By Satyabrata Acharyya (PRADAN)

This blog is to describe an initiative to promote a new land use for vast chunks of uplands in order to restore degraded lands and create robust livelihoods for small and marginal farmers in Agro-Ecological Zone VII (one of the 15 Agro-Ecological Zones in India) (Figure 1). At the core, the initiative is built around plantations of certain permanent tree species that serve as the hosts for Tasar[1] silkworm. This case captures an attempt of PRADAN, an Indian NGO, working in the most underdeveloped regions in India, to integrate intercropping with plantations through a number of field trials. The objective was to validate a set of assumptions that intercropping practices could trigger vigorous growth in tree plantations in the degraded lands, thereby overcoming the chronic problems of tree stunting due to nutrition and moisture stress. Robust plantations of Tasar host trees could help in enhancing economic returns to the farmers from silkworm rearing, thereby making this land use a viable proposition.

Problem statement

As per the Land Use Data[2] (Reporting Area for Land Utilization Statistics (2014-15)) of India, out of a total of 307 Million Hectare of, about 55 Million Hectare of land comes under uncultivated / culturable waste / fallow categories with various extents of degradation. A vast populace, living on these lands for their sustenance, are frequently impacted by food insecurity, livelihood loss and loss of resilience to withstand the effects of climate uncertainties. The impacts are most pronounced among the Schedule Tribes, women and children.

Coming to the context of Agro-Climatic VII, out of a total area of 26.8 million hectares (representing 8.2% of the total geographic area of India), an estimated 6.70 Million Hectare (25% of the total area) comes under Uncultivated / Culturable waste categories with fallowing being the predominant land use. These lands are mostly unbunded / unterraced with terrain showing gentle slopes (2%-4% gradient) to sharp undulation (>7% slope). The region receives between 1,000 to 1,500 mm of rainfall annually. High rainfall coupled with sharp slopes trigger a rapid erosion of the soil, thereby causing further land degradation. Different studies indicate almost 70% water run-off from the landscape resulting in poor hydrology in the region. Moreover, regular deposits of coarser soil particles from uplands to the low-lying farm lands causes considerable harm to farming.

Uplands are mostly owned by small and marginal farmers. PRADAN’s internal studies (mainly the village studies done by Development Apprentices) show that uplands constitute a third of the total landholding in smallholder households. People are paying taxes for the uplands without any perceptible returns. The changing climatic pattern, manifested by fewer rainy days with intense precipitation exacerbates the process of land erosion and poses a threat to farming in low lands. This way, uplands not only give no gain, they pose even threats for low land productivity. The land-owners lack wherewithal to conserve the uplands and come up with alternative land use (than following) that is sustainable and rewarding.

Interventions by PRADAN

PRADAN’s Tasar sericulture project[3] envisaged promotion of Tasar sericulture-based livelihoods outside the forest areas. The idea was to support local people to raise Tasar host tree plantations in large stretches of degraded uplands, owned by them. In 3-4 years, the plantations were to become ready to host Tasar silkworms every year for the next 50 years. Cocoons are harvested and sold by the silkworm rearers to earn livelihoods.

Plantation raising for sericulture promotion:

The idea of raising plantations of Terminalia spp. in waste / fallow lands was received from the Central Silk Board that demonstrated the model in their research stations situated in the same geography. However, taking the model to the farmers’ field required a number of changes in the technical model, including plant spacing, schedule of intercultural operations, maintaining tree height and shape etc.

So far, PRADAN has promoted 6,460 hectares of Tasar host tree plantations in the wastelands owned by smallholder farmers and other marginalized sections (Figure 2). Tasar host trees are hardy plants and can grow under rainfed conditions in depleted lands. Tasar silkworm rearing in plantations is an attractive livelihood proposition for marginalized households as (a) it utilizes idle assets—wastelands / fallow lands, (b) requires low operating investment (c) involves family labour and (d) offers high returns from silk cocoon sale.

Over the years, PRADAN has evolved a comprehensive method of promoting large scale Tasar host plantations in privately owned waste / fallow lands of smallholder farmers. The method seeks to involve local communities at all stages of planning, implementation and long-term plant protection and maintenance. On an average, each smallholder household would deploy between 0.30 and 0.50-hectare land area for raising plantations. The plantation farmers take keen interest in sustaining the plants as it is a source of major livelihood earning. On an average, each hectare of plantation could potentially offer a net annual earning to the tune of USD 1,200. With a measure of success, the entire model of plantation raising and silkworm rearing, has been demonstrated in the project locations spread over Jharkhand, West Bengal and Bihar. This resulted in significant demand creation in the villages.

