By MID-P NGO

This blog is part of a dossier on locally-led adaptation, featuring insights and lessons from the Reversing the Flow (RtF) program. RtF empowers communities in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan to build climate resilience through direct funding and a community-driven, landscape approach.

The Ewaso Ng’iro River weaves life through the hot, dusty, and arid landscapes of Isiolo County, Kenya, where communities are rewriting what it truly means to make decisions to thrive as a community. Under RtF, decision-making has a living experiment in trust, community conversation, transparency, and accountability.

From July 2025, communities living along River Ewaso Ng’iro in Isiolo took bold steps toward leading an inclusive development process through a series of participatory landscape-level conversations facilitated by Merti Integrated Development Programme (MID-P) in partnership with MetaMeta and the County Government of Isiolo.

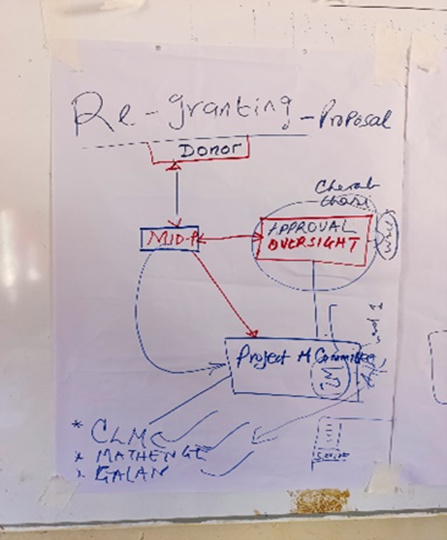

Across Cherab, Chari, and Sericho Wards, villagers gathered (including elders, women, youth, and administrators) to confront their shared challenges: flooding, rangeland degradation, and fragile governance systems. From these community conversations, a three-tier regranting structure emerged, a carefully negotiated framework placing power squarely in community hands with two community committees (Landscape and Cluster Committees) and the Project Implementing entity.

Landscape Committee

- Comprising of Visionary community leaders

- Provide landscape leadership

- Carriers of the Landscape Vision

- Does the overall landscape coordination

- Allocates resources to community projects through the proposals from cluster committees.

- Resolves and Manages Project disputes and misunderstandings.

Cluster Committee- (Chari, Cherab and South Clusters)

- Coordinate ward and village level deliberations and activities.

- Proposal development in partnerships with their communities

- Monitoring project implementations

Project Implementing entities are either existing community structures like the Community Land Management Committees (CLMCs), School Committees, the Grazing committees, water project committees or the ad hoc non registered at times even not yet formed community structures like the Merti floods Committee etc. The implementation entities are to receive the grants and implement the agreed projects.

The Complexity of Local Decision-Making: In August 2025, the operationalization of the re-granting model/process was to kick off but the Cherab Cluster Committee challenged the initially agreed re-granting model which did not allow transfer of grants to either the Landscape committee or the cluster committee but had direct funds transfer from MID-P to the project implementing entities.

Due to lack of an existing cluster wide flood control community structure, the Cherab Cluster Committee members preferred to turn to be an implementing entity. This raised a lot of concerns from the community members and the ad hoc Merti Flood Committee representatives. This led to Merti Floods Committee writing to MID-P stopping the funds regranting process till all community fears and concerns were addressed.

A joint meeting was convened on 2nd September 2025 with participation of MID-P team, Merti Flood Committee, representatives of Landscape Committee, the Cherab Cluster committee and chief from Merti representing the government administration. Merti Flood Committee members raised their concerns with keen reference to the Locally Led Principles expressing their mastery of the river and with ongoing similar initiatives already in the river. Re-assessment of the river would just be a waste of time and resource since the Merti Flood Committee already them. The initially agreed re-granting model was referred to by community members present as well

The disagreements led to a remarkable act of civic participation: a community letter formally requesting that earlier agreements be upheld. It was an expression of accountability from the grassroots, a signal that the community was owning both the process and the principles behind it.

The long, and emotional discussions marked by bitter exchanges ended up with a compromise: the Cherab Flood Community Organization was to be formed with representatives from all the villages of Cherab.

As one participant put it, “Disagreements are part of progress. What matters is that we resolve them together and remain focused on our shared goals.”

Lessons: The Power and Patience of Local Leadership

Decision-making, especially when it involves resources, is never easy. It requires countless conversations, revisiting agreements, and sometimes even reversing decisions. But this “slow” decision-making is precisely what builds trust, accountability, and legitimacy. It demonstrates that being locally led is not about speed, it’s about depth, ownership, and shared responsibility.

Across Isiolo’s landscape, this process has become a lesson in democratic patience: communities learning that leadership is not about control, but about collective stewardship. The back-and-forth, the letters, and the re-negotiations are a proof that power is truly shifting to the people.

Living the Spirit of “One Landscape, One Voice, One People”

What emerged from Isiolo’s a movement that values listening over dictating, compromise over conflict, and inclusion over imposition. It shows that locally led development is not a slogan but a practice that demands time, humility, and courage to let communities decide their own path, even when it means rethinking earlier choices.

When communities argue, deliberate, and finally agree together, they are not just managing projects; they are building the foundations of collective resilience. That is the true meaning of decision-making under locally led principles, messy, slow, but deeply transformative.