By Uttaran supported by Jannatul Naim

This blog is part of a dossier on locally-led adaptation, featuring insights and lessons from the Reversing the Flow (RtF) program. RtF empowers communities in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan to build climate resilience through direct funding and a community-driven, landscape approach.

In most development projects, baselines are top-down, technical exercises designed by external experts and primarily serve monitoring and donor reporting needs. Under the LANDWATER initiative, part of the RtF program, a different approach emerged that places communities at the center.

Rather than a standard data collection exercise, the baseline became an inclusive process rooted in local ownership and collective learning. It aimed to capture real scenarios, priorities, and lived experiences. Tools such as community listening, stakeholder mapping, open courtyard sessions, and the Community Landscape Insight Framework (CLIF) reflected people’s realities and served as a platform for dialogue. One woman from Soladana shared, “We’re the ones who truly feel the pain, so why isn’t this a top priority? Here, I finally felt free to speak about it.”

Baseline Setup and Philosophy: A Shift in Purpose

The baseline began with key questions: Can a baseline do more than collect stats? Can it support power-sharing and local decision-making? Can communities define success?

The answer was yes. Communities were confident discussing their challenges but sought PRA (Participatory Rural Appraisal) tools to better structure the process, take more ownership, and facilitate their own development planning. In Satkhira, with a literacy rate above the national average, community members felt equipped to document their own plans and expressed a proactive desire to learn. They’ve seen how local organizations use similar participatory methods and are eager to adopt and adapt these tools for themselves. As one member said, “This is our chance to learn something for ourselves. Usually, we just follow the project design and rollout”. Their interest in learning PRA techniques reflects a proactive mindset; an intent to internalize and replicate useful practices without overreliance on the hub.

To respond to community requests and the evolving role of the Landscape Management Committees (LMCs), Hub-Uttaran organized a three-day capacity-strengthening workshop. While workshops often raise questions about being imposed top down. The training was targeted at LMC members who had previously been involved in PRA exercises only as participants. Now, with the baseline declared to be theirs to lead, several frontline community members recognized the need to build their own facilitation skills. This demand came particularly from those already active in community processes and who saw the baseline as a shift in roles and responsibilities.

Of course, not everyone in the community may have felt the same level of ownership. As is often the case, a few proactive individuals tend to dominate such opportunities, which can sometimes lead to unequal influence or even misuse of resources. But the workshop aimed to address this by grounding participants in practical tools for inclusive problem analysis, vulnerability mapping, and shared landscape planning. More importantly, it emphasized that restoration activities must be shaped and carried forward by the community itself, not just managed by a few.

Participants acknowledged that this helped them think more clearly about long-term goals and how to align efforts across groups. At least five individuals said the workshop made a real difference in how they approached the baseline process. The training seems to have met a concrete need: enabling a subset of committed community members to confidently step into a facilitation role and take more responsibility for local planning.

Key Features and Methods

Community-Centered Design: The baseline began with open listening sessions where communities themselves identified their most pressing challenges are chronic waterlogging, salinity, fragile embankments, unsafe drinking water, damaged infrastructure, and threatened livelihoods. These discussions helped surface the real, everyday issues that people feel, see, and struggle with year after year.

Communities chose what mattered to them, instead of only answering a pre-decided checklist of preset questions. Practical concerns like embankment breaches, repeated flooding, or youth migration were seen as just as important as technical data on water flow or soil conditions. It also built trust and showed that their voices and experiences shaped not only what was recorded but how priorities would be addressed. By grounding the process in people lived experiences, the baseline became a tool for dialogue, collective problem-solving, and shared ownership far beyond a one-time survey.

|  |

| Community landscape insight framework planning | |

Participatory Analysis: Community Landscape Insight Framework (CLIF) using courtyard meetings, FGDs, mapping, and transect walks, communities co-developed CLIF to assess:

- Environment: Stressors like salinity and cyclones; solutions to restore ecological balance.

- Livelihoods: Links between water stress and income sources; options for diversification.

- WASH: Safe water and sanitation gaps; infrastructure needs.

- Social Inclusion: Power dynamics; voices of women, Indigenous groups, and others.

- Climate Resilience: Coping strategies; plans to strengthen adaptive capacities.

- Infrastructure: Mapping of physical resources; priorities for repair and protection.

Through CLIF, this participatory analysis ensured that the baseline did not just record facts but sparked ownership, collective reflection, and a shared commitment to reshape the landscape for long-term wellbeing.

Verification and Sharing: After completing the initial assessments, the Landscape Management Committees (LMCs) shared the draft findings with wider community members during an open courtyard session to validate, correct, and strengthen the results. This open verification step-built trust, ensured transparency, and turned the baseline into a collective story shaped by local voices. The refined findings were then shared with key stakeholders including Subdistrict Government officials (UNO), Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) representatives, and other local authorities. These discussions helped spark deeper dialogue on root causes and paved the way for community-led mapping of priority areas and next steps.

