Securing the Future of a Culture of Resilience

by Ilse Köhler-Rollefson,

League for Pastoral Peoples and Endogenous Livestock development (LPP)

Nature’s Combine Harvester

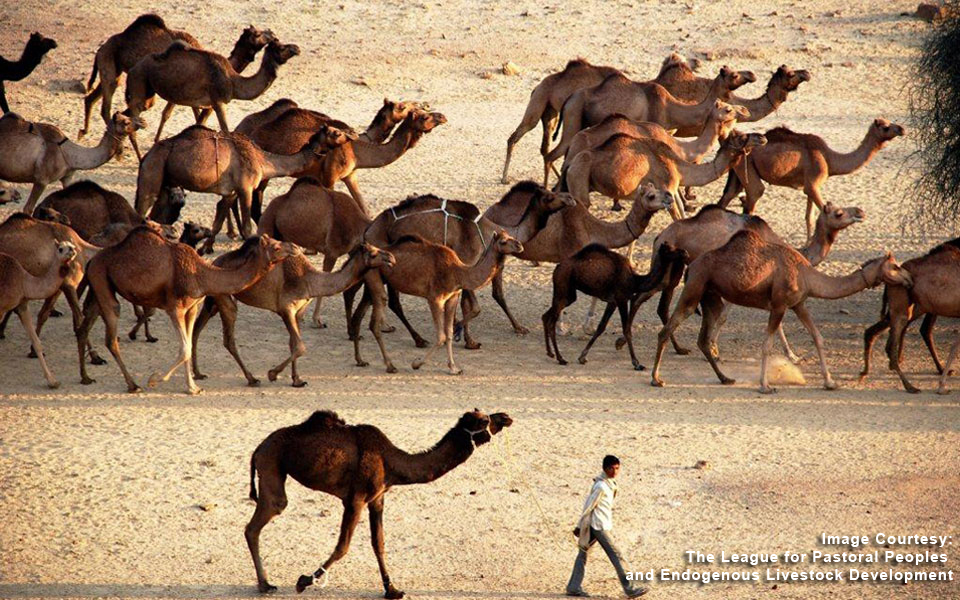

Pastoralism is a highly efficient approach (but also a way of life and a culture) of harvesting the natural and bio-diverse vegetation of arid, semi-arid, mountainous and remote areas by means of herds of domesticated animals – sheep, goats, camel, cattle, yaks, llamas, but sometimes even pigs or ducks. This livestock “harvests” natural vegetation and crop by-products and therefore functions, in principle, like a combine harvester. But it is superior to such machines, as it:

- runs without fossil fuels

- is modular and can be adapted to the size of the area to be harvested.

- can harvest plants on the top of mountains, on steep slopes, on roadsides, in the far reaches of the desert

- immediately processes plants into higher value food, fortified with proteins and valuable amino acids

- is able to reproduce itself, so you never need to buy a new one.

In short, pastoralism is one of the most ingenious and precious human inventions of all time. In order for it to work, it was embedded in cultures and institutions that regulated the interaction between people, animals and land, and were oriented towards achieving long-term sustainability. Examples for such pastoralist cultures are the Raika of India, the Bedouin of Arabia, and the Maasai of Kenya.

Pastoralism, water, and climate change

One of the greatest advantages of pastoralism is that it places no burden on groundwater resources. It requires no irrigation and, during the rainy season, animals can often obtain all their water needs from the plants that they ingest. The livestock kept by pastoralists can withstand a higher degree of dehydration than modern breeds, and have physiological mechanisms to minimize water loss from their systems. Therefore, they can graze far away from water sources. Having endured centuries, or even millennia of combined human and natural selection, pastoral livestock is “climate ready,” so to speak, and can withstand any turn of climatic events and other challenges.

The future of pastoralism

Pastoralism has been around for almost 10,000 years, if archaeologists are to be believed. It is still thriving in some parts of the world, but it is also under tremendous pressure in others: from land-grabbing, population pressure and cultural change. The end of pastoralism has been predicted many times, but so far it has shown itself to be remarkably resilient and often provides a more prosperous livelihood alternative than migrating into urban areas.

Profits can also be substantial as very little money needs to be spent on inputs and as the demand for meat and milk is soaring. In a way, pastoralism personifies the “green livestock economy” and is the antithesis to industrial livestock production which is increasingly criticized due to its negative impacts on the environment, rural livelihoods, public health and animal welfare. Pastoralist and other small-scale production systems are much more sustainable, as well as usually more benign for animals.

Supporting pastoralism

Throughout the world, pastoralists worry about two things: access to grazing grounds and animal health care. If these two issues could be resolved, then there would be sufficient incentives for young people to continue in this occupation. One approach to secure access to customary grazing grounds is the development of ‘Biocultural Community Protocols‘ (BCPs). This is a tool that is backed by the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). It assists communities in developing awareness about their resources and rights under various international legal frameworks. (http://www.community-protocols.org/)

By invoking rights for in situ conservation, BCPs can help to preserve traditional grazing lands and breeds, and uphold sustainable management practices . The process of establishing Biocultural protocols is also an opportunity for raising the awareness of young people about their heritage and the benefits of pastoralism.

Another strategy for interesting new generations in pastoralist livestock keeping is the development of specialty products from indigenous livestock breeds. The meat and milk from pastoralist systems is extremely healthy and nutritious because of the natural feed that the animals consume. LPP is working towards developing a special label called ‘Ark of Livestock Biodiversity,’ that indicates to consumers that a product originates from an indigenous livestock breed and from a production system that helps to conserve biodiversity.

We work with our partners and a range of specialists to create innovative products from local livestock that appeal to niche markets, for instance bio-diverse paper from camel dung, soap from camel milk, and trendy camel wool products. (http://camelcharisma.wordpress.com/)

Livestock Keepers’ Rights

Pastoralists have rights under several legally binding frameworks and international agreements, such as the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP).Unfortunately, they are rarely aware of these rights and there are few efforts to implement them. In order to change this, the concept of Livestock Keepers’ Rights has been developed through an extended series of grassroots sessions with livestock keeping communities. Governments are increasingly supporting this concept. Nevertheless, it will need sustained advocacy to be implemented.

The League for Pastoral Peoples and Endogenous Livestock Development (LPP) was founded in 1992 to provide relief in an acute crisis experienced by Raika camel pastoralists in India. Soon its focus extended to other small-scale livestock keepers around the globe facing difficult challenges and now LPP works globally and locally (through its partners in the LIFE Network) for resilient and socially sustainable livestock production.