An example from Laikipia, Kenya

By IMPACT NGO, Nancy Kadenyi

This blog is part of a dossier on locally-led adaptation, featuring insights and lessons from the Reversing the Flow (RtF) program. RtF empowers communities in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan to build climate resilience through direct funding and a community-driven, landscape approach.

A water scheme is a structured system designed to provide reliable access to water for domestic use, farming, or livestock. It might be a borehole with a hand pump, a piped irrigation system, or a gravity-fed supply for a village. In many rural and peri-urban areas, such schemes are vital lifelines—for health, food security, and livelihoods.

But access to water alone isn’t enough. The way a water scheme is designed, implemented, and maintained has a direct effect on whether it actually works in the long term. Too often, schemes break down within a few years, or fail to meet local needs because they weren’t built with the community in mind. That’s where implementation approach matters—and why a shift is underway.

This sheet shows an example of a locally led implemented water scheme in Laikipia, Kenya. This example is part of the Reversing the Flow program funded by the Dutch Government where the Kenyan NGO IMPACT regrants 70% of the 1 million funding received directly to local communities. This water scheme was one of the interventions that a community implemented with their received money.

How It’s Been Done: The Conventional Approach

For decades, many water schemes in Kenya have been implemented through a top-down model, often led by governments, NGOs, or development partners. This conventional approach typically looks like this:

- Projects are identified, funded, and designed by external actors.

- Communities are informed or consulted during brief participation forums.

- Contractors are brought in to build the scheme.

- Responsibility for long-term maintenance remains unclear—or stays with the original implementers.

While some projects succeed, many face breakdowns, low community ownership, unclear accountability, and short-lived impact.

What’s Changing: A Locally Led Alternative

Today, more communities, organizations, and funders are turning to locally led approaches—where the people who use and rely on water schemes are the ones who lead and manage them. In this model:

- Communities identify their needs and priorities.

- Communities design the solution and select appropriate technology.

- Financial management, procurement, and repair are handled by the community.

As a result, solutions are tailored to the community’s real needs, values, and environment. This triggers great local ownership and accountability, while having a lasting transformative change. Also, skills are built locally and retained.

|  |

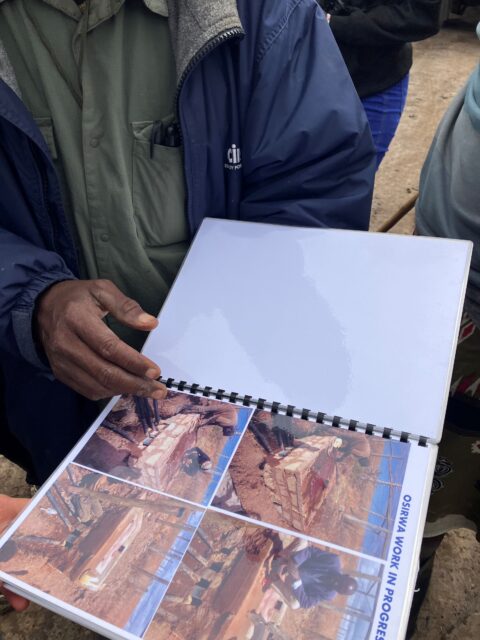

Community led water distribution system in Laikipia

Key differences at a glance

| Externally Led (NGO/Government Approach) | Locally Led (Community Approach) | |||

| Who implements? | Typically designed and constructed by government agencies or NGOs, who bring in external contractors with little or no local involvement throughout the process. | Community members design and build together with the expert/contractor and manage the scheme themselves once operational. | ||

| Budget use | The project budget is usually controlled by the donor or implementing organization. Budget use is often opaque, with little or no transparency or community oversight on how funds are allocated and spent. | The community has ownership of project funds and openly tracks how they are used. The entire group has access to budget information, and spending decisions are made collectively. | ||

| Decision-making | Key decisions—ranging from site selection to technical design—are made by external planners, with community members given limited opportunities to shape outcomes. | Community members make key decisions related to the design, management, and day-to-day operations of the scheme, ensuring that the project reflects their actual needs. | ||

| Technology choice | Technology is often chosen by external actors and brought in as a ready-made solution, with little consideration for local context, capacity, or preferences. | Technology is selected based on community priorities and local needs, with a focus on what is feasible to maintain and use over time. | ||

| Maintenance and repairs | Communities depend on external technicians to conduct repairs, which can lead to long delays due to bureaucratic hurdles. Maintenance is costly and often neglected. | Local technicians and users carry out maintenance, allowing for faster responses to breakdowns. Costs are generally lower, and the system leverages local skills and knowledge. | ||

| Ownership and accountability | Responsibility largely lies with the NGO or government agency. Budgeting, planning, and procurement are often handled internally, with little transparency. Communities rarely see full financial records or plans, limiting their ability to demand accountability. | Full project ownership lies with the community. Financial and planning decisions are made together, with regular meetings to discuss budgets, expenditures, and follow-up on agreements. This promotes transparency and mutual accountability. | ||

| Sustainability | Projects face a high risk of failure after donor funding ends, as communities lack the knowledge, authority, or incentives to maintain the systems. | More sustainable as the community has a vested interest and the skills to keep it running. | ||

| Impact on livelihoods | External contractors do most of the work, offering few employment or training opportunities for local people. Livelihoods are guided by outside actors, with limited room for diversification or locally driven initiatives. | The process empowers communities by creating jobs, enhancing local skills, and boosting the local economy. Households can diversify their benefits and take ownership of related livelihood activities | ||

| Transparency and trust |

Community members often lack access to information about budgeting, procurement, and decisions. This reduces trust and limits their ability to engage meaningfully in the project. | All financial and decision-making processes are open to the community, building trust and promoting a culture of transparency and inclusion. | ||

| Project administration and responsibility sharing | Project administration is handled mainly by donors or contractors, with minimal delegation or sharing of responsibilities with local communities. |

| ||

| Risk management | Risks are managed through generalized plans developed by the implementers, often with limited local input or understanding of local vulnerabilities. |

| ||

| Long term impact | Water schemes rarely bring lasting change to local livelihoods. Job creation is minimal, and the solutions often fail to address the specific needs or preferences of the community. |

| ||

| Community Resilience | Conventional projects make limited contributions to building community resilience, as they often bypass local systems and capacities. | Locally led schemes contribute directly to resilience by empowering individuals, strengthening local capacity, and building hands-on experience that communities can draw upon in the future. |

|  |

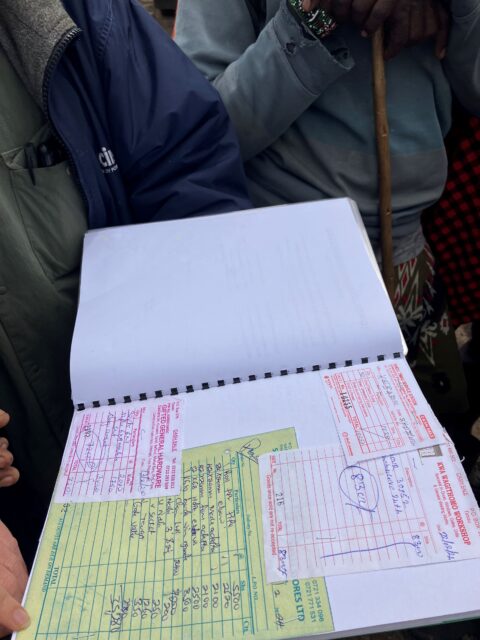

Community accountability and transparency system: photos of the process, receipts, and contracts with local technicians are printed at the local copy shop and bundled in a book to show the other community members