Frank van Steenbergen & David Mornout

Water is, of course, at the heart of agriculture. The quantity and quality of water are key factors in shaping agricultural outputs and agricultural livelihoods. Yet it is not only about volume and quality, but also about the timing of water supplies, the water deliveries, the management of different functions, the impact on floods and droughts. Hence, water management, next to quantity and quality, can be considered the third determining component in the water-agriculture nexus.

This is also the case in Bangladesh, a country that is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, particularly to flooding and drought. The country’s geographical location and low-lying deltaic plains make it prone to severe flooding during the monsoon season, while droughts in the dry seasons put agriculture and food systems in the delta further under pressure. Water management – specifically at the local scale – is the key determinant to deal with the water quantity and quality challenges and to ensure agricultural outputs and agricultural livelihoods.

Local water management in Bangladesh

To mitigate the impact of floodings and to protect agricultural lands in Bangladesh, areas of low-lying land, in the coastal area and beyond, are now protected from flooding by embankments and dikes, and have become so-called polders. Water should be drained when fields are waterlogged, while canals should transport water to the fields and ponds when needed. Together, this allows for productive and profitable agriculture.

This logically points out the importance of maintenance; canals should, from time to time, be re-excavated, infrastructure like sluices and gates needs to be maintained and erosion damage needs to be repaired. Re-excavation is specifically in coastal Bangladesh pivotal, given the high sediment load of the water and the frequent tidal flows, frequently providing momentum for the sediments to settle.

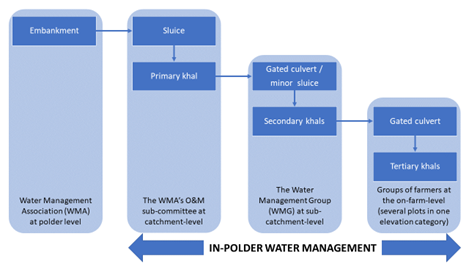

As a response to those maintenance issues and challenges, there have multiple attempts to – successfully – set up local water management organisations (WMOs) in line with the Bangladeshi policy guidelines for participatory water management (2000). These WMOs have been set up in the form of, amongst others, water management associations (WMAs) and water management groups (WMGs). In Bangladesh, WMAs operate at the polder level, while water management groups are operating at the sub-catchment level (Figure 1). Unlike administrative structures, like Unions, Upazilas and Districts, WMOs’ jurisdiction is based on polder boundaries, and thus hydrological units. In line with those boundaries, WMOs report to the Bangladesh Water Development Board – which is part of the Ministry of Water Resources – and not to the local governments.

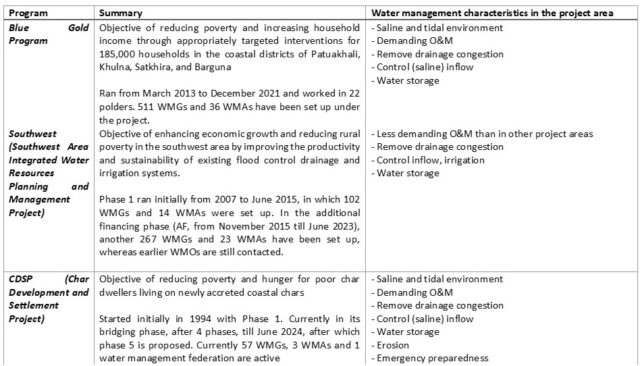

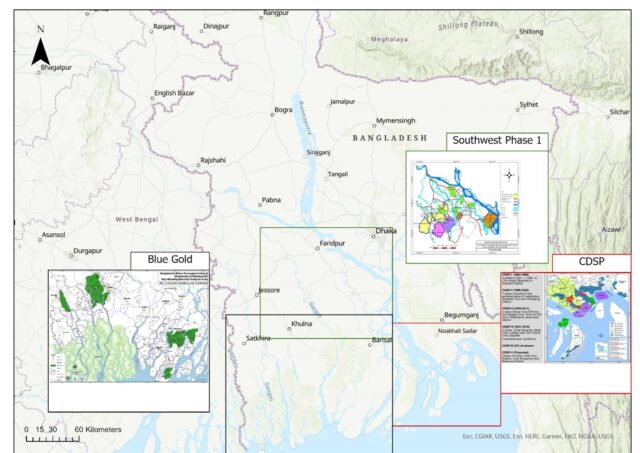

Blue Gold, CDSP and Southwest

Three programs under which WMOs have been set up are the Blue Gold Program (BGP), the Char Development and Settlement Project (CDSP) and Southwest (Southwest Area Integrated Water Resources Planning and Management Project / SWAIWRPMP) (Figure 3). In those programs, the development and set up of water management organizations are key means to objectives in the fields of welfare and economic growth. The table below (Table 1) provides a quick overview of those programs and the water management characteristics of the project area.