Reflections from Uttaran Hub

Based on the Hubs’ experience, the baseline study helped them gain a deep understanding of the local situation by collecting data on water, livelihoods, climate risks, governance, and social conditions. The Hub facilitated communities from the beginning by providing training requested by the community to build their skills in using participatory tools like transect work, FGDs, community mapping, seasonal calendars, landscape participatory analysis etc. Also supported the community by developing baseline narrative report as well as video documentary and community voice record keeping. This made the process more inclusive and helped build trust.

|  |

| Engagement of other stakeholders | |

The Hub used the RtF guidelines and RVO’s suggested topics as a foundation, but tailored them to the local context. This involved simplifying complex questions, translating key concepts into local dialects, and incorporating locally relevant issues. According to the Hub, they felt genuinely motivated by the RtF guidelines, which offered a positive and practical direction for facilitating community engagement in line with the program’s principles. Unlike many donor-driven processes, the RtF modality provided flexibility rather than rigid formats. This adaptability enabled the Hub to lead the baseline process in a way that felt relevant and grounded, both in the community and within their own facilitation style. It also helped structure clear briefings for the communities to understand the purpose and approach of the baseline. Key Hub values were fully embedded in the process, including attention to intersectional vulnerabilities, promotion of gender equity and women’s leadership, advocacy for ecosystem and biodiversity conservation, and protection of the rights of marginalized groups. As a result, the baseline was both methodologically sound and socially inclusive. They are using the baseline beyond just reporting. It plays a key role in facilitating ongoing community dialogues and guiding adaptive planning. For instance, baseline data highlighting flood-time drinking water scarcity directly informed the prioritization of early interventions in affected areas. Additionally, the baseline serves as a reference point for monitoring changes in community resilience over time, that will help Hub to track progress and adjust strategies as needed.

Based on the baseline, communities developed a two-phase plan: first addressing urgent needs (e.g., embankments, bridges), followed by continued facilitation and adaptation. This structure aligns with how communities plan: immediate needs first, vision later. However, the planning process was not without its limitations. Due to time constraints and the urgency of short-term challenges, there was limited space for in-depth, forward-looking thinking about the landscape’s direction over the next 10 years. While some long-term considerations were included, the planning remained largely reactive. This is not necessarily a gap, but rather a risk, one that can be addressed through reflexive monitoring and learning during implementation. After all, for someone living in a waterlogged area, the immediate concern is survival: securing food, a boat, or emergency shelter. Long-term solutions like flood prevention may feel too distant in such conditions. In contrast, donors and hubs are more likely to work with longer time horizons. It’s therefore natural that community plans initially focus on short-term needs. The positive takeaway is that communities did begin articulating some longer-term visions. The ability to think strategically over time is a capacity that often develops gradually. Supporting this evolution through the RtF program could be a valuable learning objective for the implementation phase.

Lessons Learned from Uttaran’s Community-Led Baseline under the RtF Program

- Shift from Extractive to Empowering: Unlike conventional baselines that mainly collect data for donor reports, this approach turned the baseline into a tool used by the community for learning, dialogue, and empowerment putting local people’s priorities and stories at the center.

- Flexible Design, Locally Adapted: Instead of fixed external indicators, the RtF baseline adapted RtF and RVO guidelines to local realities. Complex topics were simplified, local languages were used, and culturally relevant concerns were integrated, making the process truly usable for communities.

- Participatory Methods Built Skills and Trust: Community members didn’t just answer questions they used participatory tools (transect walks, seasonal calendars, community mapping) to analyze and validate their own challenges. This built local skills for future analysis and planning.

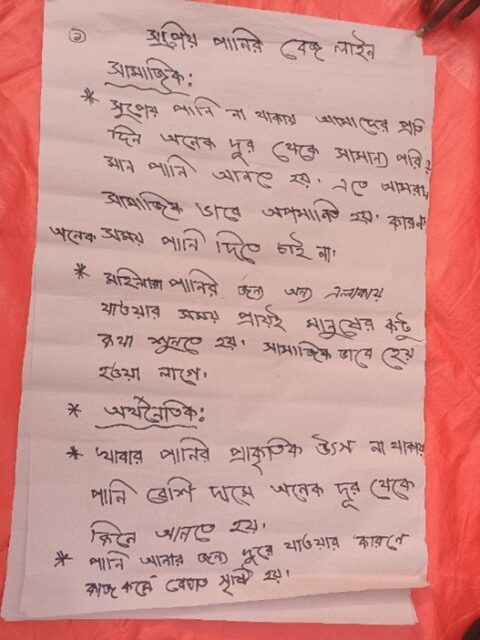

- Community Voice Shaped Content: Through the Community Landscape Insight Framework, communities reflected on their real, day-to-day challenges from embankment erosion and repeated flooding to drinking water scarcity and fragile livelihoods, instead of just producing statistical data. This baseline captured what people truly think, feel, and hope for when it comes to their well-being and future security. It focused on what is in the community’s mind, turning their lived experiences into clear priorities for action. The baseline was documented in a simple written format on brown paper, capturing their exercises using PRA tools and photographs of the activities.

- Living Document, Not One-Time Survey: The baseline is now a reference point for ongoing monitoring, community dialogues, and adaptive planning, not just a static report for donor shelves. During and after implementing the planned activities, the community can compare their current landscape situation with the baseline to measure progress or success and even identify failures and explore better ways to address them. If they face challenges during implementation, they can take quick action and adapt the plan in their own way. In this context, baseline knowledge acts as a starting point. It also helps foster accountability among community members. It serves as an early milestone of a community-led approach where people begin to identify their own issues and gradually figure out how to solve them themselves, learning by doing from both successes and failures.

- Balanced Short-Term Needs with Long-Term Vision (But More Needed): While the baseline shaped practical short-term actions like embankment repair and bridge building, it also highlighted that more structured space is needed for longer-term landscape scenario planning. Because communities needed immediate relief from urgent challenges, some future plans naturally focused on short-term fixes. However, an encouraging sign was that communities still tried to look ahead and think about long-term resilience, even while addressing pressing daily struggles. Going forward, the Hub is committed to closing these gaps by supporting communities to develop clearer, more detailed long-term plans through the upcoming mid-term review and future planning cycles.

Overall, the biggest lesson is that when communities lead baseline design and reflection, they do not remain passive data sources they become active stewards of change, ensuring the baseline itself becomes part of the landscape solution in their eye point of view.