By Guta Eshatu

Vermiculture (stemming from the Latin word ‘vermis’, meaning worms) uses earthworms to transform organic waste into high-quality compost, called vermicompost, full of beneficial microorganisms vital for healthy plant growth. This process enriches the soil with essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium and improves its overall quality, making it more fertile and conducive to crop growth. A thriving soil microbial population is essential for a resilient agricultural ecosystem (Azarmi et al., 2009; Dhakal, 2013).

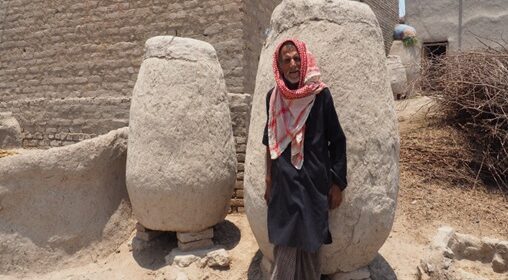

The Green Future Farming (GFF) project aimed to showcase the benefits of vermiculture through hands-on demonstrations in the Arsi zone (Oromia, Ethiopia), specifically in the Diksis, Sire, and Jeju areas. The project adopted an innovative approach using a particular composting bin to produce solid vermicompost and compost tea. These bins were constructed with the help of local carpenters, using readily available Eucalyptus wood, ensuring that they were both practical and suitable for the needs of local farmers.

Involving farmers directly in the construction of these bins was a strategic move to make the technology more accessible and to instill a sense of ownership and familiarity with vermiculture practices. The ultimate goal of the GFF project was to encourage the adoption of vermiculture among farmers in these communities. The initiative was met with enthusiasm, particularly in Diksis and Sire, where farmers quickly began to see the benefits of integrating vermicompost into their agricultural practices, signaling a successful step towards sustainable farming.

There were some earlier vermiculture initiatives, but these missed the mark on showing just how much vermicompost could boost crop yields. Farmers often did not know the best ways to feed the worms or understand the full benefits of using vermicompost in their fields. There was a clear need to get vermiculture on everyone’s radar and highlight its potential. The GFF project did this by getting farmers directly involved and teaching them how to build their composting bins and start vermiculture by mixing the worms’ feed into those bins. The project also organized detailed training sessions and workshops that brought everyone from local farmers to government officials into the conversation.

This approach paid off. The government took notice and even set aside funds for building vermiculture centres across the Arsi zone to rear the worms required for the vermiculture practices. Each woreda received a budget of 4.5 million Ethiopian Birr, and ten centres have already been built and are set to kick off their vermiculture activities. In the coming years, there are plans for vermiculture centres in each of the 25 woredas of the Arsi zone, paving the way for a more sustainable farming future in this area and possibly in other regions.

References

Azarmi, R., Giglou, M. T., & Taleshmikail, R. D. (2008). Influence of vermicompost on soil chemical and physical properties in tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum) field. African Journal of Biotechnology, 7(14).

Dhakal, G. (2013). Effect of vermicompost on soil properties, growth, yield and disease control of tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum L): A Review.