by Shaheber Alga Union, Ulipur, Kurigram, Bangladesh

Friendship NGO, supported by Dr. Jannatul Rushni Naim

This blog is part of a dossier on locally-led adaptation, featuring insights and lessons from the Reversing the Flow (RtF) program. RtF empowers communities in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan to build climate resilience through direct funding and a community-driven, landscape approach.

The chars, temporary river islands formed by the shifting sediments of the Brahmaputra, are home to over a million people in Bangladesh. These landscapes are inherently unstable, shaped by constant erosion and flooding that threaten homes, livelihoods, and infrastructure. In these high-risk zones, conventional top-down climate financing models often fail to reach those who need them most.

In response, Friendship NGO has set up a community-led regranting mechanism for Locally Led Adaptation by the char communities. It directly supports community ownership, inclusive governance, and sustainable landscape restoration by ensuring that financial resources are managed and allocated by the communities themselves, responding to their specific climate vulnerabilities and development priorities. This approach stands in contrast to conventional top-down project financing or microfinance schemes, which often bypass local decision-making. Local communities in vulnerable situations herein are, often in combination with local government, best positioned to develop solutions that are appropriate in context, attuned to local capacities.

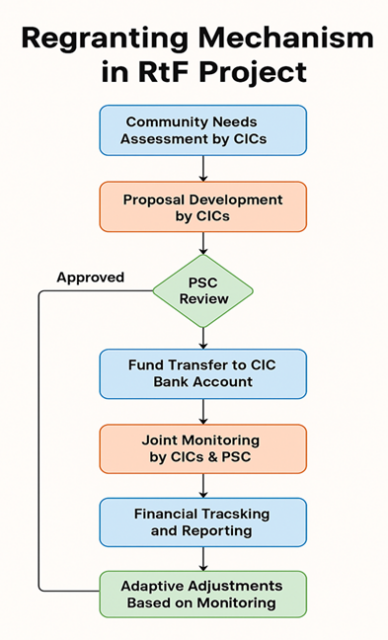

In the bottom-up structure of the regranting mechanism, multiple tiers of community-led platforms play a vital role. At the grassroots level, the broader community expresses its needs and decisions through the formation of Community Implementation Committees (CICs), one for each of the 20 char areas. These CICs are composed of selected and nominated members who represent their respective communities. At the coordination level, a single Project Steering Committee (PSC) is established, comprising representatives from all 20 CICs along with local government representation. The PSC ensures that proposed interventions are contextually relevant, inclusive, and community-driven. Based on participatory assessments, CICs identify local vulnerabilities and develop project proposals, which are then submitted to the PSC for review, feedback, and approval.

Key features of the regranting mechanism

- Decentralized access to climate finance: This decentralized model ensures timely, equitable access to funding for climate adaptation and restoration activities. In remote char areas, where marginal communities especially poor households and women struggle to access loans due to lack of collateral and institutional interest, RtF provides a critical lifeline. By empowering communities to manage resources locally, it offers a pathway forward, rooted in local strength and self-determination.

- Strengthened local governance and transparency: Community-managed bank accounts, selected signatories, and joint monitoring with the Single Project Steering Committee (PSC) ensure transparent fund management and participatory evaluation by different stakeholders in within communities.

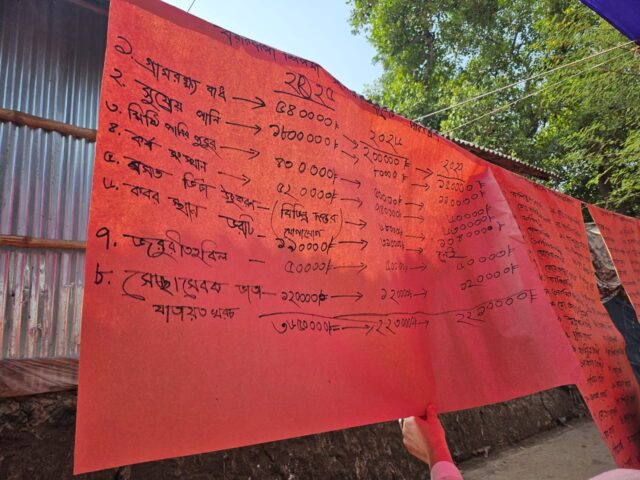

- Adaptive management and learning: The model allows for real-time adjustment. Communities learned from early budgeting errors, refined planning in later cycles, and adapted implementation based on seasonal disruptions. Projects ranged from plinth raising and road elevation to market upgrades, tree planting, and the installation of floating and emergency latrines.

