Posted by Frank van Steenbergen

May 06, 2014

As cities grow the challenges of finding safe water grow with them. And so goes the story of Amsterdam – the capital of the Netherlands. As the city expanded, it tapped into a reliable source – the water from nearby coastal sand dunes. In 1853, the water supply lines from the dunes to the city were commissioned. The dune water was better than any water in the city: it was clean with no pathogens – filtered in the sand – and the taste was pleasant.

However, thirty years later, signs of limits being reached appeared: because of heavy pumping water tables in the coastal zone started to gradually go down. Problems turned nasty from 1925. Sea water started to intrude into coastal aquifers and salt water was ‘upconing’ – meaning that saline water under fresh water lenses in the dunes were increasingly pulled upwards, spoiling the city water supply and making it brackish. To add to the woes, the delicate dune ecology – the major sea flood defense in the Netherlands – started to change.

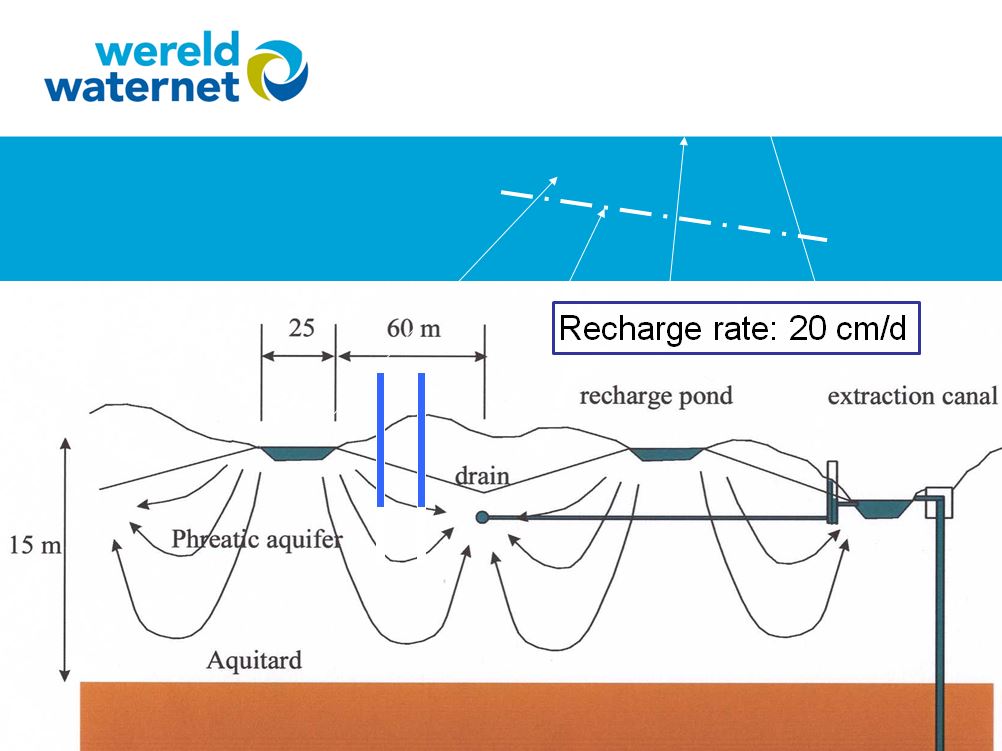

In 1955 things were turned around by the development of a large so-called artificial recharge system. In artificial recharge, surface water (from rivers for instance or from storm water or treated waste water) is caused to infiltrate and add to the groundwater supplies.

In case of Amsterdam water from the River Rhine was transferred from a navigation canal to the dune area through a 65-kilometer pipeline. In the dune area the water is spread over an area of 36km2 with 9 km of open basins, from where it gradually infiltrates into the dune sand. It is then intercepted by drains which lead the water to huge storage ponds. From there it is treated through (among others) aeration, slow sand filtration and pelleting; and then sent to the city.

Prior to being lifted to the dune areas the river water is pre-treated. If this was not done the basin might fill up with algae and the dune sands would be polluted with heavy metals and others. The dune system improves the water quality but clearly does not replace the treatment of water. In case of the Amsterdam Dune Water Machine, pre-treatment consists of coagulation (to get rid of nitrates and phosphorus), sedimentation and rapid sand filtration.

The Dune Water Machine was switched on in 1957. It has been working ever since and according to its operators from Amsterdam Waternet it is meant to do so for another 1000 years. The Leiduinen system provides 60% of the water to 700,000 inhabitants of Amsterdam and the numerous businesses in this economic hub. It produces 600,000 cubic meters of safe water a day. It has also pushed back the seawater intrusion. The Amsterdam system is not the only artificial recharge system. Similar systems can be found all along the dune area in The Netherlands.

Artificial recharge has great potential to quench the demand of an urbanizing world. By creating reliable groundwater reserves, high quality water is available and a strategic reserve is built up that can deal with droughts and other calamities. In many cases there is a natural match between protection of the water resource, nature conservation in the recharge area and creating possibilities for green recreation. There are many ways to carry out artificial recharge –only dunes will not do – but water can also be stored in the sandy banks of rivers or in karstic aquifers.

{Jcomments on}