Authors: Clara Nieuwenhuyse, Frank van Steenbergen

Visualize a rice paddy field: peaceful, lush green, with rice plants swaying gracefully in the wind. But make no mistake: within this peaceful picture, there is a relentless battle going on, placing farmers against tiny assailants, sometimes hardly visible to the naked eye. Insects, weeds, aphids and diseases may ravage the crop that farmers do their best to protect, often using chemical pesticides. However, – besides being harmful – the indiscriminately used pesticides can, over time, produce the opposite effect to that intended by inducing resistance in the target organisms. Alternative methods exist and have become more common as the set of practices known as Integrated Pest Management (IPM). In IPM strategies, chemical pesticides are used as a last resort when other options are ineffective. Let’s take a look at what IPM has to offer:

Cultural practices for effective prevention measures

The first strategy in the battle is to establish a preventive context against the arrival of the assailant. Cultivation practices must therefore be carefully chosen, consisting of managing the land by regular weeding, cleaning the bunds, and destroying the nursery leftovers. “Prevention is better than cure”, as the saying goes, but such measures are all the more important to consider as they do not consist exclusively of a preventive approach, but also of biological control. Harvesting must be carried out close to ground level to destroy the pests comfortably hidden in the stubbles and expose those that remain to the birds, which are farmers’ great allies in this case. Plowing is recommended to expose and eradicate pest larvae. In addition to field management, cropping patterns also have the potential to reduce pest injury by modifying ecological conditions and varying the seeding and transplanting dates, which disrupts the pest establishment in the cropping system.

Biological control via natural habitat management

To stack all the odds in their favour, farmers need to surround themselves with powerful allies: this is known as biological control, or the use of specific organisms to combat others that are considered undesirable. Given that the main natural enemies of pests are spiders, drynids, water bugs, mirid bugs, damsel flies, dragonflies, etc., providing them with a suitable environment by taking good care of their habitat is essential. Biological control can also be achieved by increasing the ecosystemic complexity of rice fields: incorporating fish, frogs, or ducks is a helpful strategy for controlling pests and weeds and has proven promising in various countries such as China, Japan, Vietnam or the Philippines. Fishes like grass carp feed on young weeds, while frogs prey on larvae and insect nymphs. One adult bullfrog can eat more than 100 insects a day. Ducks eat both pests and young weeds, and provide droppings that contribute to the fields fertilization. Pest control is then ensured, in addition to environmental benefits provided to the field ecosystem and added economic value. A potential win-win-win situation, in other words.

Mechanical practices to remove infected plant parts

Mechanical measures are a classic that never disappoints, giving you a direct grip on things. Rice seedlings tips can be clipped at the transplanting time to decrease the transfer of pests from the seedbed to the transplanted field. However, those manual techniques are often laborious and time-consuming, although effective.

Traps to attract and kill pests

Aside from those categories, pest-killing lamps and light traps can control pests based on their attraction to light. The lamps are calibrated in specific ranges of wavelengths and frequencies of light. High voltage wires ultimately electrocute the pests, which fall into a collecting bag.

Biopesticides for an environmentally-safe pest control

Biopesticides are substances derived from natural materials or living organisms (such as fungi and bacteria) to control pests growth or incidence. Biopesticides have the advantage of being environmentally safe compared to their synthetic chemical counterparts, due to their reduced persistence in the environment and greater host specificity. When necessary, preference should be given to biological control substances before considering synthetic chemical pesticides.

