By Ishani Sonak

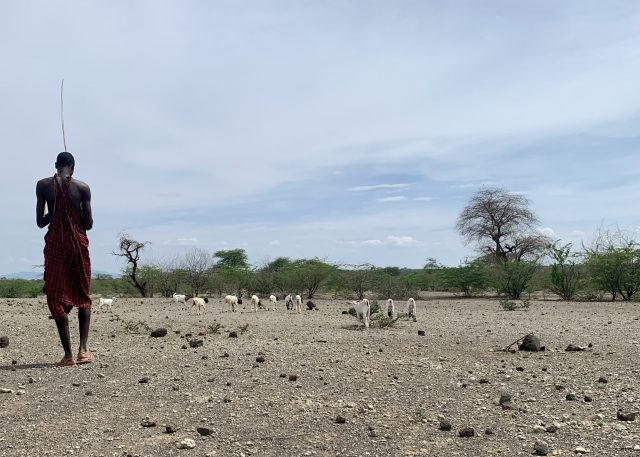

Postcard from Central Rift Valley, Kenya. This is what four years of utter drought look like.

Right at the footsteps of Kilimanjaro, the Maasai community in Kenya is facing a climate induced humanitarian crisis. Five consecutive rainy seasons have failed the community. It is said to be the worst drought in 40 years in East Africa. Uncountable wildlife and livestock are dead as seen above in Picture 1: Dying cow in Shompole village near Kenya Tanzania border, Picture 4: Dead cattle next to the highway in Central Rift, Kenya and Picture 5: Two Zebra dead bodies outside Amboseli National Park, Kenya .

The livestock left behind are so weak that they have got bed soars from laying in the Maasai homesteads due to their boney bodies. A cow that was sold for around 60000 to 50000 KSH i.e. 500 USD is now disposed for 500-1500 KSH or 15USD. The support from the authorities is minimal. The prices of feed have shot up and so have the prices of petrol. Thereby, making it poor economics to buy feed for the livestock and incur a loss by selling the livestock in the market for such low prices.

Besides being the backbone of the economics, livestock is the pivot of Maasai culture and identity. The Maasai elders say that earlier they used to be able to look at a constellation and its position in the sky and predict the rains. Accordingly, they would sell the livestock. However, with the erratics of a changing climate now that knowledge has failed them and left them confused. They are curious about weather predictions so that they can sell their livestock timely, way before it becomes too weak. The Kenyan Meteorological Department claims that there are public meetings, key to information dissemination, but somehow they failed to know about these.

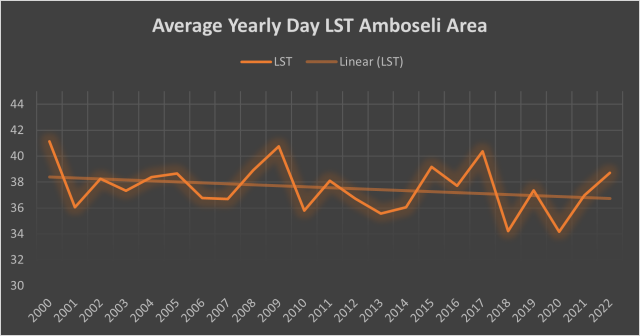

Land Surface Temperature (day LST) data analysis at 1km resolution through MODIS satellite shows that upcoming years may be years of more extremes and unexpectedness in Amboseli region, South Kenya. The trend in annual averages for the past 22 years is a surprising decline (see Picture 2: Average yearly day LST Amboseli (2000-22)). At the same time the highs and lows are getting steeper giving the system relatively lesser time to bounce back raising grave concerns for regeneration of landscape and water availability. Dryer years are hotter but the wetter years are getting cooler than ever before.

The community feels the need to be prepared for the extreme years, for the anomalies. They believe that even if grass cover regenerates, it’s of lesser value to them and their livestock. Their one priority is to capture all water that falls in the area (See Picture 6: Weak cattle moving towards a community water pan in Kajiado County near Amboseli National Park). More importantly, to de-silt the water pans, often done by women around who are in homesteads with weaker, younger livestock. For this to work, however, it has to rain again.