In a number of States, such as Jharkhand, Bihar, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal, the department of Sericulture and the office of the MGNREGA Commissioner took up Tasar host tree plantations in private lands to expand the scope of Tasar sericulture and create livelihoods for rural communities. PRADAN was often asked to offer expert support in scheme design, training of government functionaries and in the monitoring of the programme.

Resource Mobilization

So far, PRADAN mobilized investments for plantation raising mainly from the private donors, philanthropic foundations and later on, from the Government programmes such as Swarna Jayanti Gram Swarajgar Yojna (SGSY) and Mahila Kisan Swashaktikaran Yojana (MKSP), both under the Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India and Special Central Assistance to Tribal Sub-Plan Areas (SCA to TSP) as also from NABARD.

Shortcomings in the model

PRADAN started promoting silkworm rearing in plantations from the year 2000 onwards. The initial years were spared for building good learning experiences in the community along with setting up systems for egg supply, aggregation and marketing of Tasar silk cocoons. Over the years, it has been realized that the productivity / carrying capacities of the Plantations are about 60 percent of the original design. Though the income generation out of Tasar rearing continues to attract smallholder farmers, yet there exists considerable scope to enhance income. Also, it is important to match the income with the growing needs and aspirations of the farmers. The plants, mostly grown in the fallow / degraded lands show an overall reduced growth with lack of uniformity observed across the plant stock.

Consultation with experts from the Central Silk Board and ICAR along with plantation farmers suggested that the growth of plants gets affected most significantly when the trees face problems of stunting in the initial 3 years. At later stages, the plants would never recover fully. It was evident that stunting was caused owing to nutrient and moisture stress in depleted soils and young plants are most vulnerable to such stresses.

For several years, PRADAN tried out a number of measures to safeguard young plants from moisture and nutrition stress. Increase in pit size / volumes, application of higher quantities of manures, watering plants in the summer season were the salient measures. Though proven effective, these measures required at least 35% higher investments that became difficult to mobilize from the mainstream.

Promoting intercropping in the plantations

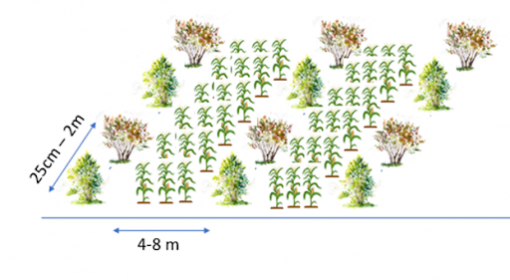

In the summer of 2022, PRADAN planned to introduce the practice of intercropping with legumes / pulses in the plantations (Figure 3). The hypotheses behind the interventions included the following:

- Light tillage in between the plant rows will break the hard soil crust to allow water to enter deeper soil layers,

- Intercropping will result to ground coverage by crops to regulate micro-climate, specially prolonging moisture retention and check soil erosion,

- Intercropping with pulses will help in nitrogen fixation and faster growth of intercrops will cover the ground quickly to control growth of weeds and reduce tree-weed competition,

- Nitrogen fixation, moisture retention and addition of bulk volume of biomass through pulse crop residues will enrich the soil to support Arjuna plants to attain growth and vigour,

- Tasar silkworm rearing in plantations starts after 3-4 years of planting. Meanwhile, the farmers would be benefited in the immediate term by ways of pulse harvest and income. This is important to strengthen their attachment to the plantation activity.

- Intercropping activity would be less costly and could be included in the unit cost of the plantation scheme.

A total of 120 hectares of plantation area was selected in Godda district of Jharkhand to undertake intercropping trials. The total area was constituted of 7 plantation plots, with sizes in the range of 10 hectares and 26 hectares. Lands were undulating. Soil was coarse gravelly to sandy types. The soil was apparently quite depleted.

- There were 3 (three) treatment measures applied; Intercropping with (i) Sesbania bispinosa (local name Dhaincha) (Figure 4), (ii) Vigna radiata (Common name Black Gram), (iii) Vigna mungo (Common name Green Gram)

- PRADAN hired the services of an expert Agronomist in designing the field trials. The treatment plots were selected, based on consultation with plantation farmers and PRADAN staff. In all the plantation plots, plant (Tasar hosts) age varied between 12 months and 14 months.

- It was decided that the input and other costs required for the trials will be fully borne by PRADAN, from a project supported by the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India.

