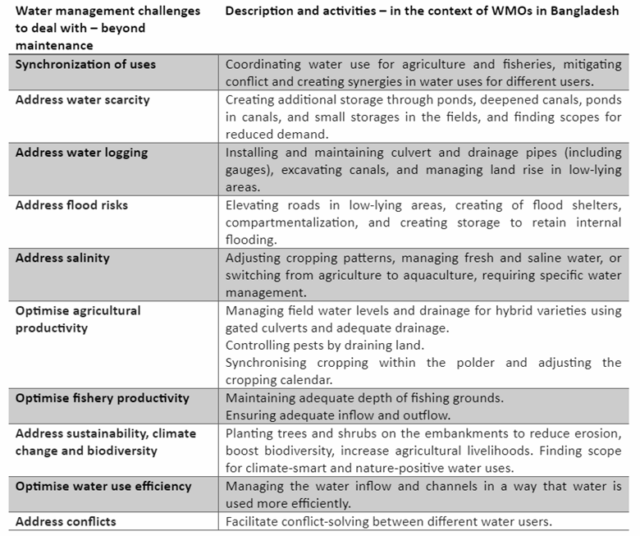

This is different with local water management. This is a constant duty and a key factor in shaping agricultural outputs and livelihoods. It is the often-unfulfilled potential too – as the interest in the establishment of WMOs by water agencies has been more to create the lowest tier in operation and maintenance. The importance of local water management is discussed in more detail in another blog, which also outines the water management challenges that WMOs in Bangladesh have the potential to deal with beyond mainteancne (Table 2).

WMOs in O&M and asset management – grey areas

With regards to local O&M the study found that there are moreover several gray areas where it is not clear in reality who is expected to do what. One concerns the desilting of the drainage canals (khals). Whereas WMOs oversee the removal of obstructions, the cleaning of the khals is often done by Labour Contracting Societies paid from the budget of the BWDB and possibly contracted through the WMOs. There is no cost contribution of the WMOs here. The funding for desiltation by BWDB (or sometimes from local government contributions) thus creates a twilight area.

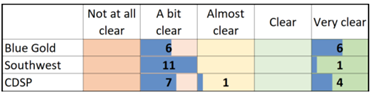

A second area of confusion is the replacement of the sluice gates. The WMOs take care of greasing the hoisting equipment and painting the gates. However, when gates are corroded, a recurrent problem in areas with saline water, replacement is not by the WMOs, but in almost all cases by the BWDB. On a scale of not at all clear, a bit clear, almost clear, clear, and very clear, the WMOs reported as visualised in Table 3. This direct feedback from the frontline confirms that unclear roles and responsibilities are a significant barrier to effective and sustainable water management.

WMOs as (part of) a network

The study found that is useful to see the WMOs not in a narrow sense of organizations that are active or not but more as institutions by which an internal platform between otherwise unconnected individuals is created, and by which linkages with others are organized and by which ultimately prime functions are undertaken (Figure 4). The investment in a WMO is hence not merely the investment in a new organization, but also in new collective networks and linkages and functions that are otherwise not addressed.

The WMO provides for both the collective network of otherwise dispersed water users and the interface with other organizations. The interface is with service providers (such as DAE, Department of Livestock, Department of Fishery, and NGOs) where the WMO connects with the different individual water users within the area, thus, in principle, increasing outreach and reducing transaction costs.

The study found that WMOs also function as collective networks, making it possible to work on the different prime functions (Figure 4), but also, in a situation of high stress, they are a bulwark to safeguard the common interest – as in the history of the Char Development and Settlement Project – where the WMOs were the alternative to the exploitation and powerplays of influential local land grabbers. The WMOs thus empower water users and may also serve as a vehicle to uplift deprivileged groups within the community, such as women, and imbue values of fairness and create a democratic mindset.

Comparing WMOs with the counterfactual

It is also good to compare WMOs with the counterfactual. This was done in the field survey. In areas where there are no WMOs, there are beel committees. These manage the drainage and the water management around it. Those committees depend on individuals and their ability to organize and connect. These informal organizations, however, serve only a narrowly usually problem-defined water management function; outside parties do not recognize them, and for the internal organization depend on the ability and availability of individual leaders. Not to say that WMOs across the board perform well in the legality/internal organization, legitimacy/interface, and functionality, but their scope and potential go quite far beyond the counterfactual informal organizations.

What is the contribution of WMOs?

Impact of WMOs

The three programs had spectacular impacts on increased food security – in terms of higher crop intensity, the yields of main crops and additional crops, the diversity of food production, the quality of diets, income, and access to food. Some highlights:

- Crop intensity increased by 18% (Southwest Area Integrated Water Resources Planning and Management Project) or with 23-91% (Blue Gold Program)

- Yields per ha of main paddy crop increased by 75% (Southwest Area Integrated Water Resources Planning and Management Project)

- Cultivation of high-value crops increased by 16-25% (Blue Gold Program)

- Egg production increased by 3.5 times, milk production by 2.7 times (Char Development and Settlement Project , phase IV)

- Net incomes increased by 31% (Char Development and Settlement Project); net farm income increased by 131% (Southwest Area Integrated Water Resources Planning and Management Project)

- Households with five months or more of food shortage reduced from 46% to 23% (Char Development and Settlement Project , phase IV)

WMOs play a role in fostering improved food security in the coastal programs in various ways, as summarized in Figure 5.

In summary, the study found the importance of WMOs in water management to be manifest in three broad categories of functions:

- By making it possible to balance interests between competing water users, in particular farmers and fishermen, and by introducing local water management; in the special case of the Char Development and Settlement Project, by being a countervailing power for individual land and water grabbing in char development.

