Posted by Rajeshwar Mishra and Frank van Steenbergen

November 8, 2016

(Members of the North Bengal Terai Women’s Federation, a collective of women’s Self-Help Groups in Eastern India)

There is so much energy that can be unleashed by bringing groups together with similar interest and challenges – in learning from each other but even more importantly in creating a self-evolving movement of new institutions.

There is so much strength in horizontal learning – the exchange of knowledge and ideas between likes and peers. In horizontal learning there is no monopoly on knowledge and no hierarchy, unlike in conventional training where there is a teacher and where there are trainees. This is not to say that there is no difference in levels of knowledge and understanding and that horizontal learning happens without planning or structure. Actually this blog argues that there has to be a method in horizontal learning and that there are different things to do in different situations for different purposes.

Horizontal learning shares good practices between people and between groups of people. It entails people coming together and seeing, observing, discussing and learning. A huge advantage is that such experiential learning allows a much finer texture of knowledge – all details of reality and the evidence as given by those that live in it. Class room teaching hardly ever can deliver this.

In sharing experience and good practice in horizontal learning, there are three layers:

- sharing good practices that are already known

- discovering good practices that are worth sharing

- developing new good practice jointly

One can also make a distinction between two processes – a controlled and a free process. In the first process the outcome is known and the efforts is structured. In the second process one provides the stage and the interface but the horizontal learning is of ‘lets a thousand flowers bloom’ nature. Both have merits.

Different methods help to work on these different layers of good practice. If there is no good practice yet, participatory action and learning methods may help to generate these – with much emphasis on group learning and problem solving. This works well in a facilitated way – creating the group that is working together and structuring the discussion. There is always the risk of the capacity to self-organize being taken away by external facilitation and there is a careful balancing act. The other extreme however is for impasses to persist. Another method less targeted way is community coaching – which can be between several communities giving support to one another, evaluating each others strengths and weaknesses on a range of issues

One step up is not to develop good practices, but to discover and capture what is there. The useful practices are often right there but they are not yet known. There are several ways of bringing good practice to the surface. A structured way of detecting good practice is through competitions and best practices awards. Through a network of contacts submissions can be requested that are next assessed and ranked. The best practices are awarded and announced. The excitement and publicity that go with such innovation awards can trigger considerable horizontal learning. A less structured way of uncovering good practices is to organize fairs or ‘melas’. Here many groups are given the chance to present themselves and many are there to witness, discuss, probe and learn. A broad interface will facilitate the learning opportunities but who picks up what is unstructured. This is also the beauty of it.

The last level of horizontal learning assumes that good practices are already known and are carried across by horizontal learning. Exchange visits are commonly used – bringing different groups together to do field learning. The direction of the exchange can be two-way. Either the carrier of good practice is visited, or the carriers of the good practices visit the area where the good practice can be introduced, providing advice and guidance. There are other methods of horizontal learning at this level. Instead of farmer exchanges there can be video documentation of useful practices that are spread within a local network of farmers. This method has been used with considerable uptake by Digital Green. Though the video sharing may looe out on face-to-face contact its big plus is that it generates rich documentation material that remains available. Another powerful horizontal learning tool is the establishment of Farmer Learning Centres, whereby farmers who are the owner and inventor of a good practice provide training to others (against a financial compensation). Setting up such Farmers Learning Centre may be helped with development of teaching material and light business development.

Because horizontal learning and expansion thrives on the interaction between people, it can in principle have all the fun and excitement of people meeting each other. Many of the conveyance systems moreover can make use of the creative and cultural skills that are often abundant and now led to sharing, observing, listening and developing feedback. Songs, music and theatre are particularly powerful. When written or audio-visual products are made, it is good to co-create these as joint outputs. In communication, the dissemination is not the only important part. Joint ownership of a good practice by many parties is a powerful method of upscaling. The steady spread of smartphones provides great opportunities for horizontal learning. Think of WhatsApp groups or community radio that can often be listened to from smartphones and are replacing conventional radio.