- The agronomic package of practices were finalized in late May. It was decided that Sesbania trial will be undertaken in 20 hectares in the 2nd half of June, followed by 60 hectares of Black Gram in late July and 40 hectares of Green Gram in August. Seeds of Sesbania were procured from a supplier in West Bengal. The remaining were organized locally.

- Rhizobium culture was recommended for seed treatment (Figure 5). The same was procured from local Krishi Vigyan Kendra, an extension unit of ICAR. Farmers were trained to carry out seed treatment with Rhizobium.

Figure 5: Farmers are trained in the seed treatment with Rhizobium.

- Soil was tilled with the help of a tractor. It required an average of 5 tractor hours to till the soil in 1 hectare of land.

- Rain came much later. There were very scanty rains (rain deficit >50% of the average) in June. Sesbania seeds were sown towards the end of June and beginning of July. Black Gram seeds were sown for an extended period starting from 15th July till 1st week of August. Green Gram seeds were sown in the 1st half of August. All the three crops faced major moisture stress owing to poor rainfall. Proper monsoon showers were received in the middle of September, before that rain was extremely sporadic and low.

- Identical plots were retained as control that received the common intercultural practices such as hoeing and organic manuring supplemented with Diammonium Phosphate (DAP) @ 50 g per plant.

- Poor rainfall affected the initial germination and growth of the crops. In certain plots, profusion of weeds was observed. However, with the arrival of normal rain in September, the crops outgrew the weeds and covered the ground.

- Sesbania was to be smothered in-situ at an age of 35 days (as the plants attain 2.5 feet height) and mixed with the soil. However, slow growth of the crop delayed the start of smothering operation to 9 weeks. By that time, there was profuse growth of nodules in the roots of Sesbania, proving a very healthy rate of nitrogen fixation by the plants (Figure 6).

- Sesbania plants were cut and mixed with the soil by using a rotavator that took 2 hours to complete the operation in a 1-hectare land area.

- Black Gram and moong crops were harvested by the plantation farmers (Figure 7). At the time of our visit to the villages, the crop was not fully harvested. The women were picking the pods manually. The harvest data thus could not be compiled.

- According to the villagers, the yield has been satisfactory. The area in Amarpur is so large (30 hectares) that it became difficult for the plantation farmers to manage the harvest. They have left it open to everyone. Apparently, any villagers could go and collect the moong pods from the field.

Measuring Tree Growth in the sites of Intercropping

On 10th November, 3 villages were visited namely Amarpur, Parsoti and Kerabari in Poraiyahat Block in order to assess the impact of intercropping on Tasar host trees (Figure 8). We had selected 5 out of 7 plots for taking data. The parameters were (i) Plant height, (ii) Plant girth at collar region and (iii) Plant girth at 1.5 ft above the ground. Data were gathered randomly from different parts of the field to minimize sampling error. The following table (Table 1) provides the sample size in each of the 3 villages:

Table 1: Overview of the samples across the three villages

| Sl | Village name | Crop-wise sample number | Control Samples | Total samples | ||

| Sesbania | Moong | Urad | ||||

| 1. | Amarpur | 12 | 10 | 0 | 12 | 34 |

| 2. | Parsoti | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| 3. | Kerabari | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| TOTAL: | 12 | 10 | 20 | 32 | 74 | |

Visual Observation:

- In Amarpur, the plants in Sesbania treatment sites showed remarkable growth both in terms of height and girth and are significantly different from the control plots. The leaf lamina of the plants in treatment plots were greener, smooth and were at least 1.5 times more compared to the control plants,

- The plant height and girth in the plots under Green Gram intercropping in Amarpur were conspicuously better compared to the plants in the control plots.

- Same trends were observed in Black Gram intercropped sites in Parsoti and Kerabari.

Statistical analysis: Parameters Plant Height and Plant Girth:

In the following tables (Table 2, 3 & 4), we are providing statistical analysis of the raw data gathered from the field to draw inference:

| Table 2: Parameter: Plant Height | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T | Df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Village | Treatment | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | |||||||||||||||||||

| Amarpur | Sesbania | 12 | 2.343 | 0.362 | 0.105 | 7.622 | 22 | 0.000 | 1.17667 | |||||||||||||||

| Control | 12 | 1.167 | 0.393 | 0.114 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Green Gram | 10 | 1.830 | 0.251 | 0.079 | 4.600 | 20 | 0.000 | 0.66333 | ||||||||||||||||

| Control | 12 | 1.167 | 0.393 | 0.114 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Parsoti | Black Gram | 10 | 2.264 | 0.323 | 0.102 | 3.565 | 18 | 0.002 | 0.65100 | |||||||||||||||

