Authors: Lucía Moreno Spiegelberg, Karmadine Hima, Ibrahim Danzabarma Abdou-Aziz, Madougou Garba, Luwieke Bosma

Pour la version en français, cliquez ici.

The houses of Gamkalleye cluster in groups, forming parcelled “concessions” that comprehend families and patios. Concessions are a great refuge for the sun and the dust. The families gather in their shared patio, where they cook and clean in the company of their cattle. They are unaware of our invisible run through the bushes and between the legs of the goats. We love to dig in the walls and chew the wicker and the rugs. One day, a storm might come, and the water will flow rampantly through the sewer-less streets, and it will enter our nest and soften the walls of this house. That day, we will run past the parcel across the streets, and we will find a new wall to dig or a new landfill to inhabit. But today, the sun is high, and so will be tomorrow. So we eat the food we find, we steal the rice we can, and we dig, and we multiply, and we keep digging.

The fast urbanization of sub-Saharan Africa has created densely populated areas lacking proper infrastructure and sanitation (1). The cities kept growing, and the population organized itself in slums and large informal settlements to compensate for the low public investments (1). Niamey also grew, spreading through the laterite plateaus and the shifting dunes, swallowing surrounding villages on its way (2). And Gamkalleye, which was so rural and so small, was suddenly immersed in the unpredictable patterns of a city that grew spontaneously.

The growth of Niamey lured black rats, that came from everywhere, and that finally dared to cross the desert carried by the endless flow of trucks arriving at the city (3). These rats came originally from the south of Asia; however, their resilience and voracity following traders and travellers allowed them to find a home in every harbour and on every continent except for Antarctica (4).

Inside the city of Niamey, the black rats soon adapted to the dry climate and the habits of its residents and started to overgrow the populations of the native rodents. Among the native rodents, the common African rat is the most spread in urban areas of Niamey (2). This rodent made the desert its home long ago, also in close relationship with people, and somehow managed to do what many other rodents in many other cities didn’t: they resisted the tidal wave of the black rat population and even overgrew it, if only in Gamkalleye. This phenomenon was observed by the scientists of the SCARIA project who aimed to increase the knowledge of the urban rodent population to find ecological-based ways to manage them at a community level. The reasons behind the rare rodent population composition in Gamkalleye remain unknown; however, the growing numbers of the common African rat, even if native, also constitute a nuance for the residents.

The rodents would dig into the walls of their houses, chew the clothes and furniture, eat bags of rice and maize, and even steal and hide banknotes. Consequently, many of the neighbours tried to control the rodents individually by using chemical rodenticides and traps. However, this only helped to a limited extent, as rodents had plenty of hide-outs in neighbouring houses and landfills and could come back at any point when the threat had faded away. In an urban context, rats have plenty of places to go to in a relatively small perimeter; this emphasizes the need for a community-level approach. One of the aims of SCARIA is to start up conversations with the community about rodents in their vicinity and their perceptions around it, to establish trusted relationships, and to develop insights for community-level rodent management approaches in an urban context.

In Gamkalleye, the inhabitants organized and elected a committee constituted of four trusted women and four trusted men. This committee guided a group of scientists through Gamkalleye, leaving traps in the houses and patios they visited. The scientists collected over a hundred rodents and analyzed them, trying to understand their movements and dynamics. Complementarily, the rodents were sent to a laboratory and are being tested for several human diseases. So far, all tested negative for leptospirosis and hantavirus.

The capacity of rodents to transmit diseases to humans was unknown by Gamkalleye’s population. Probably because the transmission mechanisms are sometimes undirect and complicated, and only some species of rats would transmit certain diseases. Eating rodents can lead to disease; however, sick rats could also pee and defecate among stored food, in kitchens, spreading pathogens even through air (5). Even the people who managed to keep their food out of reach of the rodents might also get sick since some vegetation and some insects can host the diseases of the rats. The plants could be eaten as part of a dish, or the small insects could hide in the folds of the vegetables and be unintentionally consumed (6).