But there is much more to horizontal learning and expansion. It can also be a driving force to help develop self-evolving organizations. In community engagement there is the risk of taken the capacity to self-organize out of the communities and make people dependent on the hand holding of community organizers. This leads to organizations that have little chance to survive for more than a short period when they are supported and provided with lots of support and well-meaning attention.

Community groups can go through a process of self-organization by seeing how others are doing it and even visiting them. This would benefit from setting some simple rules of the games– on what constitutes an organization and then developing a systematic network of such organizations. This is for instance how football came to the world – local groups organizing themselves into team and clubs and then joining the larger league. This is also how religious events or cultural manifestations get organised – it thrives on the initiative of people who want to do so and often shine.

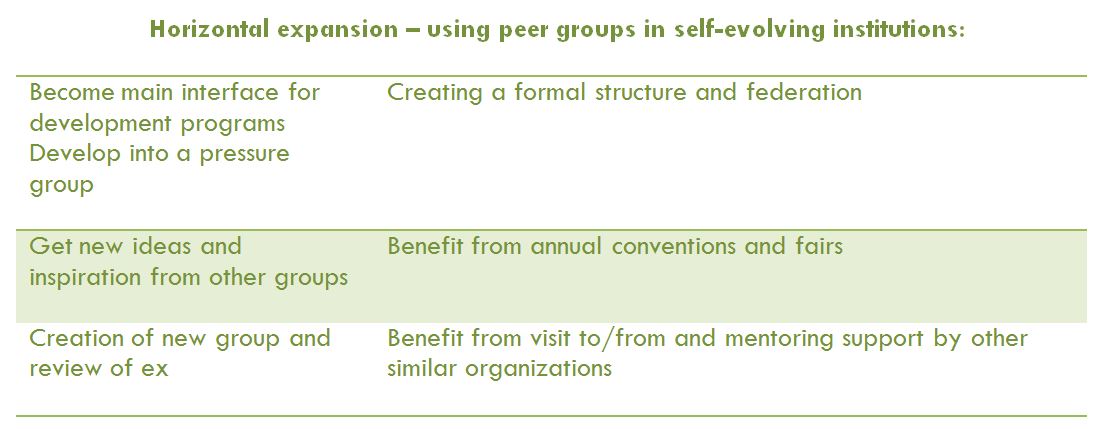

To strengthen self-evolving organization it is important they are in touch with each other and can measure their own achievement against that of peers – providing inspiration and creating beneficial competition. Fairs and melas – in which different groups present their achievements in an atmosphere of joy – are extremely powerful methods to support self-evolving organizations and to bond them in permanent networks and federations.

To close this write up, the experience of the North Bengal Women’s Federation may be given. This federation started small – as many things do – on the strength of thirty women groups with 25 members each, organized and supported by the North Bengal Terai Development Project. The formula was for women group to save money for seven months, after which the collective saving would be doubled by the project and support would be given to start on a joint economic activity. Though this activity was popular and caused the initiation of some interesting joint economic activities, the formula was also judged not to be sustainable, as it depended very much on the incentive of the doubled savings.

A new course of action was taken whereby there would no longer be the bonus. In spite of this there was wide interest for women to create groups – for two important reasons – to be united and big enough in undertaking an economic activity and in some cases to form a joint front in case of domestic abuse. To form group an aspiring group would visit an existing group, take lessons from there and develop their own group. The interest was high and then federations were formed at district level with regular meetings and exchanges between groups, all with funding generated among the groups themselves. In four years 300 groups come into being with an average membership of 25 women. Since then the women federation has continued to thrive. It now consists of three layers: the larger interdistrict federation, the branch federations at district level and then the individual groups. Ten years on, it counts 600 groups with on average 15 members. The woman who was the initial project facilitator is now employed by the Federation and acts as the Secretary. The Women Federation is a main conduit and interface for development programs in the region – be it on functional literacy, rural banking or agricultural development.