Even as you read this, more than 12 million people struggle to cope with the worst effects of the famine in the Horn of Africa. More than 500,000 people have had to flee to refugee camps. The UN has warned that over 300,000 children are severely malnourished and “in imminent risk of dying.” And we are yet to hit rock bottom: the famine continues to spread and threatens to engulf the whole of Somalia.

Even as you read this, more than 12 million people struggle to cope with the worst effects of the famine in the Horn of Africa. More than 500,000 people have had to flee to refugee camps. The UN has warned that over 300,000 children are severely malnourished and “in imminent risk of dying.” And we are yet to hit rock bottom: the famine continues to spread and threatens to engulf the whole of Somalia.

While few anticipated the magnitude of the crisis, food insecurity has afflicted the region for a long time now. Over the years, the International Aid/ Development community has expended much time and focus on activities designed to address the issue. That a famine of this magnitude could still strike the Horn shows that we need to rethink our strategies.

So far, the famine has been reported largely in terms of the magnitude of its effects, the number of victims and the emergency relief required/ mobilised. And understandably so, for this is the immediate task at hand, and a formidable one at that.

However…

“If donors, development agencies and governments do not attend to the medium and long term, this kind of tragedy will happen again,” said IFAD Vice President Yukiko Omura, at a recent emergency meeting on the issue, at the FAO in Rome. “We must think not only about saving lives today, but build sustainable livelihoods to avoid future calamities,” said Jacques Diouf, the FAO president.

The UN estimates that about $2.5 billion in aid is required to meet the current crisis. Almost 50% of this requirement remains unmet so far. The recent economic crises have much to do with the reluctance of governments and the public to pledge more. However, it also reflects a lack of confidence in the effectiveness of international aid to East Africa so far.

Diouf suggested that the lack of results might be down to the fact that we’ve been focussing on the wrong areas. “What the world is seeing now is the unfortunate result of three decades of underinvestment in agriculture and underdevelopment,” he said.

The region’s food-economy is built on small-scale farming, which is the main source of livelihoods and resilience to shocks. “We cannot control droughts, but we can control hunger. To do so we must invest in the world’s smallholder farmers so that they can feed their communities and their families,” said Omura.

| {hwdvs-player}id=1029|height=240|width=320|tpl=lightbox|thumb_width=130{/hwdvs-player} | As we look for long-term solutions, we must look at Ethiopia. Over the years, a common-sensical focus on soil/ water conservation and planned land/water-use has defined its agricultural policy. This has improved agricultural productivity and led to greater food security. In some regions such as the northern Tigray, watershed-level soil/water conservation has had very visible effects on farmers’ livelihoods and incomes. So much so that they now spend their own time and money on planning & carrying out such activities. |

(Click the picture to play the video ‘Land, Water and Livelihoods: The Watershed Movement in Tigray’)

Besides, Vinod Thomas of The World Bank’s Independent Evaluation Group points out, the government has been increasing investment in irrigation development, and in improving farmers’ access to weather forecasting systems.

Of course, there is much left to achieve in Ethiopia, with many of its regions still in the grip of drought and thousands of people on the move in search of relief. However, there has been a significant improvement over the past 20 years. Tigray used to be a basket case of food-scarcity; it is now one of the areas least-affected by the ongoing famine.

We need to figure out what lessons can be drawn from the Ethiopian example, for other countries in the region. But before that, there is another question that needs to be answered: while the immediate relief operations are of utmost importance, when would be a good time to start building long-term resilience?

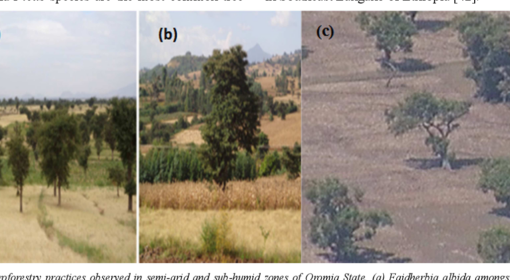

(Image courtesy: Lakew Desta, Bahi Dar University, Ethiopia)