The world is reasonably aware of the scale of ongoing locust outbreaks (2019-20) in East Asia and West Africa, and the magnitude of its immediate impact. What needs to be improved is our understanding of how we got here; what could be the long-term effects; and what could be effective response strategies.

Locust invasions are stuff of nightmares. We know them from Abrahamic mythology as agents of God’s wrath, sent down from time-to-time as divine punishment for human sins. Even the less theological view of locusts is based in fear, evoked partly by the unpredictability of swarm invasions, and partly by the lack of response options when they arrive.

Contrary to this impression, desert locust outbreaks (albeit smaller than the 2019-20 ones) are fairly common over about 20% of the earth’s surface, occurring almost every year in desert areas across North Africa, the Middle East region, and southwestern Asia. There is an extensive Early Warning and mitigation systems in place, spanning hotspot countries and managed by various regional Desert Locust commissions supported by FAO.

The recent outbreaks are certainly rare for the size of the swarms, the area covered, and the damage caused; leaving more than 40 million people in a state of severe food insecurity in 3 regions (the last comparable (but smaller) infestation was in West Africa in 2003-05). They were triggered by 2 episodes of heavy rains in the vast deserts areas of the Arabian Peninsula known as ‘The Empty Quarters.’ Brought about by cyclones Mekunu (May 2018) and Luban (October 2018), these rains filled spaces between sand dunes to create ephemeral lakes, creating conditions ideal for desert locusts to breed and multiply into large numbers. These cyclones, their trajectories, and their specific effects were freak events; and led to unprecedented growth in the number of locusts that overwhelmed existing early warning and mitigation systems.

So the causes of the ongoing crisis are well understood. And while it is difficult to predict the next perfect storm that will recreate the perfect locust breeding conditions, if cyclones become more and more frequent (as they have been for the past 6 years), there will be more desert locust upsurges. Especially in East Africa.

So how do we prepare? Discussions at the 1st Virtual Practitioners Conference on Desert Locust Management (August 10, 2020) threw up some key ideas to build resilience to locusts around.

Strengthening, upscaling existing early warning and mitigation systems

As mentioned earlier, there are early warning and mitigation systems in place in ‘frontline countries’ (with desert areas that serve as breeding ground for locusts). These systems comprise of satellite-based tools that monitor locust populations, as well as manpower in the form of ‘prospectors’ who spend months in desert areas exterminating hopper colonies before they take wings. These systems need to be scaled up and their capacities strengthened so they can cover the possibility of increased outbreaks in the future.

To target such resources better, use can be made of data and mathematical modelling. Promising work is being done in this regards by the International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe), who have developed models to predict new locust breeding grounds in East Africa, based on data (biophysical and bioclimatic) from other parts of the continent. Such data from Africa is found in abundance, in databases like WaPOR. So there is much scope for applying their models and produce useful intelligence to service Early Warning systems and targeting of efforts to eliminate locust colonies at nascent stages. Read/ watch more about this here

Tracking and Fighting Swarms

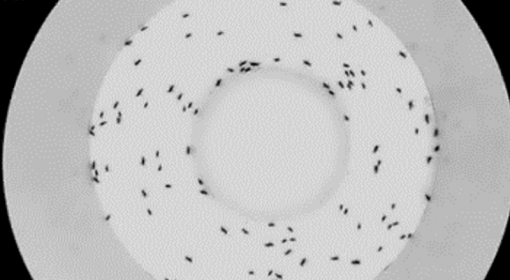

As important as satellite data tracking rainfall, vegetation, soil moisture, and other indicators determining ideal locust breeding grounds; is ground-level data tracking hopper bands and swarms. Technology— most notably the survey app eLocust3 made available by the FAO for wide use– is an essential aid to such data collection. A big idea in this area is engage in such survey communities in affected areas, like how OXFAM is doing in Kenya. Their work has shown that with some training, farmers and pastoralists can fan out in large numbers and survey their area to collect data locating locusts. Such crowdsourced data has high resolution, and can prove invaluable to providing early warning to communities further down the locusts’ flightpaths.

Pesticides continue to be the main pushback against advancing swarms. Beyond a certain swarm strength, chemical fertilizers are the only viable option given their quick kill time. However, their negative impact on the environment and non-target species can be limited significantly by targeting hopper bands and nascent swarms with biopesticides. Use of biopesticides is already being widely promoted. The ones currently in use are based on fungi spores with mineral oils (diesel/kerosene) as solvent. Environmental impact can be further reduced by using biopesticides based in essential (plant) oils. A team of scientists from University Graz has developed prototypes that are ready for field testing.

Here is a novel idea for fighting back against locusts: catch them and feed them to chickens. This is precisely what has been tried out in parts of Pakistan with some success. Local communities were encouraged to catch locusts at night (when they are not flying but resting on the ground), and sell them to poultry feed manufacturers. The insects make for a good, protein-rich feed. On average, 1 community in Punjab province was able to catch 7 tonnes of locust per night, and individuals could make about 120 dollars for one night’s catch upon selling it off. This way, the swarm was contained, while creating livelihood opportunities.

Building back better: regenerative agriculture

Links have been made between human activities and the intensity of locust outbreaks. Intensive agricultural practices degrade soil quality, reducing nitrogen content in the soil and protein content in the crops that grow in it. Such crops have a higher carbohydrate content, which locusts like and thrive on (they need these carbs to fly hundreds of kilometres as they can do in one day). Further, overgrazed lands create bare patches that allow locusts to lay eggs. Conversion of wooded land to open fields (such as grazing land) is known to encourage locusts too.

Much of these insights come from work by the Global Locust Initiative. They highlight yet another facet of sustainability and resilience offered by regenerative agricultural and land use practices—that value rehabilitation of natural resources as much as exploiting them. They cannot be adopted as a quick fix against future locust outbreaks. They should be seen as a paradigm that boosts overall resilience to all manners of shocks.