by Usman Qazi

In a relentless pursuit of growth and development, the Pakistani state has ignored colonial-era strategies—that took natural risks, like monsoon floods, into consideration.

The Indus River is unique in more ways than one. If we ignore this, we do so at our own peril. In the last three decades, or more, the Pakistani state has been putting aside concerns for the uniqueness of our river, and relentlessly pursuing multi-billion rupee constructions, endangering existing infrastructure and the lives of our people.

Colonial-era designers were more aware of such natural forces, planning with and around them to prevent the sort of floods we have seen over the last three years. The Pakistani state has not only ignored, but worked against some of the colonial-era planning that helped the British avoid the devastation that we see today.

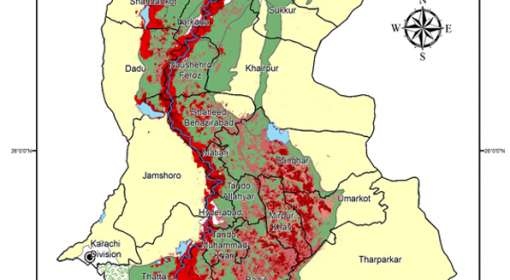

Water flows at incredibly different speeds through the River Indus—anywhere between a few thousand, to millions of cubic feet per second (or cusecs). Colonial era designers of the Indus Basin Irrigation System (IBIS)—the largest contiguous irrigation system in the world—were well aware of these huge fluctuations in water flows from one monsoon season to the next. Since the IBIS was primarily built on the left bank of the river (the east of the Indus River, if you look at an average map), it meant that the right bank (or the west of the river) was empty. There was a reason for this. The right bank sat between the Suleiman mountain range, and the Indus. And that meant that there was less land to irrigate. And that the area needed to be mostly free, so that water flowing from the Suleiman mountains could wash out in the Indus.

This right bank was not just useful to deal with water from the Suleiman mountains. It was also useful to deal with the excess water from the Indus River during monsoon seasons. The British officially picked parts of the right bank, and designated them as “breaching sections” in various land use plans. A “breaching section” was meant to be blown up if authorities feared that the water pressure on the other side of the river may breach the protection infrastructure and jeopardise the canal infrastructure. The geographical depressions in the area between the right bank and the mountain range would hold the excess water and the embankments would be repaired after the Monsoon season.

For this reason, no major infrastructure was developed on the right bank in these breaches. Special relief funds were routinely allocated to alleviate the inconvenience of people who would be evacuated from the areas and affected by the controlled breaches.

Pakistan’s policy shift

In 1976, technical and safety considerations gave way to political expediency. The Pakistani state started to violate land use plans that would govern the application of lands on both sides of the Indus River. Instead, the state started to construct a number of mega infrastructure schemes, chiefly the Chashma Right Bank Canal and the Indus Highway. Naturally these developments have spawned permanent human settlements, businesses and community infrastructure in areas that the British would earlier call flood-prone.

In the colonial era, the British had a plan for how to deal with excess flood water—they would declare areas, on the left bank in Sindh and right bank in Punjab, as breaching sections. Now, when the flood water becomes too overwhelming for the embankments to contain, irrigation managers are faced with the choice of imperilling either the intricate canal system on one bank, or the equally vital newly constructed assets on the other.

With the violation and seemingly irreversible changes of the land use plans, the old rules and protocols about blowing up the officially designated breaching sections in the event of a flood have become redundant—and no new rules are being put in place.

This has given rise to a culture of might-is-right with the more powerful and influential sections of society asserting their prowess to stop embankments breaches where they see it imperilling the assets belonging to themselves or their supporters. This open playing field translated into water breaking the embankments and other lines of flood protection on the right bank of the Indus River downstream of the Guddu barrage near Kashmore, and during the 2010 floods—submerging areas that would not have been inundated under British land use plans and flood management protocols.

Usman Qazi is an engineer, and a community development, human rights and humanitarian relief worker from Quetta, Balochistan.

This article originally appeared on www.tanqeed.org

Related Link: Videos related to ‘Pakistan Floods’ on TheWaterChannel