| Control | 10 | 1.613 | 0.479 | 0.151 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Kelabari | Black Gram | 10 | 2.162 | 0.253 | 0.080 | 9.839 | 18 | 0.000 | 0.94500 | |||||||||||||||

| Control | 10 | 1.217 | 0.168 | 0.053 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Table 3: Parameter: Plant girth at collar level (cm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T | Df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Village | Treatment | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | |||||||||||||||||||

| Amarpur | Sesbania | 12 | 13.417 | 4.144 | 1.196 | 4.928 | 22 | 0.000 | 6.83333 | |||||||||||||||

| Control | 12 | 6.583 | 2.429 | 0.701 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Green Gram | 10 | 13.700 | 2.263 | 0.716 | 3.506 | 20 | 0.002 | 3.78333 | ||||||||||||||||

| Control | 12 | 9.917 | 2.712 | 0.783 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Parsoti | Black Gram | 10 | 14.400 | 1.350 | 0.427 | 1.069 | 18 | 0.299 | 1.50000 | |||||||||||||||

| Control | 10 | 12.900 | 4.228 | 1.337 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Kerabari | Black Gram | 10 | 13.700 | 2.263 | 0.716 | 5.620 | 18 | 0.000 | 4.50000 | |||||||||||||||

| Control | 10 | 9.200 | 1.135 | 0.359 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Table 4: Parameter: Plant girth at 1.5 ft above ground (cm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Village | Treatment | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | |||||||||||||||||||

| Amarpur | Sesbania | 12 | 17.333 | 3.725 | 1.075 | 5.575 | 22 | 0.000 | 7.41667 | |||||||||||||||

| Control | 12 | 9.917 | 2.712 | 0.783 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Green Gram | 10 | 9.700 | 2.406 | 0.761 | 3.009 | 20 | 0.007 | 3.11667 | ||||||||||||||||

| Control | 12 | 6.583 | 2.429 | 0.701 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Parsoti | Black Gram | 10 | 10.700 | 1.337 | 0.423 | 1.557 | 18 | 0.137 | 1.60000 | |||||||||||||||

| Control | 10 | 9.100 | 2.961 | 0.936 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Kerabari | Black Gram | 10 | 10.400 | 1.647 | 0.521 | 4.657 | 18 | 0.000 | 2.90000 | |||||||||||||||

| Control | 10 | 7.500 | 1.080 | 0.342 | ||||||||||||||||||||

The statistical analysis validated visual observations. Intercropping has a significant positive impact on the overall growth of the plants. The mean difference in height varied from 55% (Parsoti Black Gram) to 100% (Amarpur Sesbania) vis-à-vis control. The most conspicuous difference in Plant Girth at the collar region could be seen in Sesbania intercropped fields. In Green Gram intercropped sites, the mean girth at collar region is thicker by 38% compared to the control. In Kerabari, the plant height and girth are higher and thicker by 78% and 49% respectively vis-à-vis the control.

To our understanding, Sesbania intercropping started in June, which means the effect of soil manipulation (through tillage), moisture absorption and nitrogen fixation is more prolonged with Sesbania compared to Green and Black Grams. Therefore, the impact of Sesbania intercropping is more pronounced as manifested through plant heights and girth thickness. For the local communities, the benefits received from the harvests of Green and Black Gram are most substantial / appreciable.

Cost Comparison: Intercropping and Conventional Alternative

We have considered the actual costs of various operations and the projected cost increases in the next 2 years. The cost comparison is between Intercropping and other conventional alternatives (increasing pit size, application of higher dose of manures etc.). The following table depicts the cost compilation for 3 years till the plants are fully established (Table 5). (After 3-years, the farmers will maintain the plantations from the revenue earned from silkworm rearing).

Table 5: Cost comparison between intercropping and conventional plantation.

| Intercropping

| Conventional Alternative | |||||

| Sl. | Practices | Cost Per Hectare (Rs.) | Sl. | Practices | Cost per Hectare (Rs.) | |

| A. | Year 1 | A. | Year 1 | |||

| A.1 | Pit digging- normal size | 10,962 | A.1 | Increased Size of Pits | 19,392 | |

| A.2 | Intercropping (Ploughing, seeds, labour etc.) | 9,500 | A.2 | Hoeing+ Increased Manure per pit | 14,544 | |

| B. | Year 2 | B. | Year 2 | |||

| B.1 | Intercropping | 10,500 | B.1 | Hoeing + Increased Manure per pit | 16,968 | |

| B.2 | Watering | 4,848 | ||||

| C. | Year 3 | C. | Year 3 | |||

| C.1 | Intercropping | 12,000 | C.1 | Hoeing + Increased Manure per Pit | 16,968 | |

| Total (Rs.): | 42,962 | Total (Rs.) | 72,720 | |||

The cost of treatment through intercropping in plantations is significantly less compared to the conventional alternatives. The Difference is (Rs.72,720 – Rs. 42,962=) Rs. 29,758 in a period of 3 years. This makes the unit costs of plantation raising more attractive for potential investors.

