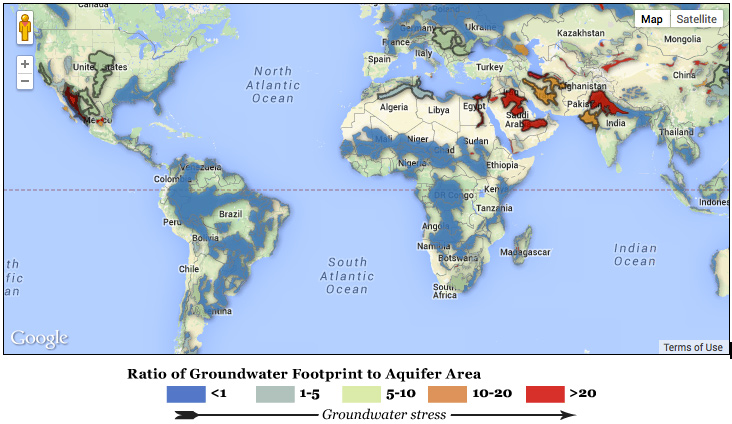

Stress level of aquifers that are important for growing food. Warmer colours are applied to more stressed areas, with large groundwater footprints. (Source: www.waterfoodprint.org, 2014)

A steel pipe bored into the ground attached to a cheap electric pump: this is a pretty comprehensive description of tube wells commonly used by millions of farmers in Punjab, India. For almost three decades, this simple device was the vehicle that helped Punjab drive India’s Green Revolution.

Over the years, Punjab’s tubewells have mushroomed exponentially. The rate has been matched and topped by its groundwater levels, going down half-a-metre every year. Estimates give Punjab another 20 years or so before it runs out of groundwater completely.

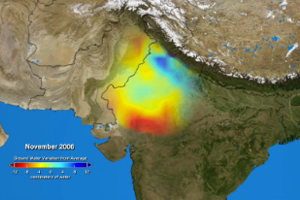

Video: India’s Groundwater Losses and Gains (detected using NASA’s twin GRACE satellites)

Punjab is an extreme case; it does stand out. But by no means is it the only one. Satellite data released in early 2014 revealed that California was on the verge of an unprecedented drought. It was January 17; Governor Jerry Brown declared a drought emergency that same day and appealed to Californians to cut down their water use by 20%.

That freshwater sources are depleting is not news. What we now know is that groundwater lost by aquifers around the world accounts for over 60% of all freshwater loss (between 2003-2010). Over the last decade, we lost 54 km3 of groundwater every year. While increasing population, rising demand and climate change are definitely reasons, this crisis in groundwater is in large part due to decades of bad management and overuse.

Groundwater has been especially susceptible to bad management and overuse due to some of its basic characteristics. It is underground and therefore quite ‘invisible,’ making it difficult to map. There is a dearth of good quality data related on groundwater. Nevertheless, it can be accessed relatively easily by individuals and small groups (for example, all it takes Punjabi farmers is a simple tubewell), which makes it difficult to monitor its usage. All this makes managing groundwater a bit of a challenge as it is. Add to that climate change and the fact that many aquifers run across administrative boundaries, and you get the crisis we are currently faced with.

Managing this underground drought would have to begin with acknowledgement of its severity. In Punjab, for example, this should mean a rollback of low, flat electricity tariffs for farmers that incentivizes over-pumping. Acknowledgement of scarcity should also mean a willingness to tighten our belts, i.e. demand management. The now-concluded APFAMGS project illustrates one way that can be done: providing farmers scientific tools to understand their groundwater systems better, so they can budget their water use prudently.

Once the problem is acknowledged, an array of solutions would emerge reflecting the diversity of social and hydrological contexts. But there needs to be a constant focus on mapping aquifers and collecting data. Apart from managing scarcity, this would also help utilize some of the potentially productive aquifers sitting unutilized.

All natural resources are under stress and many in critical condition. One reason why we should take special notice of the groundwater crisis is that once lost, groundwater sources are much more difficult to replenish than other freshwater sources. “The groundwater is our strategic reserve. It’s our backup, and so where do you go when the backup is gone?” says hydrologist Jay Famiglietti, summing it up in this recent article.

{jcomments on}