Somaliland: the camelback is broken

By James Firebrace and Frank van Steenbergen

March 16, 2017

Famished camels cross barren landscape near Ballanbaal, late Nov 2016

In an area dependent on thin and fragile rainfall disaster has arrived: drought, massive loss of livestock, just a straw away from famine. In the canon of the United Nations arid Somaliland officially does not exist. It is a self-declared independent country in the Horn of Africa that broke away from the chaos of “Mogadishu’ in 1991. Somaliland is still not recognized by any other nation. Clearly different from the rest of Somalia, however, it has been a miracle of peace and is not plagued by the terrorism of main Somalia in the Southeast. Though it has managed its politics and economy amazingly well, it is now at the harsh receiving end of one of the most devastating droughts in recent memory, affecting the entire region but coming down in full weight in the eastern part of its territory.

Here, in the eastern part of Somaliland the 2016 Deyr (September to November) rains almost entirely failed, except for limited patches. This followed on three years of very erratic or poor rains, which has depleted the resilience of the area. The continued drought led to large scale loss of livestock (50% to 100% in the areas visited), desperate population movements in search of pasture, and a gripping shortage of water for humans and animals alike. With their only resource base gone, people are at the mercy of famine and it now just takes a straw to literally break the camelbacks. Old people claim this is the worst drought in living memory in a country that is often on at knife edge and has learned to cope with. It has led to a devastated pastoral economy and a population of 2.5 Million at risk. There is an urgent need to avoid mass displacement and the resulting long term dependency and undermining of the cohesive fabric of Somali life.

Left: Dried up water point on Mt Shimbiris; middle: Group of women waiting for rations at El ’Aaro; right: Dead sheep, one of many thousands, in termite mound landscape on way to Owdale. All pictures are taken late November 2016.

Disaster foretold? Yes and no. The crisis was hidden for a long time for a sad and bizarre reason. Whilst the drought was unfolding, it was not picked up by increasingly sophisticated international satellite monitoring and early warning systems. This has led to a severe under-estimation of the crisis already enveloping this area.The FSNAU Food Security Outlook to May 2017 gave a misleading picture showing the region only categorised as IPC2 (“Stressed”), with only some parts of the region moving to IPC3 (“Crisis”) after February 2017. Bizarrely, the latest Early Warning Early Action indicator showed some of the worst hit areas in Sanaag and a large part of Sool as ‘Not in Alarm Phase’. The Somali Drought Watch in December 2016 updated the picture and came with a better assessment, yet may still missing out some of the most troubled spots. The truth on the ground unfortunately was entirely different.

In November-December 2016, James Firebrace visited the Eastern Somaliland on the request of Somaliland’s Presidency and National Drought Committee. People were taking their increasingly weak and depleted herds to remote areas where they expected some pasture and water but when arriving there found overgrazed areas and found themselves trapped with animals too weak to move back. This is what it was like in November – three months ago, at the end of the failed rainy season and at the start of the real dry season.

“There is no water in this area, no wells or shallow water. Even if our animals could eat this vegetation there is nowhere to water them ”. Abdulahi, pastoralist met in vicinity of Owdale.

“I have no option but to stay in this area. My remaining animals are too weak to move. If I stay here at least we have the chance to pick up water from passing water tankers”. Pastoralist in area where people were laying thorny branches across the road in the hope that water tankers would stop and fill up their hand-dug water holes.

“We had a large herd of 400 animals, now we have just these 20 left. Both our transport camels have died. We are taking away these three jerricans (20 litres each) and that must last us for the next three days. It is enough for cooking and drinking only. We only wash when we come here (the water distribution point) and we must do our daily religious ablutions using sand not water”. Zeinab, carrying her two-year-old child Abdulrashid.

“We have 30 berkads (water reservoirs) in this immediate area, but all but a couple are now entirely empty”. Resident of Hagira (Xageera), on the way to Waridaad.

“In this village we are already hosting an extra 12 families. This is beginning to create strains for both hosts and guests alike. This is the case for all the villages in this area”. Interview in Berkad Ali Hirsi.

“Our remaining animals are too thin and diseased. They cannot be sold and there is barely any meat left on them. We burn our dead animals to get rid of the odour, to stop the spread of disease and to deter hyenas”. Faarah Hassan Suleyman, Qa’ab.

“I remember the Daba Dheer drought and lost many livestock then. Before that I remember the Sig’aas drought when I took all my animals to Erigavo and lost half of them. And before that again, when only a boy, I remember a terrible drought when the British were here but before the Italians arrived (i.e. before 1942). But of all these, this is the most serious. This drought has taken in all our grazing lands, while in earlier ones there was always some pasture left somewhere.” Saleh Kaar Faarah, old man in his 80s near El ‘Aaro.

“I came from Derqa near Garaadag. We made our way down to the Hawd. We have now lost all but a few of our livestock and are walking back to save what we can ”. Woman pastoralist met at Qoorlugud.

“Some call this drought Sima (the Equaliser), we could also call it ‘Isunkeene’ (Bringing Together), as so many clans are now in this place, from east, west and south, all now living together.” Saleh Warsame from Dadhere, NE of Waridad, waiting for water and rations at El ‘Aaro

“Most worrying was the situation of people ‘on the road’, either still trying to make their way south with their remaining livestock in very poor condition, or in some cases, if they had already lost most or all their animals, trying to make their way back to Saraar. Both these groups were badly in need of water and food. Looking ahead, it seems likely that these movement will slow and stop, as people realise that their safest bet i Qoorlugud is the first watering hole (many shallow wells of muddy saline water) that can be reached south of the main road. Many hundreds of animals in poor condition are now here, with attempts being made to keep herds separate to stop the spread of disease. This is becoming a significant problem. Camels here were in poor condition with little left by way of hump (their fat store) and with their ribs showing. Because of their extreme poor condition – often looking little more than just skin and bone, these animals are worthless and unsellable in local markets, even if they could be taken there”. James Firebrace himself.

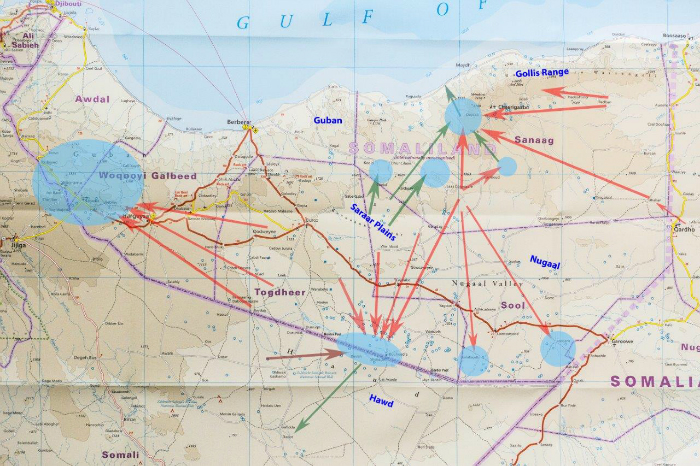

Map showing main displacements of pastoralism during the course of this Deyr (based on interviews with pastoralists)

Blue circles show areas that had some rain. Red arrows show the main directions of movement,

brown is early movements, green is later movements. Base map used: Horn of Africa 1:1.8m, World Mapping Project.

Read also the full report of James Firebrace “The Hidden Crisis in Eastern Somaliland“

{jcomments on}