Scope of local water management

In those programs, there is a mix of investments in water management infrastructure (hardware) and in local water management organisations (WMOs) (software). The scope of activities from those WMOs is rather big in theory. But, there is a tendency for local water management organisations to focus solely or mainly on urgent maintenance issues. However, maintenance has an intermittent and passive character, meaning that maintenance is only needed occasionally, and members of the organisation only need to become active when an urgent maintenance problem arises, such as the complete sedimentation of a canal. When a local water management organisation solely focuses on maintenance, its sustainability and continuity are under pressure.

However, when truly considering local water management as a key factor in shaping agricultural outputs and livelihoods, water management organisations can tap the full potential of local water management. Hereby, we do not want to neglect the importance of (urgent) maintenance but do want to draw attention to the often-unfulfilled potential of local water management organisations in other aspects of water management.

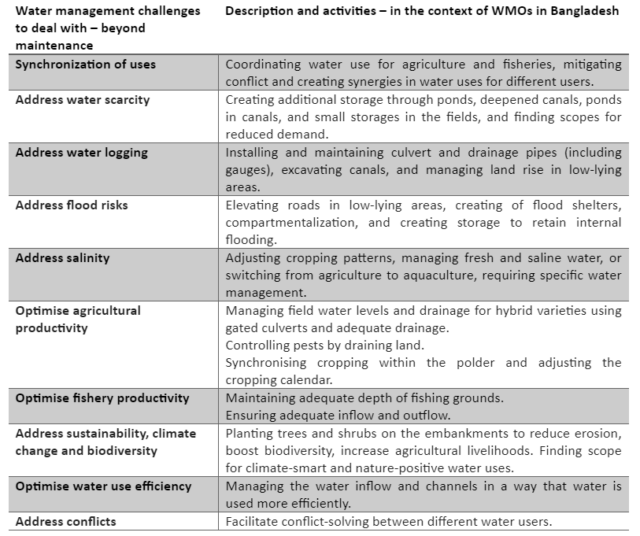

In the context of Bangladesh, WMOs namely have the potential to address many more water management challenges – beyond maintenance, which are shown in Table 2. Addressing those, will not only alleviate the pressure from those challenges, but also contribute to the sustainability and continuity from the organisations themselves.

Table 2 The water management challenges WMOs in Bangladesh have the potential to deal with, beyond maintenance.

An example in which a local WMO successfully manages water for several reasons – beyond maintenance, is provided in Figure 4, in a pilot project from SAFAL for IWRM by Solidaridad (Mornout et al., 2022). In this picture, you see coordinated and synchronized water use in the ponds, managed fishing in the canal, and a temporary bridge for transportation with a pipe for water flow (underwater). The structure to capture fish, in the bottom right, has been largely folded based on the decision of the local water management organization to increase the water-carrying capacity – addressing conflicts and synergizing uses. Next to the canal, mangrove trees have been planted. They improve the water quality via their leaves and strengthen the embankments. Once they are bigger, they can also be used for other livelihoods, as well as manage the local climate and address adaptation and mitigation agendas.

Re-excavated canal in Kalabaria (Debhata, Satkhira, Bangladesh), showing the potential of local water management (David Mornout)

References and further reading

- Asian Development Bank. (2016). Southwest Area Integrated Water Resources – Sharing Knowledge on Community-Driven Development.

- Blue Gold Program. (2021). Blue Gold Program – Lessons learnt from the coastal zone – a call for action.

- Blue Gold Program. (2021). Technical Report 27 Impact of the Blue Gold Program (Endline survey 2020).

- Blue Gold Progam Wiki

- (2023). Char Development and Settlement Project.

- Ministry of Water Resources. (2000). Guidelines for Participatory Water Management.

- Mornout, D., A. Maruf, C. Terwisscha van Scheltinga, 2022. Water management for food systems – case study Bangladesh. Wageningen, Wageningen Environmental Research, Report 3215.

- Solidaridad launches SAFAL for IWRM project in Bangladesh