A case for social water productivity

Here is a main question. If water is one of your main assets, by who and for who is the asset used and who is benefitting from the use of this asset? Does the added value leave the rural area, even leave the country or does it go the hands of local farmers – who may circulate it in their local economy. Who get what part of the value created? How is the water productivity socially distributed? These are important questions, but often they are not asked.

By looking into social water productivity we may see the choices that are often not made explicitly yet that have a major bearing on the population. When the Songuroi farm was first planned in in Narok and Bomet counties in Kenya, the model was that of an estate farm that would cater to the rising international demand for avocados. There was however considerable local resistance, there was not much free land available for the export farm and also local water resources would be dedicated to a single business with little local linkages. On the other hand horticulture development offer so much opportunities for poverty alleviation. It already account for almost 9% of the GDP of Kenya and providing almost 6 million jobs directly and indirectly. Many of these are women who make up 75% of the labour force in small scale agriculture and manage 40% of the farms, Horticulture in Kenya is also a fast-growing sector, registering a growth of 15% annually against 6% for the agricultural sector as a whole.

Faced with these challenges the plan for the farm was changed from an estate to a nucleus farm. The nucleus farm would produce approximately 30% of the avocados, destined for a supermarket chain in Europe. The balance was to be produced by 500 small holders living in a radius of 25 kilometres from the nucleus farm.\

In the end Introduced avocado as a new commercial farm enterprise for 560 smallholders out growers farmers and a large plantation along the Mara River in Narok and Bomet. Before the project, Songuroi farm was piloting avocado production, and was not connected to the smallholders, who were loosely organised in several self-help groups of 20-30 farmers. Baseline household income of farmers per months is KSh 3000-5000, depending the project sub-areas, which was earned from maize, cabbage, tomato, kale and beans. The change from an estate to the out growers farm ensured that a large part of the water productivity remained in the area.

Another case on social water productivity is the Ingahusai project in the Ica region in south western part of Peru. The project was designed to produce high value crops such as grapes and asparagus for export in the coastal region of the country. The project would need around 300 Mm3 of water annually and water from the highland areas which was used by subsistence farmers was to be diverted to the coastal areas to meet the water demand of the project. This was a reasonable approach by the government as the use of water for production of high value crops such as grapes and asparagus would bring more revenue and would create more jobs in the area. Monetarily speaking, asparagus production would bring 8900 dollars per hectare while production of subsistence crops in the highlands would only bring 470 dollars per hectare. Water productivity would increase 20 fold if water was diverted to the coastal area rather than being used in the highlands. On face value, the project seemed to be the best use of the water as it would maximize the value of water.

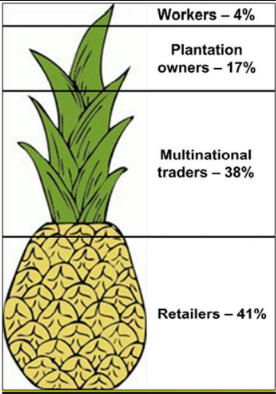

But a closer look at how benefits would be distributed in society revealed a different story. Research shows that only 4% of the revenue produced from production of high value export goods trickles down to farmers (see figure 1). The majority of the benefit goes to retailers and investors. To put this in perspective; 1000 m3 of water used for subsistence farming in the highlands would bring farmers 180 USD. On the other hand, 1000 m3 of water in the coastal area generates a net revenue of 935 USD. Out of this revenue only 75 USD would go to farmers and plantation workers which is less than half of what they would have earned under subsistence farming. Under the seemingly “more productive” coastal investment farmers would lose their share of water and end up worse off than they were under subsistence farming.

This is a very good example of how on face value water productivity could increase without creating any social benefit. Social water productivity or “pro-poor water productivity” aims at increasing the value of economic value produced for the very poor in society and balancing the income inequality. It aims to enhance not just monetary value of water but social benefits of water as well.

This blog is based on the works of Dr. Jeroen vos from Wageningen University on Social water productivity and a business case on out grower Avocado growing scheme developed by Solidaridad, Hivos and SNV.

This case is prepared as part of the Water-PiP (Water Productivity in Practice) Program. Water-PIP aims to support a 25% water productivity on the ground. For ideas and suggestions on improved water productivity, please contact t.uyttendaele@un-ihe.org or lknoop@metameta.nl