Girma Senbeta (MetaMeta Ethiopia), Getachew Engdayehu (Amhara Bureau of Agriculture), Nardos Masresha (MetaMeta Ethiopia), Guta Eshata Gemmechu (MetaMeta Ethiopia), Bantamlak Wondmnow (Amhara Bureau of Agriculture), Redeat Daniel (MetaMeta Ethiopia), Getanew Tesfaw (MetaMeta Ethiopia), Tena Gobena (Oromia Bureau of Agriculture), Mitiku Bajiga (Ethiopian Ministry of Agriculture), Frank van Steenbergen (MetaMeta), and Jean Marc Pace, Femke van Woesik (MetaMeta)

Imagine a large tanker sailing across the ocean. If you alter the ship’s course by just one degree at the beginning of the journey, the final destination can differ by hundreds of kilometres. In other words, over time, a small change can make a huge difference. This was the intention of the Green Future Farming (GFF) program: a small engine propelling a vast vessel onto a new course.

Ethiopian governance has a large and strong agricultural department with a far-reaching extension system, which is a key policy instrument for necessary changes. Over the past four years, GFF has worked together with the Bureaus of Agriculture in Amhara and Oromia on the transition towards regenerative agriculture, restored landscapes, and a more vibrant rural economy. In this blog, we want to share the essence of this journey and the lessons we’ve learned.

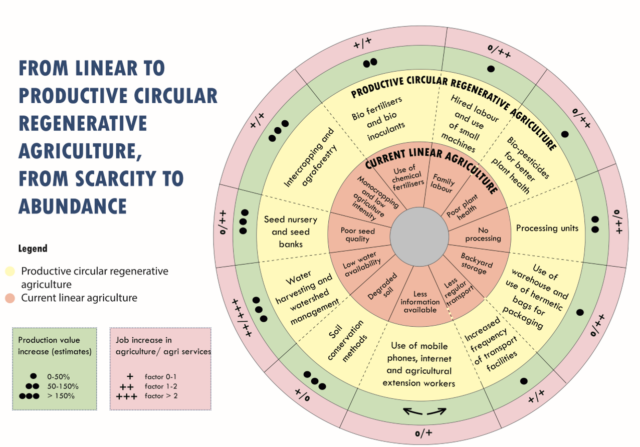

We worked along the cycle of regenerative practices (figure 1). At every step in the farming system, there is scope to do better—less degenerative, with better yields and more income opportunities. We aim to foster the transition of linear agriculture towards productive circular agriculture with better cropping systems, seeds, tools, healthier soils, safe pest and rodent control, storage, rural transport, and local climates.

Figure 1 – Transition from linear to productive circular agriculture

Particularly in rural Ethiopia’s land-scarce context, the farming systems can be expanded by complementary non-land-based activities, such as beekeeping or homestead poultry. These regenerative practices, deeply rooted in local services and inputs, open new avenues for job creation in agriculture and associated services. By doing so, regenerative agriculture acts as a catalyst for invigorating the rural economy and offering aspirational livelihood opportunities, particularly for the youth and women.

GFF has explored the options for regenerative agriculture and better resource management in these partly conflict-affected areas. Throughout this journey, the program has collected much practical experience and insights into the various facets of regenerative agriculture and circular local economies through exploration, implementation, and experimentation. These findings, lessons learned, and recommendations are also collected in a blog bundle through blogs written by the diverse group of individuals working on the GFF program in Ethiopia.

Here we share with you the six main learnings:

1 | The path to a greener future is more than regenerative agriculture

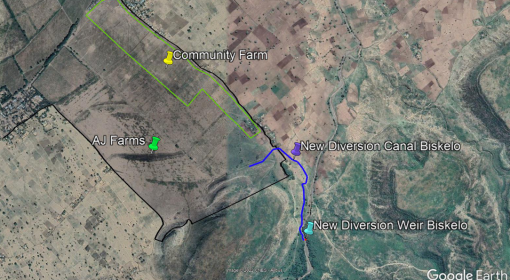

Securing sustainable agricultural inputs, improving farming practices, and implementing interventions that restore the landscapes are essential but are not the entire puzzle of the transition towards a greener and better future. Local economic development, improved transport and road connection, and market access are also essential. Together, they form the building blocks required for transition in rural areas. This means that within GFF, we tried to address all the puzzle pieces, see the bigger picture, and connect the dots to form a cohesive strategy for rural transformation.

