Symbiosis: Pastoralists and Farmers in Balochistan

by Allah Bakhsh and Frank van Steenbergen

April 21, 2020

There is a narrative that the competition between pastoralist and farmers in arid areas is a sure route to conflict, and there are many examples that illustrate this – from Darfur in Sudan to Afar and Issa in Ethiopia. Yet this need not be so. Relations between pastoralist and farmers can be just as well symbiotic, mutually beneficial, and relatively peaceful. This the story from Balochistan – Pakistan’s large arid western-most Province.

Livestock is important in Balochistan: 72% of its population earns part of their living by rearing animals and selling milk, wool, and butter. Nomadic pastoralism – mainly with small ruminants – is widespread. There are two major types of geographies in the arid Province: lowlands and highlands. Lowlands get rains but even more importantly short term ‘spate’ floods in the summer months. The rangeland then gets greener and animal fodder is grown, catering to the livestock needs from July to February every year. On the other hand, highlands get snowfall in winter, from Mid Oct to Mid-March every year. The rangelands in the highland ecology then get greener Mid-March onward. In both geographies, when fodder is available, livestock herders stay in their respective areas.

In general, lowland livestock keepers do not migrate to other areas, but try to feed their animals on local grasses and stored fodder. They only migrate when there is a long dry spell when fodder and stockwater become very scarce. In such times, flock owners and economically poor households migrate to the irrigation canal areas of Sindh and Punjab Province, seeking employment opportunities as labourers. Normally, the local host communities do not like their presence since they have large numbers of livestock themselves that need grazing grounds too. There is also tension between migrants and local farm owners when animals enter cropped fields. Such livestock migration, however, only occurs during exceptional dry years.

For highland livestock owners the patterns is entirely different. In Balochistan the two major tribal groups—the Baloch and the Pashtuns– each have their own distinct areas consisting of plains and mountains. Nomadic groups from both ethnic groups in of Balochistan and some from adjoining areas in Afghanistan migrate every year in search of fodder in winter months. At that time their own landscape is cold and barren and even covered with snow, which creates a shortage of green fodder. The transhumance annual migration also protects humans from the cold, as most people live in makeshift tents. Groups from each tribes go into areas where their own languages are spoken. Several passage routes bring Baloch nomads from the highlands (called Khorasan) to the lowlands and back, such as Bolan, Sukleji, Kashuk, Mula and Karkh. Migration starts from mid-August when they start walking with their flocks, household items, and families. They make halts and feed their animals in the rangeland along their routes. Normally they complete their travel in 15-30 days. Those who can afford send ahead family members and household articles by trucks.

Nomads passing Karkh valley enter Shahdad Kot district in Sindh, passing Sukleji and Mula in district Jhal Magsi. Nomads coming to Sibi, Bolan, Dhadar, Bhag travel through Bolan Pass and settle in the local areas and its neighborhoods. What attracts them there are the vast spate flood-irrigated areas of the Kacchi Plain, which includes Bhag Nari, Sibi, Sunni, Lehri and Jhal Magsi. The pastoralists decide where to stay during the winter period depending on the abundance of the spate-irrigated crops. This may differ from year-to-year as cultivation depends on the presence of unpredictable flood flows – unpredictable in quantity, timing and the ability to manage. Pastoralists find out which area is the best through their links with the local communities, who provide them intelligence on the cropped areas and villages. Sometimes, a member from each of the pastoralist families visits the area ahead of others and scouts it before others arrive.

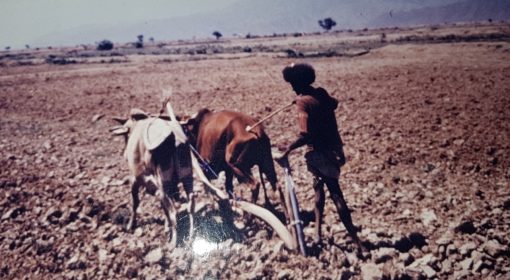

The area under spate irrigation in the Kacchi Plains is upwards of 100,000 ha. Sorghum, guar (cluster bean) and pulses are the main crops. Local farmers welcome nomads to their lands since they bring prosperity, because they buy the standing crops in large volumes. Upon arrival the nomads first settle their camp outside the cultivated land or in empty places within the cultivated areas. Since they have been coming for several years, they usually know the farmers and the lands very well. Upon arrival they typically go on a transect walk to the sorghum fields, which are mixed with mong and mooth beans crop. They make their own assessment of the production, contact the land owner, and offer their prices against the fields they select.

Once the deal is done, the charge of the field is handed over completely to the nomads until after the harvest. Upon taking the control of cultivated fields they move around, collecting weak plants, and thinning strands that are particularly dense (to feed to their animal back in the camp). Similarly, there are always some wild grass and plants species that are also uprooted and used as green fodder.

Pulses ripen earlier than sorghum. So, the pastoralists collect them and place them on a small pile inside the standing sorghum fields to let them dry. Once the pulses have half-dried, they bring them near the camp to dry them further under the sunlight. Later, in November-December, they thresh the pulse to separate grains and chaff. The grains are immediately taken to the market for sale; the proceeds are used to make the first payment to the land owners. They start feeding the chaff to their animals when they come back home at the end of the day. During the day a male family member grazes the flock in nearby plains which contains less fodder, till the peak winter approaches.

Next is the sorghum harvest. The panicles are carefully harvested by hand by men and women and then similarly left to dry under the sun. After threshing, the grains are taken to the market for sale and the final payment to the land owner is made. Back in the field, sorghum stalks are still standing with dry leaf. The animals are allowed to feast on these. In addition, much of the stalks are chopped in small segments for use as feed stock. The harvesting is done in stages with animals moving from one harvested field to another.

Not all local farmers or tenants sell their crops to nomads. Some have their own cattle at home and need their own fodder for animals. In such cases the common arrangement is that the harvested sorghum fodder is taken by the tenant families but they give 1/8th of the stems to the land owner. The land owner owns all the stubbles. These are then sold to the pastoralist nomads who buy the grazing rights of stubbles and crop residues. In such fields there are always wild grasses and green bushes that can be fed to the animals.

There is much respect between the two communities. Nomads always follow the built roads while passing through villages or cropped lands with their animals, with a number of guards in the back and front to keep animal away from straying into the cultivated fields. They use stagnant water in depressions that are found either in deepest part of the field, or left over in channels, or in nearby village reservoirs. Generally, pastoralists are regarded as very polite people by the sedentary farmers, as they are guests in the area and they do not want to ruin their relationship with the locals. They do not get involved in theft and prevent any disturbances that their animals might cause. They use the local market of nearby villages or towns for their daily needs. They sell their animals in local livestock markets to generate the cash they need to meet their daily needs.

After the big annual fair in the Kacchi Plains, the Sibi Mela in February or March, the pastoralists bid farewell to the local farmers and return to the highlands. This relationship is truly symbiotic and peaceful.

{jcomments on}