Thomas Hoerz, Area Manager Somaliland, Welthungerhilfe

Hargesia, November 11, 2021

Looking at the larger picture – the international climate change regime – some questions cannot be ignored: are we pressing the right buttons in climate mitigation? Are we investing where we have most CO2 impact? Are we looking at impacts beyond sequestered metric tons in terms of social and economic impacts? How is biodiversity affected and what do sequestered metric tons of CO2 do to the water tables? In Somaliland, like in many African dryland areas, such questions affect tens of millions among the rural population.

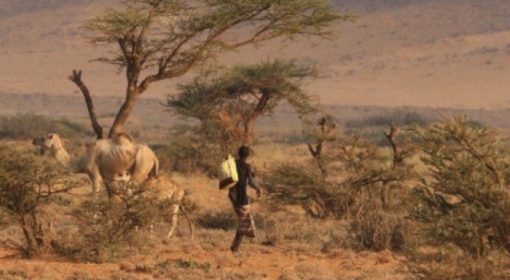

While industrialised countries are considering investing billions in nuclear power, which could provide CO2 -free electricity in 10-20 years, village communities in Somaliland and many other countries in the dry zones of Africa are beginning to fight hunger with natural and immediately effective measures. The fact that millions of tons of CO2 are permanently stored in root biomass is of little concern to them. Their problems are more tangible and life-threatening now: a rapidly progressing destruction of the natural vegetation due to poor pasture management, charcoal extraction and more frequent, prolonged droughts that are depriving their sheep, goats and camels of fodder and thus the pastoralists of their livelihood. The unprotected soils are eroding faster and faster, and a possible recovery of vegetation is becoming increasingly unlikely and protracted. Due to reduced infiltration of water, springs dry up and groundwater levels sink to inaccessible depths. There are now thousands of families who spend half their income on water, delivered by tanker trucks from over 50 km away.

In discussions with affected communities – which in Somaliland are basically all of them – the core statements about the problem are repeated: If we cannot secure the water and fodder basis for our animals, we will have to leave our areas. Agriculture is not an alternative – rainfall is too low, irrigation is too expensive or impossible. Charcoal production destroys our fodder trees, but it is often the only way to secure income now. Large-scale protection from deforestation and overgrazing takes land out of use, which initially reduces income for years.

For Welthungerhilfe, this initially looked like an unsolvable equation. Can impoverished communities be expected to make high sacrifices for achieving long-term ecological and economic goals? What is feasible with the limited resources of an NGO? Fences were considered, which would require investments of millions with a high conflict potential. Also considered were tree plantations with a high risk of failure in the absence of rain, alternative incomes and resettlement. The solutions that are now proving to be feasible are much more obvious, cost-effective and can be implemented in smaller steps than we dared to hope. They rely on the drive of those affected, on the regenerative power of nature and on the limited resources and technical knowledge from outside.

Clear agreements on what we want to achieve on which areas

A series of events in the village identifies the most pressing problems of pasture, water sources and livestock, and which developments in these areas that are likely to occur in the mid and long term. An inventory of the village’s ‘assets’ is made. Generally this is the labour force, knowledge of the vegetation, topography and tenure of each area and the needs of the grazing animals. Welthungerhilfe sets out its options: financial possibilities, technical knowledge, the networking of experiences from other areas and the possibility of mobilising governmental and international aid. In the end, there is a contract declaring an initially small area, 20-200 ha, as a protected area and what measures will be taken together. Signatories are, besides the representatives of the village, the Ministry of Environment and Welthungerhilfe.

A bundle of measures for more food, more water, more climate resilience and income

At the beginning there is the question of protection of the designated area. This is only possible if the protected area clearly belongs to a village community. This is confirmed by all neighbouring villages. The community commits to the protection measures and the sanctions for transgression in public meetings and names responsible persons to enforce the penalties. This includes even the rural police forces.

The lost income is not immediately compensated by cash transfers or food aid, but by cash-for-work to build simple dry-stone walls and ditches to keep water and soils in the protected area. This secures income while accelerating the recovery of vegetation. The planting of grass and tree seeds or seedlings also helps. Technical trainings for beekeeping are conducted and simple modern beehives provided. The protected vegetation multiplies the harvest of honey, an expensive and sought-after product in Somaliland.

In the medium term, grass harvesting can be started cautiously as early as the third year and after seed shedding. Grazing can start in later years, in times of need, to ensure the survival of animals. Wells can be dug in the lower-lying zones of the protected area that provide water for longer months or even all year round. In many cases, Welthungerhilfe can set up a solar pumping station, which can then supply the village directly with clean drinking water. At the moment, over 1,000 ha are protected and used in this way by 12 communities. Without exception, all communities have asked for support to expand these areas.

What 1,000 ha of protected areas in Somaliland mean for the world and climate change

At first, almost nothing. 5,000 tons of stored CO2 per year costs about 150,000 USD, which is about the same as the CO2 price in Europe. Only this money does not arrive in Somaliland, the procedures are too complicated. While these figures are irrelevant for the participating villages, the climate world should ask itself some self-critical questions.

- How do we evaluate CO2 storage or savings that are only made possible with minimal investments and without “CO2 investments,” versus those that only show a positive CO2 balance after years or decades? Can we consider E-mobility, dams, wind turbines, nuclear power plants? Can the absence of an ‘investment dip’ be rewarded?

- How do we value 5,000 tons of stored CO2, which reduces poverty, provides water, protects crops and roads and promotes biodiversity? Can storage with only positive effects, without any ‘risks and side effects’ be measured and rewarded differently?

- What does area protection and the recovery of natural vegetation mean in view of the fact that almost half of the global land area consists of arid areas that are not or only partially suitable for agriculture? Doesn’t animal production as biological-organic pastoralism in drylands have to be evaluated completely differently than industrialized farming?

- Does the current fixation on the tropical rainforest as the ultimate climate savior need to be reconsidered?

- Why are measures that combat poverty in a climate-friendly way and preserve biodiversity not promoted more strongly – especially in areas that are particularly affected by impoverishment and rural exodus?

What to do to harvest low-hanging fruits and level the playing field

The fixation on one key figure ‘tons of CO2 ‘ must be reconsidered and certainly overcome. The question must also be asked: what are the social, economic, ecological and cultural side effects of storage or saving?

Drylands, in particular those that are pastorally managed, have a clear comparative advantage here (something new, normally pastoral areas tend to be characterised by comparative disadvantages). The higher proportion of roots alone (60-80% of the total biomass) and the soil depth at which roots are formed mean that carbon is stored longer and more reliably. We have discussed the positive side effects (from the point of view of those affected, these are of course main effects) above.

For these reasons, we should multiply the number of tons of carbon saved or sequestered by a factor that increases or decreases their total value for people and the environment, depending on the speed, amount of CO2 investment, permanence and all side effects, both positive and negative. We believe that area protection in drylands would clearly do better than mega-investments in centralised power plants, e-cars or industrial ‘CO2 hoovers’. Where drylands cannot compete– they will not be able to sell expensive high-tech products, they will not promote the steel-, cement-, electronics- and plastic industry and they will not make the industrialized societies richer.

The 20 billion Euros that a nuclear power plant costs, and after planning and repayment of CO2 investments, could protect 27 million ha and enhance vegetation, store 675 million tons of carbon and ensure a dignified life for 9 million pastoralists. Now, not 20 years from now.