By Meghna Mukherjee (MetaMeta), Ishan Agarwal (FES), Saheb Bhattacharya (PRADAN)

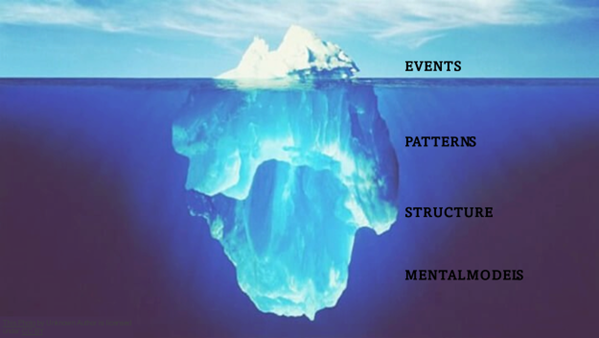

One of the most common approaches to address challenges is to react based on what is visible. For example, if there is less water available in any structure: the solution is more often than not to build more water harvesting structures. However, when we dig deeper and understand the layers, we know the trends and the reasons which influence those trends. Digging deeper allows us to peel additional layers to understand the beliefs, customs, and norms of why events happen in a particular manner.

To facilitate the understanding of what is beneath the pile of layers, researchers/practitioners, and policymakers rely on using the Iceberg Model. The Iceberg Model was developed in the 1970s by anthropologist Edward T. Hall to understand society’s visible and invisible components. Today, the Iceberg Model is considered one of the most powerful tools for systems thinking by looking into what created the situation in the first place.

Using systems thinking to understand the agricultural sector in India

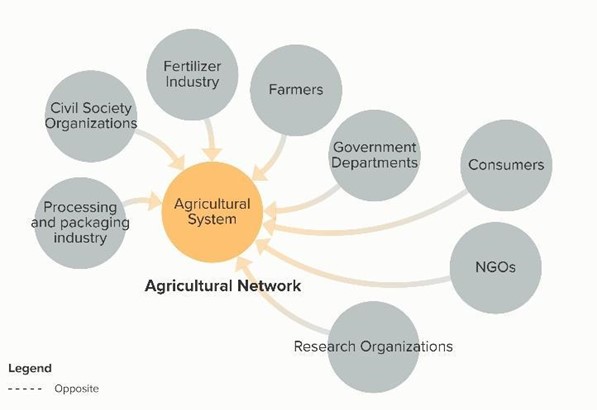

When we talk about agricultural systems, we must see and recognize the different components that constitute the system. Let’s start by identifying the various components of a farming system. Farmers (prominent!) are one of the system’s many parts. The other members include consumers, government at different levels (from local to national), research organizations, processing, distributing, and packaging companies, the fertilizer industry, civil society organizations, and NGOs, to name a few. All these different components interact with each other and thus form a network. Any change in parts will have implications for the whole network.

Let’s take, for example, changes in the prices of fertilizers brought by the Central Government of India. One of the most prominent policies has been the rollout of fertilizer subsidies to encourage farmers to use them for better productivity. This is a lucrative opportunity for the fertilizer industry as an incentive from the government starts large-scale production of fertilizers. Farmers buy more fertilizers as the prices are low, thus enhancing their productivity. The research organizations, NGOs, and civil society try to understand the impacts of chemical fertilizers on consumers and find alternative ways of achieving the same yield level with better management of resources.

Using the iceberg Model

Now that we understand systems thinking, it is appropriate to see how the iceberg model can aid in understanding the system. We used the iceberg model to understand the working of the agricultural extension workers in the state of Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh in India. It was seen that the agricultural extension workers needed to perform their job more effectively. During a discussion with women farmers in the Santhal Pargana district of Jharkhand, they explained that they had never met the Kisan Mitra (agricultural extension worker). Kisan Mitra aims to promote sustainable livelihoods for medium, small and marginal farmers by improving the last-mile delivery of farm support services. It is operated through volunteers, Farmer Collectives, NGOs, Entrepreneurs, and Field Staff.

Usually, the Kisan Mitras are blamed, and interventions are developed to expand their capacities. Additionally, women farmers would be considered as not knowing the farming system; hence activities to promote their knowledge would be undertaken.

However, the Iceberg Model suggests that the inefficient functioning of agricultural extension workers is only an event that is visible to us. But what is invisible is where the answer to this problem lies. If we understood why last-mile service delivery persons fail to do their job, we could be in a better position to address the issue.

After discussing the issues with government officials belonging to the village and block level across different departments in Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh, the shortage of human resources is a serious issue. In many areas, Krishi Mitras have yet to be hired, and the organizational structure only facilitates hiring in some places. Additionally, many block-level officials have been managing the role and responsibilities of various positions. This translated to ineffective monitoring systems, thus needing full attention to the functioning and work of the service delivery persons. While interacting with government officers, the lack of funds was highlighted, which adversely impacts the officers’ functioning, especially those who are at the last mile.

Digging deeper, we can analyze the structures that result in human resource shortages. Literature suggests that admission to different positions at the government level is difficult. There is a series of examinations that one needs to qualify for before they are appointed. Many people are unaware of the tests; the vacancy list and lack of information create gaps. The bureaucracy in government jobs does not make it easier to find employment. In the case of Krishi Mitra, it has been found that, more often than not, the positions are filled through networks and connections. It leads to more autonomy and less accountability by the KMs, leading to inefficient functioning.

In some cases, mindsets and mental models also play an essential role. Women farmers complain about KM’s unavailability and lack of awareness and information about schemes. During an interview with one of the Krishi Mitra, he explained that since women are not considered farmers, the information channel does not reach them. However, their husbands and sons interact with KMs and are aware of the system’s working.

Way forward

There is no direct, linear, and simple solution to address such problems. Iceberg Models help us identify the reasons, which are deep below. As practitioners, we should be mindful of the existing patterns, structures, and mindsets that can influence the system’s working. We must pay heed to such lessons and understand that visible things should not be considered, but efforts should also be made to understand the invisible forces.