Ashfaque Soomro and Frank van Steenbergen

There are so many things we can do, but we do not – although they make perfect sense and require little effort.

Houses are not merely a space and building with walls and roofs. They are territories of safety, security, and well-being. The renowned Canadian writer Catherine Pulsifer writes that a home is a place where a person experiences complete protection and peace. That means, the houses should be comfortable by all means. Historically, people have used nature-based solutions to make their homes pleasant and liveable. Using sunlight to light up houses, using wind to cool and using mud to make them fire resistant: a few well-known techniques people always used in many parts of Sindh, Pakistan. The land shaped the way people live and build homes. In these environmental settings, residential housing patterns generationally developed, including mud houses (compacted earth houses), Loh-Kaath (mud wood houses and thatched material), permanent brick homes, and traditional homes with large courtyards. They were the product of generational construction knowledge. Mud walls, thick walls, courtyards, shading, and ventilated verandas have historically been used to reduce heat and make homes comfortable in the scorching summers. Mud plastering on walls and roof were common too.

Moreover, many houses in Sindh (especially in the Larr part) had a mangh or badgir, a wind catcher. The wind catchers provided light and made the house ventilated and cool without electricity. ‘Badgir (بادگیر)’ is a is a Persian word, comprising of two parts; “bad” (باد) means wind and “gir” (گیر) means catcher/receiver.

Wind catchers were widely used in many cities like Thatta, Badin, Sujawal, Shikarpur and some others too. Hyderabad, due to the numerous wind catchers, became famous as Manghan jo Shahar (the city of wind catchers). Badgirs/wind catchers were also common in some parts of Iran, Middle East, Egypt, Afghanistan, North Africa and India. Yazd in Iran is also renowned as the classic “city of wind catchers” with hundreds of these structures dating back centuries. In Bandar-e ʿAbbās (In Iran) and other ports along the Persian Gulf they are normally square towers built on the roofs with vents on one side open to the sea-breezes. There are different designs, in context of regional cultural preferences, but function and purpose of all is same.

Wind catchers are vertical open towers built above the roof, designed to cool buildings naturally, without electricity. The wind catcher has a cover that can be opened and closed by the user to control airflow into the house according to the need or weather conditions. Operation is through a rope, which is pulled to lift the cover and tightened by looping it around a nail or hook fixed on the wall. This system allows residents to adjust ventilation, letting cool air in during hot periods or closing the cover during storms, dust, or heavy rain, while remaining safe and convenient from inside the room. The wind catcher opening face the prevailing wind direction, and when wind blows, it enters the tower through these openings. The breeze entering the wind-catchers would circulate into the room and keep it cool. In summer, the residents would open the shutter before sunset at 5:00 pm and close the shutter around 11:00 am. In the summer the wind comes from the southwest so the mangh face the wind direction. In winter they do the opposite, they opened the shutter around 11 am and closed it around 3pm. This meant they got the daylight from the sun in the south and the warm air that comes from the north. Mangh even used to cool two story buildings and basements as well.

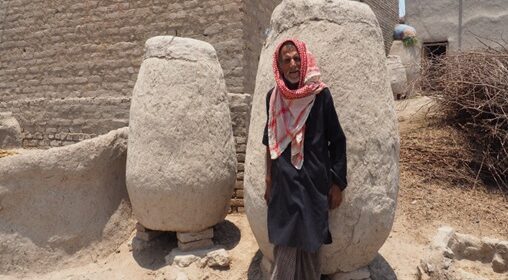

Over the period, this passive ventilation has vanished – even though it was so effective. There are still some houses in rural areas of Sujawal and Thatta that have this natural cooling, ventilating and lightening technology. In current day Hyderabad, the Aga Khan hospital has also applied the technique, which looks very beautiful.

Over the last 60 years the vernacular house designs totally changed to concrete houses, which are thermally uncomfortable. They are high-carbon structures because their construction releases significant amounts of CO₂. They are not equipped with natural cooling, let alone wind catchers, and required substantial amounts energy and carbon to cool with air conditioners. Increasing temperatures turn poorly ventilated, cement and concrete houses into virtual ovens, posing serious health risks to children, women, and the elderly.

Heatwaves and frequent power cuts make the windcatchers even more relevant today. The wind catcher mangh technique offers lessons for modern climate-resilient housing. Architects should revitalize this technique and adapt this concept using modern materials while keeping the same principles, as they are energy efficient, ecstatically pleasing and an important part of the comfort of our built environment.

We probably do only 20% of what there is to do and know only 20% of what there is to know. Even more remarkably, some good knows and do’s move back into the category of unknown and don’ts. Passive natural ventilation, making wind cool our houses, is a good example. We should restore the practice.