An example from Laikipia, Kenya

By IMPACT NGO, Nancy Kadenyi

This blog is part of a dossier on locally-led adaptation, featuring insights and lessons from the Reversing the Flow (RtF) program. RtF empowers communities in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan to build climate resilience through direct funding and a community-driven, landscape approach.

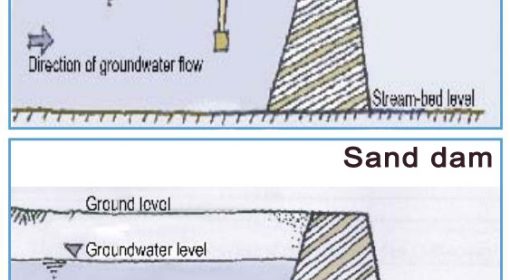

A sand dam is a simple yet highly effective structure: a concrete or masonry wall built across a seasonal riverbed to capture and hold sand. As sand accumulates behind the dam, it traps water that slowly infiltrates and is stored beneath the surface. This hidden reservoir provides a dependable, year-round water source for domestic use, livestock, and small-scale irrigation. In arid and semi-arid regions like Laikipia, Kenya, sand dams are more than just infrastructure—they are essential lifelines. Beyond their practical value, sand dams hold deep cultural and economic significance, particularly in dry grazing areas. They sustain traditional pastoral livelihoods, offering water security in a changing climate and anchoring local resilience in the face of growing environmental stress.

But not all sand dams are created equal. The way they are planned, financed, and built makes a major difference in how well they serve communities over time.

The conventional (Top-Down) model

Traditionally, sand dam projects have been rolled out by government agencies or NGOs. In this model, community involvement typically stops after expressing a general need. The implementing agency then handles the design, budgeting, and construction through a contractor or skilled mason. Local people may be involved as casual laborers, but they have little say in decisions or construction methods. Once the dam is complete, it’s handed over to the community—usually through a newly elected management group. The success of the structure is left to fate, if the elected leadership takes charge, it will be a success, if not it will be mismanaged.

The Locally Led model

The locally led approach is grounded in cohesive, organized community groups—often registered as self-help or common interest groups—that work together to address everyday challenges. These groups proactively engage with NGOs or government agencies to find practical solutions and, in many cases, independently draft proposals to seek funding for their own projects.

In sand dam construction, the community and the funding partner jointly develop a detailed construction plan. The funding entity typically provides support for materials that are not locally available, while the community contributes labor and locally available resources such as sand, ballast, and hardcore. By the time construction begins, a respected and functional management team—elected from within the community—is already in place and involved in every stage of the process.

Once the dam is complete, this same team works with the community to develop a long-term management plan, underpinned by by-laws they have created together. Because the group is already cohesive and accustomed to working collectively, they remain engaged well beyond the construction phase. They take full responsibility for ongoing maintenance and often move on to initiate additional projects—such as vegetable farming, soil conservation, or environmental restoration—strengthening their collective resilience and impact.

This approach is fundamentally community driven. Unlike top-down models, which respond to externally identified needs, the locally led model ensures that the project is aligned with community priorities from the beginning. The community is involved in identifying the need, designing the intervention, and managing implementation. This builds strong internal commitment and cohesion—when people invest in their own solution, they are far less likely to let it fail.

From a funding perspective, the model is also more cost-effective. Donor contributions are lower, as communities supply a significant portion of the inputs themselves. This shared responsibility not only reduces costs but also builds local capacity and ownership.

The strong bonds within these groups also create a foundation for future initiatives. The sand dam often becomes a steppingstone for further community-led efforts that improve incomes, nutrition, and environmental sustainability. In dry grazing areas, sand dams are especially valued—providing critical water sources for livestock and domestic use and supporting traditional livelihoods in increasingly unpredictable climates.

Perhaps most importantly, local leadership ensures that the vision and function of the project continue—long after the donors or government actors have stepped away. This is what makes the locally led approach not just a methodology, but a durable and scalable foundation for long-term impact.

Key differences at a glance

| Externally Led (NGO/Government Approach) | Locally Led (Community Approach) | |

| Who Implements? | Mason or a contractor | A mason together with the community |

| Budget Use | Fully funded and managed by the entity, spent by the contractor | Budget is co-developed by funding entity and community, and managed by the community, with support for skilled labor |

| Decision-Making | Funding entity and contractor | Funding entity and community |

| Technology Choice | Decided by funding entity and contractor | Chosen together by the community and funder to fit local needs |

| Maintenance & Repairs | Left to a selected committee with limited skills and no budget. | Spearheaded by community management team who understands the concept as they were part of construction team. There are clear plans and budget for repairs |

| Ownership & Accountability | No sense of ownership from the community | Community owned and maintained |

| Sustainability | No sustainability plan in place | Clear and agreed sustainability plan is developed |

| Impact on Livelihoods | Minimal, poorly planned and executed | Well planned and executed, huge impact |

| Adaptability to Local Needs | Not factored | Co-designed to meet specific local needs |

| Transparency & Trust | No transparency nor trust | Transparent processes led by the community with clear communication |

| Financial management and reporting | Managed by the entity and contractor, with limited sharing | Joint financial plan with regular updates between funder and community |

| Monitoring and evaluation | No plans or minimal plans only during the project time | M&E is planned and integrated from the start |

| Project administration and responsibility sharing | Contractor is responsible only during the defect liability period (about 6 months) | Community is responsible for long-term success with a shared plan in place |

| Risk management | No risk management plan in place | Elaborate risk management plan developed and executed |