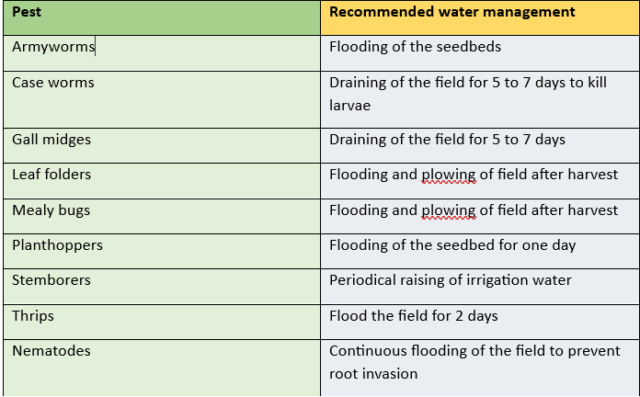

The new element: pest control through water management

There is one element that so far was missing in the IPM repertoire: field water management. Pests may occur because the land is too wet or too dry at the wrong time of the year. Not everyone likes water in the same way. Some organisms can’t stand water at all, while others do not thrive in dry environments. Knowing their respective weaknesses can help determine the adequate water regime to adopt to fight them. Water management can then be adjusted to counter certain pests as prevention or control measures by ensuring flooding or draining of the fields at a particular time of the crop growing cycle.

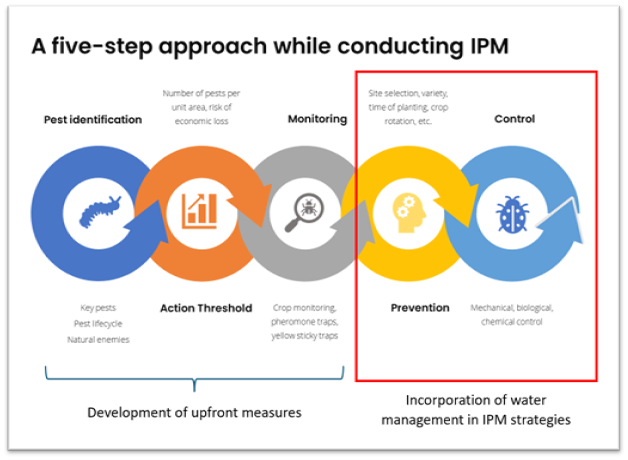

While the tireless fight against pests has traditionally been waged with chemical means, innovative, cost-effective, environmentally friendly, and healthy techniques for farmers are emerging. Chemical control is used within the framework of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) when it is carried out in a targeted manner, at a precise time, and with a rotation of the products used to prevent pests from developing resistance. The innovative nature of IPM lies in the possibility of combining these techniques, and systems are better managed when prudence is ensured by diversifying prevention and control measures.

Water management is linked to pest incidence, yet IPM strategies usually do not entail specific recommendations in this regard. This is an additional and promising management measure. Balanced strategies relying on multiple aspects of the production system are necessary, and incorporating natural resources management within IPM strategies could prove advantageous. In other words, it is likely that no single measure exists as an isolated solution for effective and environmentally friendly pest management. The key would then be to ensure rigorous monitoring, assessment of the ecological relationships, resources available, and aim to achieve. Caution must be established by relying on preventive and control strategies when needed. Now that you have those insights make sure that next time you see a rice paddy, you take a fresh and curious look to acknowledge the parties involved in this landscape of relative peace!

References:

Basnet, P., Dhital, R., & Rakshit, A. (2022). Biopesticides: a genetics, genomics, and molecular biology perspective. Biopesticides, 107-116.

Huang, S., Wang, L., Liu, L., Fu, Q., & Zhu, D. (2014). Nonchemical pest control in China rice: a review. Agronomy for sustainable development, 34, 275-291.

IRRI (International Rice Research Institute) (n.d.). https://www.irri.org/

Prakash, A., Bentur, J. S., Prasad, M. S., Tanwar, R. K., Sharma, O. P., Bhagat, S., … & Jeyakumar, P. (2014). Integrated pest management for rice. National Centre for Integrated Pest Management, New Delhi, India, 43.

Sihdu, C. (2023, March 3). Integrated pest management (IPM): managing crops with natural solutions. PlantwisePlus Blog. https://blog.plantwise.org/2022/06/21/integrated-pest-management-ipm-managing-crops-with-natural-solutions/

Sow, S., & Ranjan, S. (2020). Integration of Azolla and Fish in Rice-Duck Farming System