- Bridging community action and policy dialogue: The PSC acts as a bridge between communities and formal governance structures, facilitating dialogue with local authorities, supporting knowledge sharing, and enabling communities to influence public investment decisions.

Operational steps:

- Bank account set up: To promote transparency and community ownership, each CIC selects three signatories- President, Secretary, and Treasurer responsible for managing project funds. The committee prepares the necessary documentation, including a resolution letter, identification, and proof of address, and submits these to the local bank. Bank accounts are then opened in the name of the CIC, addressing institutional identity and financial accountability of the community. To enhance efficiency and oversight, mobile banking tools are also introduced, enabling real-time tracking of fund transfers and expenditures.

- Community-led proposal development: Participatory assessments guide the development of proposals around real climate and development needs, such as water access, mobility, and flood resilience. Proposals are submitted to the PSC for review and feedback.

- Review and approval: The PSC, composed of community and local government representatives, approves proposals based on relevance, feasibility, and alignment with RtF goals. Friendship then disburses funds directly to the CIC bank accounts to begin implementation.

- Implementation and joint monitoring: Projects are executed locally with technical support from Friendship. Monitoring is jointly done by CICs and PSC members through field visits and reflection sessions.

Early results from the RtF Regranting Mechanism

In its first year, RtF supported the implementation of locally prioritized projects including: Cluster village plinth raising for flood resilience, solar lamppost installation, road and market elevation, restoration of native vegetation, floating and community latrines, and homestead and livestock shelter elevation. All activities were managed by the CICs with technical facilitation from Friendship and joint monitoring by the PSC.

Challenges encountered

- VAT & Tax Compliance: Communities need additional support to manage VAT and tax issues, which are new to them, despite overseeing fund withdrawal, procurement, and implementation.

- Over-Budgeting: Initial proposals often exceeded budget limits, indicating a need for clearer guidance on realistic costing and time.

- Frequent Flooding: Disrupts infrastructure and agriculture

- Migration: Disaster-induced relocation affects continuity.

Key Learnings from the Regranting Mechanism under the RtF Program

- Regranting Spurs Collective Action and Community: The regranting mechanism under RtF effectively mobilized by funding through CICs instead of individuals, the approach reinforced collective ownership and made adaptation more inclusive for ultra-poor households. This initiative has inspired some other cooperative or voluntary groups in the area to adopt similar models, submitting proposals to CICs and showing growing confidence in leading LLA efforts for community cattle farming. The mechanism is not only delivering local solutions but also nurturing a culture of community-led planning and ownership.

- Regranting Empowers Livelihood-Led Adaptation for Landscape Restoration: The participatory nature of the regranting mechanism allows communities to frame adaptation in terms of their most immediate needs. While long-term landscape restoration may be difficult for ultra-poor populations to prioritize, livelihood-focused interventions funded through regranting can serve as an entry point. These activities enhance community stability, enabling people to engage more meaningfully in future ecological restoration efforts.

- Regranting Fills a Critical Gap in Financing for Marginalized Char Communities: Unlike other development models where marginalized people depend on individual grants or microloans often inaccessible due to extreme poverty, fragile landscapes, and migratory lifestyles local NGOs and banks struggle to offer financial support without clear guarantees. Now, RTF is extending regranting support through a whole-community approach. By offering flexible funding and empowering communities to make decisions, implement, and monitor initiatives themselves, this model inspires hope and resilience among climate-vulnerable populations.