Impact of Intercropping on weed control and soil health

Intercropping with fast growing legume / pulse crops proved to be effective in limiting the weed growth. Initially, due to the poor rains, growth of the intercrops was affected and there were profusion of weeds in the plot. However, with rains, the growth in intercrops peaked to rapidly covering the ground and substantially outgrowing the weeds. Further as the crop residues were thrashed and mixed with the soil and left for decomposition in November, it is expected to further reduce weed population. The soil appears different; there has been an improvement in the texture, moisture content and friability. In certain patches, people have sown mustard in rabi, to use the residual moisture. However, this appears little ambitious, given the overall deficits in monsoon and first depleting water levels.

(We had collected soil samples from all the plots (treatment and control) for assessing Soil Organic Carbon, pH, Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potash and comparing the same with that of control plots. The test is being done at KVK, Godda District. The results are awaited).

Conclusion and Way Forward

- Integration of intercropping with plantations in degraded lands is beneficial on several counts:

- It triggers significant growth in the young plants thereby helping the plants to overcome stunting in young stages. After 3-years, the plants will grow on its own into full size,

- The practice of intercropping is far more cost effective compared to other conventional alternatives, therefore, its adoption will be faster among farmers and possibilities of investment will be higher,

- The overall plantation site undergoes positive changes; reduced weed growth, improved soil texture and better moisture retention.

- Intercropping, the way it is designed, is far less labour intensive, considering that the ploughing was done through mechanical means. Therefore, for smallholder farmers, who struggle to prioritize allocation of family labourers in agriculture and plantations (all major operations happen in monsoon season), it is easier to adopt intercropping in plantations rather than carrying out hoeing / manuring manually in large plantation plots.

- For marginalized households, gain from pulse grain harvests is much appreciated (Figure 9). This provided nutrition and cash earning to the household (we need to compile the harvest figures and assess the gains). This is important as Tasar host trees take 3-4 years to mature to host Tasar silkworms. In the interim, the farmers do look for some returns from the plantation plots that build their sense of ownership.

- Tasar host tree plantation raising is an established scheme among donors / investors, though the livelihood outcomes did not reach full potential. With the integration of Intercropping, plant growth will be significantly better. The same will increase predictability of higher income gains for the farmers on a sustainable basis, thus making it attractive both for the farmers (to deploy their lands for plantation) as also for donors / investors interested in livelihood impacts.

- It is planned to share the data with a number of stakeholders. PRADAN have been discussing the initiatives with the Central Silk Board, the apex sericulture institution in India. CSB is keen to undertake multiple locational research trials in their research stations.

- It is also planned to share the outcome of Intercropping in Tasar plantations with other mainstream agencies, positioning it as a potent model for restoration of degraded lands and generate sustainable livelihoods.

References

[1] Tasar silk is extracted from the cocoons of an indigenous silk insect called Antheraea mylitta Drury. Tasar silk worms eat the leaves of a range of tree species such as Terminalia arjuna, T. tomentosa and Lagerstroemia speciosa. These trees are abundantly available in the tropical sub-humid forests of India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Cambodia.

[2] Agricultural Land Use Statistics (2014-15, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmer Welfare, Government of India.

[3] In 1988, PRADAN had set up a project in erstwhile Bihar (now Jharkhand) to promote Tasar sericulture-based livelihoods for smallholder farm households, most of whom belong to Schedule Tribe (ST) and Other Backward Communities (OBCs). Tasar sericulture was a traditional vocation of the local communities, mainly the people living in forests and forest-fringe villages. Tasar silkworm was reared in certain host trees i.e. Terminalia arjuna, T. tomentosa that were available in the natural forests, managed by the Forest Departments. The silkworm rearers faced problems of accessing the host trees in the forest. The natural forests were in decline owing to poor maintenance and lack of tree replacements. These resulted to an overall decline of Tasar sericulture in the forests and loss of livelihoods of the local communities.