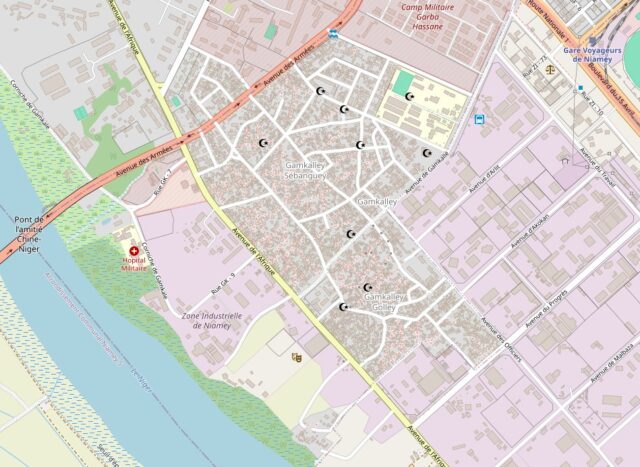

Some diseases can also be transmitted by breathing dust contaminated by rats or drinking contaminated water (7,8). So, the problem with rodents should be tackled from the root. Keeping rodents away from food is necessary, but more is needed; rodent-human interactions should be reduced as much as possible. To do so, it was necessary to know the exact distribution of rodents and those landscape elements that could support their presence. The committee selected five young women and five young men from the neighbourhood who would map the area. First, this group of young people was trained in participatory mapping tools (Open Street Map and ODK). Then, they gathered data from their area for three days.

Complementary to this, the committee organized awareness-raising assemblies in which the scientists and the population of Gamkalleye discussed rodent proliferation, sanitation, hygiene, and how to limit the spreading of rodents. During these discussions, the committee facilitated communication between scientists and the community, leading to a strong mutual understanding that evolved into enthusiasm throughout the sessions.

Working with a committee has shown to be crucial when reaching a population. The members of the committee work closely with the researchers and, since they are also part of the community, they ease the building of trusted relationships and help scientists navigate the area’s intricated social structure, allowing access to its houses and people. The committee would co-organize discussion sessions and mediate between scientists and neighbours to do surveys, find volunteers or get samples of human tissue to analyze potential rodent-borne diseases. The committee would also assist and accompany the scientists during the sampling sessions, helping them decide the best locations for the traps and reaching the scientists when one was full.

The committee will also be helpful in the future steps geared towards developing and fine-tuning urban Ecologically-Based Rodent Management (EBRM) approaches. The residents of Gamkalleye have already expressed their reservations about working with the whole community at once since they worry about communication problems and the potential lack of harmony in big groups. Hence, smaller groups will be created, joining the fight against rodents that will slowly incorporate neighbouring houses, gradually spreading the communal fight.

The last years of the project resulted in understanding the region and its problems, an essential step towards finding a fitting EBRM solution for the area, and another step in developing programs for the intricate and complex management of rodents in urban areas.

REFERENCES

- UN report on SDG11, 2019. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/goal-11/

- Garba M 2012. Rongeurs urbains et invasion biologique au Niger: écologie des communautés et génétique des populations, PhD Thesis, Université Abdou Moumouni de Niamey.

- Berthier, K., Garba, M., Leblois, R., Navascués, M., Tatard, C., Gauthier, P., … & Dobigny, G. (2016). Black rat invasion of inland Sahel: insights from interviews and population genetics in south-western Niger. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 119(4), 748-765.

- Aplin, K. P., Chesser, T., & Have, J. T. (2003). Evolutionary biology of the genus Rattus: profile of an archetypal rodent pest. Aciar monograph series, 96, 487-498.

- ter Meulen, J., Lukashevich, I., Sidibe, K., Inapogui, A., Marx, M., Dorlemann, A., … & Schmitz, H. (1996). Hunting of peridomestic rodents and consumption of their meat as possible risk factors for rodent-to-human transmission of Lassa virus in the Republic of Guinea. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 55, 661-666.

- Himsworth, C. G., Parsons, K. L., Jardine, C., & Patrick, D. M. (2013). Rats, cities, people, and pathogens: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of literature regarding the ecology of rat-associated zoonoses in urban centers. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 13(6), 349-359.

- Stephenson, E. H., Larson, E. W., & Dominik, J. W. (1984). Effect of environmental factors on aerosol‐induced Lassa virus infection. Journal of medical virology, 14(4), 295-303.

- Bharti, A. R., Nally, J. E., Ricaldi, J. N., Matthias, M. A., Diaz, M. M., Lovett, M. A., … & Vinetz, J. M. (2003). Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. The Lancet infectious diseases, 3(12), 757-771.

Pictures