2 | Livelihood development requires a holistic approach

Securing livelihoods is essential for the transition towards regenerative agriculture and restored landscapes. Establishing alternative livelihoods next to farming is not only necessary to secure inputs required for regenerative agriculture systems, such as biofertilizers and vermicompost; it is also the core to strong, vibrant rural economies that can bring positive future outlook for rural communities. Supporting Small Micro Enterprises required a holistic and bottom-up approach. It goes beyond mere financial support: social dynamics are equally important. The potential is huge, and further scaling of the revolving fund can catalyze rural livelihood development.

| “Our kebele is not familiar with beekeeping. As a result, the majority of farmers were first uninterested in this work. A conflict of interest also existed. My neighbors warned me not to introduce bees because they would attack our kids and cattle. I made the decision to assume any danger in relation to the fear they expressed. I tried using local beehives to create before, but it didn’t work out. The GFF program provided me with training and transitional beehives. I began my endeavor with beekeeping by moving the colony from the neighborhood hive to a new one. Because the bees didn’t create an abundance of honey at the appropriate time last year, I didn’t harvest enough honey. However, I gathered three rounds this year and sold them for over 20,000ETB. Some of my neighbors consider this to be a miracle because it exceeds their expectations. I wish to have more bee hives, and beekeeping will become my regular task in the future.” – A farmer from the Oromia region |

3 | Community participation and participatory land use planning is essential for restoring landscapes and creating buffered microclimates

Restoring landscapes and creating buffered microclimates requires a bottom-up, community-central approach, whereby participatory land use planning is essential. This not only raises awareness and community ownership, but incorporating local knowledge in planning also increases the success rate of the interventions.

4 | Stakeholders’ engagement and strengthening local level institutions is key for sustainability

| “In many ways, these initiatives have benefited our rural community, particularly women and youth. These practices are critical for increasing productivity and rural incomes and strengthening and diversifying the rural economy. The Oromia Bureau of Agriculture is ready to scale up the program’s best practices at the kebele, woreda, zonal, and regional levels by sharing the lessons learned through documentation, workshops, and more. We aim to extend the geographic scope and transfer successful approaches across the region through program-trained individuals that provide technical training and share experiences as resource persons in the regions.” – Tena Gobena, Senior Natural Resources Expert at the Oromia Bureau of Agriculture |

GFF is more than a four-year program. It is a new approach to agriculture, livelihood, and landscapes for rural Ethiopia. This approach was solidified through the active engagement of stakeholders and the strengthening of local-level institutions. By disseminating our findings, documents, and training materials in local languages via printed bundles and USB sticks through established agricultural offices from the Ministry of Agriculture, we ensured the program’s legacy could endure despite challenges such as the high turnover of leaders and officials.

Working within the locally established institutional context also allowed for faster scaling and amplification of the program’s success. The project was handed over to the legally organized entity known as community watershed users’ cooperatives. This transition sets the stage for further scaling up successful interventions across the wider community. Another example of this is the take up of the vermicomposting activities by the local government and their efforts in establishing vermicomposting centers that allow the activity to scale. Also, private sector partnerships are essential for long-term sustainability, for example, in the construction of this Gabion Check Dam.

5 | Program adaptability is essential.

Facing challenges like regional conflicts taught us how crucial it is for a program like GFF to be resilient and adaptable to the urgent needs of the communities. One unexpected lesson was the importance of providing psychosocial support, something we hadn’t planned for at the start but became essential due to the conflicts. Program flexibility in implementation is thus essential to respond to the actual situation on the ground rater than sticking to a rigid plan. Strategies and interventions should be adjusted based on Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning results to better serve the communities’ immediate and changing needs.

6 | Regenerative agriculture is very relevant in times of conflict and crisis.

A large part of the implementation period of GFF was marked by open conflict and severe civil disturbance, with Gubalafto woreda being in the war zone for several months and Middle Awash being the scene of severe disturbance. Contrary to what one would expect, it made improved regenerative agriculture in high demand. One reason is that relying on local resources to make essential agricultural inputs was a lifeline strategy in the disturbed situation. This explains the high interest in producing bio-fertilizers when chemical fertilizers came out of reach because of high prices and disturbed supply lines. It also proved to be more effective and affordable. The second reason is that regenerative practices provide a window to rebuilt lives and household economies after the onslaught of war. This was the experience from the program whereby women were trained in homestead poultry and provided with chicks and equipment to do so. This was more than a livelihood intervention; it also helped to look upwards and move away from trauma. This was reinforced with informal coffee ceremony meetings in which painful war experiences and lessons on how to manage the homestead poultry were shared.

Finally, a lesson not only from GFF but from other experiences in MetaMeta is that exactly in time of conflict, the idea and prospect of development is important to bolster hope.

| ‘’Just after we have been through the traumatic state of conflict; by the virtue of GFF support I had the opportunity to receive a practical step by step training on holistic household poultry farming and provided with start-up twenty five day 45 old chicks and improved feed. Following I managed it well along with continuous follow up from Office of Agriculture. By now; in addition to continuing my chicken farming, from the sale of eggs and laying-off chicken, I have assets of seven sheep from out of nothing;. And I am also anticipating owning a dairy cow so that my children drink milk like their neighbours do’’ – Ms Yeshi Abera (Project beneficiary) |

As we progress, the lessons learned and the strategies developed serve as a blueprint for sustainable rural development. The GFF program’s journey shows the potential of regenerative agriculture to improve the environment and agricultural productivity and uplift entire communities, providing them with the tools and knowledge to sustain these gains into the future.

Our collective vision for a greener, more prosperous Ethiopia remains strong, and we are committed to continuing our efforts inspired by the resilience of the Ethiopian rural communities.

This program was supported by IkeaFoundation.