by Frank van Steenbergen

January 15, 2019

Whatever progress happens on the surface, statistics are harrowing. Ethiopia is still an epicentre of malnutrition. Though figures have improved over the last 15 years, UNICEF Global Databases on Infant and Young Child Feeding show that about 38% and 10% of Ethiopian children under five years of age are stunted and wasted, respectively. Among children between 5 and 19 years old, 36% of girls and 22% of boys are underweight. On top of overall malnutrition come nutrient deficiencies: Iron Deficiency Anaemia (IDA), Vitamin A Deficiency (VAD), and Iodine Deficiency Disorder (IDD).

There is also an iron-clad chain here: a vicious intergenerational circle. A malnourished mother will give birth to a low birth-weight baby, the low-weight baby will grow as a malnourished child, then to a malnourished teenager, then to a malnourished pregnant woman, and so the circle continues. Poor nutritional status of women both before and during pregnancy results in children being underweight when they are born. Malnutrition goes beyond physical health. It is related to poor school performance and low productivity of individuals. Malnutrition reduces children’s ability to learn, think, and become creative.

| Wasting, or thinness, is an indicator of acute (short-term) malnutrition. Wasting is usually the result of recent food insecurity, infection, or acute illness such as diarrhoea. Measurement of wasting or thinness is often used to assess the severity of an emergency, with severe wasting being strongly linked with the death of a child. Stunting, or shortness, is an indicator of chronic (long-term) malnutrition. It is often associated with poor development during childhood and is one of the harmful effects of poverty. Stunting is commonly used as an indicator of development, as it is strongly related to poverty. Underweightness is an indicator of both acute and chronic malnutrition. Underweightness is a highly useful indicator when examining nutritional trends. |

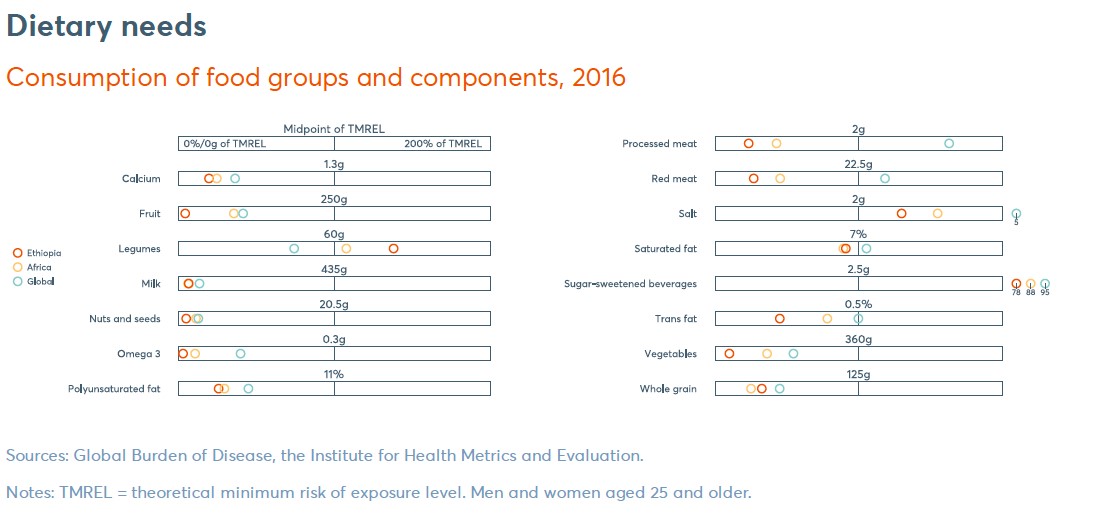

Poor diets might be due to insufficient food, or a lack of variety of foods, infrequent meals, insufficient breastmilk, and early weaning. Malnutrition is not the single consequence of a single factor but a mixture of different causes: inadequate care of children and women; poor health services; too many children in a family to feed; food shortage due to small land sizes, low productivity, landlessness (especially among young families) and spending on non-essential things like khat (on the rise), beer (on the rise) or cigarettes. The composition of the diet is also a major factor. In Ethiopia, look at the figures of the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation: even compared to the rest of Africa, the intake of fruit and vegetables is extremely low. The same is true for essential nutrients such as Calcium or Omega 3.

In all of this is a huge paradox. In spite of all the shortages, there are plenty of opportunities. Many Ethiopian villages are nutrition deserts, but they should not be. Unlike Asian villages, there are no home gardens. There is no cultivation of vegetables or trees around the houses that could make a difference in sourcing food, nutrition, or medicine. Similarly, there is not much village poultry. They are strangely missing from the landscape, and there is a strong case to change this and develop homestead gardens that provide food that feeds the body and mind.

Vitamin B, Vitamin E, and Vitamin K, Omegas 3, minerals like zinc and chromium, all boost health and cognitive power. One gets them from nuts and seeds, small red beans, eggs, kale, and certain tree crops. These are available in Ethiopia, but are not part of the courtyard activities. Kale is a special one – common in Ethiopian food – providing more than the daily requirement for vitamins K, A, and C; as well as Omega 3; and minerals like potassium, copper, and manganese, fibe and Omega 3. Eggs are important providers of vitamins B6 and B12, folate, and choline (63). Choline is an important micronutrient that helps regulate mood and memory. Nuts (including peanuts) and seeds are good sources of vitamin E, which helps cognitive capability. Moringa, the superfood tree, occurs in many parts of Ethiopia but is not standard in households. Its nutritious leaves increase spatial memory, are highly nutritious, and anti-inflammatory. Avocado is another good contender. It is rich in monounsaturated fat, which contributes to healthy blood flow and is good for all organs, including the brain. Then there are fountains of Vitamin C that could do a lot of good: papaya and vegetables.

There is a strong case to fill the empty courtyards and schoolyards and tackle malnutrition at the source. Creating such health gardens needs a concerted effort – a change in awareness, skills, and mindset. It has been done in other countries in cooperation between the government and communities. It can be done in Ethiopia as well.

{jcomments on}