- By being a forum where also women and landless/ marginal farmers are represented and programs targeted at women and marginal farmers can be implemented.

- By being a conduit for introducing new agricultural and aquaculture practices in a broad community of farmers (rather than through elite contact farmers, for instance), resulting in higher crop intensity, higher productivity, and larger crop diversity.

Comparing the structure of the WMOs with the counterfactual informal water management organizations, it is safe to say that the WMOs played a critical instrumental role in the spectacular gains in food security under all three programs.

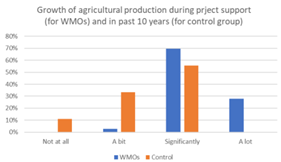

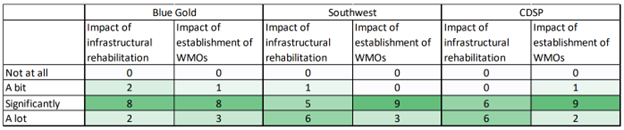

Had there not been formal WMOs, it would have been difficult to reach all farmers, difficult to access women and improve their standing in the farming community, difficult to engage landless and marginal farmers, impossible to have targeted programs. There had been a higher risk of elite capture in the absence of a mechanism to safeguard the interest of all farmers, including those with no political connection, nor had there been a mechanism to introduce better local water management and make the operations of the critical sluice gates on the polder’s boundary accountable to a large group of water and land users and to achieve a balance of interests. This is also supported by data: the growth of agricultural production has overall been (much) larger in areas with WMOs then in areas without WMOs (Figure 6).

WMOs going beyond water

In many cases, the contributions of WMOs go far beyond local water management and basic operation and maintenance of water management infrastructure and. WMOs have helped select locations for water management infrastructure and dug small drains to channel water into khals. Much of the work of WMO has involved working with their communities – solving conflicts over waterlogging and issues that arise during project implementation.

With the WMOs being a conduit for agricultural extension and organizing local activities, it is furthermore observed that Income Generating Activities (IGA) and micro credit are important drivers for the functionality of WMOs. Both these factors were stimulated in the coastal programs.

In Blue Gold, the WMOs used collective funds to pay for income-generating activities (IGAs) in agriculture, poultry, fish culture, small business, and as the capital for local micro-credit. The investments for IGA accounted for 41% to 44% of the total savings. About 60% WMOs use their fund for micro-credit among members. Out of the total 511 WMOs, 309 WMOs of 17 polders are involved in IGAs; the others are not interested in credit functions for investing in IGAs as they find it difficult to maintain account books and other related documents, and they think that loan recovery is a difficult task.

CDRSP also reported that WMOs contributed to the resolution of other social conflicts and discouraged child marriage. WMOs also make an important contribution to disaster preparedness and warning of cyclones. Furthermore, several WMOs work alongside school management committees to maintain these shelters.

It is useful to see the WMOs not in a narrow sense of organizations that are active or not but more as institutions by which an internal platform between otherwise unconnected individuals is created, and by which linkages with others are organized and by which ultimately prime functions are undertaken (Figure 4). The investment in a WMO is hence not merely the investment in a new organization, but also in new collective networks and linkages and functions that are otherwise not addressed.

How do WMOs last?

WMOs post-project

What happened to WMOs when the project under which they been developed and supported finished? The study investigated the continued post-project performance of the WMOs in terms of legality, legitimacy, and functionality in detail. It found that some of the attributes and positive functions were lost, but at the same time a large contribution remained. In summary:

Crumbling legal foundation: After the closure of the program, the legal requirements for WMOs are eroding, unless there is a handholding operation. WMOs are not optimistic about their continued survival.

Functionality persists: In spite of this, the WMOs have been anchored in the local setting – more with elected bodies than with government organizations. Especially the connection with BWDB is not assessed as strong. Over time, there is a risk that the connection with the BWDB further fades away, as there are staff rotations and no systematic platform for interaction. In this respect, the context differs from LGED, which uses a regular monitoring system, awarding best performing local organizations, and where there are regular meetings. Regarding functionality, the WMOs – irrespective of their legality – perform the different functions. In general, functionality does not depend on legality.

In general, a process of institutional erosion seems inevitable, though informally, the new relations and linkages will continue, and the limited scope of functions undertaken – nowadays – by the WMO may still be performed.

Way forward and recommendations

In short: WMOs have played a vital role in the significant improvements in food security achieved through these programs – complementing the rehabilitation of polder infrastructure and agricultural support programs (Figure 7). Their contributions go beyond managing water – they help coordinate cropping patterns, maintain sluice gates, and mediate conflicts over resources. Moreover, WMOs remain – to a large extent – functional even when their legal status or formal recognition weakens.

One cannot solely assess the sustainability of WMOs without including their enabling environment. In this regard, also the recognition (legitimacy) of WMOs by other stakeholders, including governments and BWDB, is very important. The study found that it is important to not just focus on WMOs to ensure participatory water management. WMOs, BWDB, and local government institutes all three need to play a crucial role but that they cannot efficiently function without coordinating their work with other government agencies and stakeholders.

The study recommends to focus on the possible coordination mechanism in the water sector. The above, on the enabling environment and sustainability, also strongly links to “Build, Neglect, and Rebuild” cycle that characterizes the management of the coastal polders. To break this cycle, one needs to address the root causes of this cycle – which is in line with the statement that the sustainability of the polder water system only to a certain (limited) degree depends on the sustainability of the WMOs. Rather the WMOs, as they are now, also contain an unfulfilled potential of a larger contribution to water management within the polders that would add to their functionality and hence continued performance.